Difference between revisions of "History of the Sega Dreamcast/Development"

From Sega Retro

AllisonKidd (talk | contribs) |

|||

| Line 67: | Line 67: | ||

Alternatively, some suggested it was Microsoft that pushed for the NEC-backed project, as at the time, a close relationship between the two companies meant millions of NEC computers were shipping with Microsoft products as standard.{{fileref|EGM US 102.pdf|page=38}} | Alternatively, some suggested it was Microsoft that pushed for the NEC-backed project, as at the time, a close relationship between the two companies meant millions of NEC computers were shipping with Microsoft products as standard.{{fileref|EGM US 102.pdf|page=38}} | ||

| − | While both the 3Dfx and PowerVR chips marked a significant improvement over the competition in terms of performance, the decision to abandon 3Dfx was met with disappointment and in some cases resentment among sections of the gaming world, particularly in the US, as the termination of the Black Belt contract led to sizable job losses at Sega of America. In particular, the choice to go for the Katana project puzzled Electronic Arts, a long time Sega partner who had invested in the 3Dfx company. This, along with poor Saturn sales, may have attributed to why the publisher refused to back the Dreamcast in its final iteration. | + | While both the 3Dfx and PowerVR chips marked a significant improvement over the competition in terms of performance, the decision to abandon 3Dfx was met with disappointment and in some cases resentment among sections of the gaming world, particularly in the US, as the termination of the Black Belt contract led to sizable job losses at Sega of America (and at least five walk-outs in protest{{fileref|UltraGamePlayers US 103.pdf|page=23}}). In particular, the choice to go for the Katana project puzzled Electronic Arts, a long time Sega partner who had invested in the 3Dfx company. This, along with poor Saturn sales, may have attributed to why the publisher refused to back the Dreamcast in its final iteration. |

3Dfx were not pleased, believing that they were in the process of producing a chip that both met and in some cases exceeded Sega's expectations in terms of size, performance and cost. However, Sega's decision has also been attributed to 3Dfx leaking details and technical specifications of the then-secret Black Belt project when declaring their Initial Public Offering in April 1997 (though 3Dfx had blanked most of its secrets out). Either way, Sega's investment in 3Dfx allowed them to lay claim to the technology behind the Black Belt project, to avoid it being used by competitors (such as Sony, who had expressed an interest).{{fileref|EGM US 099.pdf|page=22}} | 3Dfx were not pleased, believing that they were in the process of producing a chip that both met and in some cases exceeded Sega's expectations in terms of size, performance and cost. However, Sega's decision has also been attributed to 3Dfx leaking details and technical specifications of the then-secret Black Belt project when declaring their Initial Public Offering in April 1997 (though 3Dfx had blanked most of its secrets out). Either way, Sega's investment in 3Dfx allowed them to lay claim to the technology behind the Black Belt project, to avoid it being used by competitors (such as Sony, who had expressed an interest).{{fileref|EGM US 099.pdf|page=22}} | ||

| − | In response, 3Dfx filed a $155 million USD lawsuit in September against Sega and NEC, claiming that they had been misled into believing that their technology would be used when in fact a back-room deal had been done between the two Japanese companies in the months prior to the announcement.{{intref|Press release: 1997-09-02: 3Dfx Interactive Files Lawsuit Against Sega Enterprises, Sega of America and NEC Corporation}} They also claimed that Sega deprived 3Dfx of confidential materials in regards to 3Dfx's intellectual property. The lawsuit was settled in August 1998, with Sega paying USD $10.5 million to 3Dfx. | + | In response, 3Dfx filed a $155 million USD lawsuit in September against Sega and NEC, claiming that they had been misled into believing that their technology would be used when in fact a back-room deal had been done between the two Japanese companies in the months prior to the announcement.{{intref|Press release: 1997-09-02: 3Dfx Interactive Files Lawsuit Against Sega Enterprises, Sega of America and NEC Corporation}} They also claimed that Sega deprived 3Dfx of confidential materials in regards to 3Dfx's intellectual property{{fileref|UltraGamePlayers US 103.pdf|page=19}}. The lawsuit was settled in August 1998, with Sega paying USD $10.5 million to 3Dfx. |

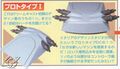

[[File:DCProto4.jpg|thumb|The Dreamcast, circa early 1998. Note the lack of logos and a rounded {{Start}} button.]] | [[File:DCProto4.jpg|thumb|The Dreamcast, circa early 1998. Note the lack of logos and a rounded {{Start}} button.]] | ||

With Katana marked as the way forward, VideoLogic revealed details on their upcoming PowerVR Series II graphics chip in early 1998,{{fileref|NextGeneration US 39.pdf|page=18}} with commentators suggesting it could achieve parity with the [[Sega Model 3]] board for roughly $99 USD (versus the Model 3's $6000 price tag at the time). | With Katana marked as the way forward, VideoLogic revealed details on their upcoming PowerVR Series II graphics chip in early 1998,{{fileref|NextGeneration US 39.pdf|page=18}} with commentators suggesting it could achieve parity with the [[Sega Model 3]] board for roughly $99 USD (versus the Model 3's $6000 price tag at the time). | ||

Revision as of 08:56, 26 December 2016

Contents

Pre-announcement

Sega Saturn

Such was the state at Sega at the time, a successor to the Sega Saturn was being considered by the firm even before the console had been released.

After a series of talks with Nintendo for a CD-based add-on for the Super Nintendo console broke down, Sony unveiled their stand-alone PlayStation system in November 1993, rattling Sega's management considerably. Sega had not seen Sony as a threat until this point, worried instead of what Nintendo may have had in-store with their presumed successor to the Super Nintendo. Ironically, Sony's 3D-focused hardware design was inspired by the success of Sega's own Virtua Fighter in the arcades, with Sonys's goal being to surpass its graphics.

When it emerged that Sony's hardware may have been more powerful than Sega's, particularly for 3D graphics, three possible options crossed CEO Hayao Nakayama's path. Either to press on with the Saturn project as is, upgrade it, or scrap it entirely in favour of another, superior console. As such, rumours of a "Saturn 2" console appeared as early as September 1994, possibly in the form of an add-on (similar to the Sega 32X) or as a replacement to the original Saturn within one or two years.

Ultimately the decision was made to enhance the Saturn,[1] and with the help of Hitachi, extra processors were added to make the console more powerful than the PlayStation. Some of the Sega Model 2's features were also added. Unfortunately, this came at a price, and the added complexities of this rushed design meant very few programmers could tap in to the Saturn's true potential.

"Saturn 2"

Though the Saturn sold fairly strongly in Japan during 1995, talks of the Saturn 2 were still on the table, as developers across the world were becoming ever more displeased with Sega's recent offering. It emerged that the Saturn 2 project was no longer in the exclusive hands of Sega - Lockheed Martin, who had assisted the company with the graphics powering the Sega Model 1 and Sega Model 2 arcade boards, were now in charge of the Saturn 2 project, with a focus primarily on graphical power.[2]

At the time, Lockheed Martin were working on their "Real3D" series of chipsets for Windows-based PCs, and the Saturn 2 was rumoured to use the R3D/100 chipset as a base for its graphics.[3] PC graphics were not yet "standardised" at this time - DirectX had yet to be invented and though Lockheed Martin were working with the now widely used OpenGL technology, there were a vast array of competing video cards on the market.

Doubts began to be cast towards the end of the year, due to Sega's increased frustrations with Lockheed Martin, who were simultaneously working on the Sega Model 3 arcade platform. The Model 3, once set for release in late 1995, wasn't due to be seen until mid-1996, causing Sega to temporarily lose its competitive edge in the arcades.

At this time, Sega partnered with the rising graphics company, NVIDIA, who based their first video card, the NV1 off the Sega Saturn hardware (even allowing for Saturn controllers to be plugged in via a second board). NVIDIA had a hard time persuading Sega that the technology was the future, however - Sega were already sceptical due to the PlayStation's early success, and even though Sega converted several Saturn games to benefit from the NV1, sales of the video card were poor. NVIDIA reportedly started to work on a successor, the NV2 but the project was shelved. Had it been finalised, the technology behind the NV2 would likely have likely replaced the R3D/100 graphics chipset for Sega's next console.

Eclipse

During late 1995, rumours began to spread of a "64-bit" add-on to the Saturn, codenamed "Eclipse"[4] - something which was publically denied by Sega.[5] Eclipse was thought to be either a stand-alone system or a unit designed to make use of the Saturn's expansion port, however the plan fared worse than the Sega 32X with third-party developers and was scrapped.

Little is known about the Eclipse project, or if it even existed past a rough concept stage.

M2 and DVD

In 1991, founder of Electronic Arts Trip Hawkins left the company to start a new venture - the 3DO Company, with the aim of breaking into the lucrative video game console market with a high-end system, the aptly named 3DO Interactive Multiplayer. 3DO Company would design the specifications, and in what was considered a novel move at the time, license out the technology to electronics manufacturers who would build the systems. The aim was to create a uniform standard similar to what is generally seen in the music and film industries, and in a sense follow traditions set up by the IBM PC and MSX in Japan.

However, when it launched in late October 1993, the 3DO was too expensive and unable to effectively compete with the giants of Sega, Nintendo and eventually Sony. By late 1994 the firm had announced an add-on to the 3DO, later to become its own separate console, with the codename "M2". For much of the mid-1990s the M2 was the subject of much discussion, thought to be a powerful device more than capable of threatening the competition.

In early 1996 the M2 was currently in the phase of being an arcade platform, being sold to Japanese electronics giant Matsushita (now trading as Panasonic). Around this time, Sega, presumably displeased with the delays of Lockheed Martin, entered discussions with the firm, potentially suggesting a plan to abandon their Model 3 platform entirely.

In February, Sega ordered some M2 development kits in a deal which would see them provide the system exclusively with games,[6] but over the weeks and months, talks broke down. Inevitably a mixture of egos and reports of poor performance[7] led to Sega abandoning the M2 project shortly afterwards,[8] and the Sega Model 3 board was finalised and put to market. The Model 3 would be Sega's last deal with Lockheed Martin - the two companies would part ways shortly afterwards, so Lockheed Martin's "Saturn 2" project was effectively put to rest.

Sega initially denied they were talking to Matsushita about the M2, but instead were exploring the possibilities behind the upcoming DVD disc standard (Matsushita being a founding member of the DVD Forum (along with Sony)). Sega were to work with the firm to utilise DVD technology in home entertainment,[9] though little appears to have come of it.

Incidentally Sega would later partner with Yamaha to create the GD-ROM standard for use in its latest console. This kept initial costs down as Sega did not have to pay royalties to the DVD Forum, although Sega would insist that DVD remained an option for the future. Matsushita would later abruptly cancel the M2 project shortly before release in mid-1997, and eventually provide the disc technology behind the Nintendo GameCube, Wii and Wii U.

"Dural" and "Black Belt"

Nintendo's new console, the Nintendo 64, was released in September 1996, and with it, the supposed world of 64-bit gaming, and while the Saturn continued to sell well in Japan, the N64 started to dramatically eat into the Saturn's market share. The PC market was also continuing to evolve, being dominated by two graphics standards - the PowerVR series by VideoLogic, and the Voodoo cards by 3Dfx. Sega chose to approach both companies in 1996, effectively starting two "Saturn 2" projects which would work in parallel until mid-1997. Now the mission was to one-up Nintendo.

Development on VideoLogic's project would occur in Japan, and was quickly given the code name "Dural" (named after a character from Sega AM2's Virtua Fighter series). In the US, 3Dfx would work on a project known as "Black Belt".[10] Shoichiro Irimajiri came to office in 1997, and having assessed the situation decided to hire Tatsuo Yamamoto, a former IBM engineer, to work on the Black Belt project. Hideki Sato, however, got wind of this idea, and joined the Dural project with his team. Though both were seprate operations, the two were following the same trends and inevitably made similar decisions, causing a great deal of confusion across the gaming press at the time.

It was Dural which made the first public move, when Hitachi, a company who had already played a role in the Sega 32X and Sega Saturn's development, announced it would be making the CPU for the Japanese machine. This turned out to be the Hitachi SH-4 processor architecture (codenamed "White Belt"), which would be used in conjunction with NEC/Videologic's upcoming PowerVR Series II (codenamed "Guppy") graphics chips in the production of their main board.

However, Western commentators typically spoke of the Black Belt project, as by 1996/1997, 3Dfx were the leaders in the PC video card market. Yamamoto and his group opted to use 3Dfx's Voodoo 2 and Voodoo Banshee graphics technology, and after initially trying RISC processors from IBM and Motorola, settled on the SH-4 as the CPU of choice as well. Sega would buy a 16% stake in 3Dfx in mid-1997,[11] presumably as a sign as commitment to the company's efforts.

From a software perspective, Sega were actively seeking partnerships in 1997, though there was still much uncertainty in regards to the details. Talks began with Microsoft for undisclosed reasons, and SegaSoft found themselves on-board with Black Belt development.

At one stage the Black Belt, was shown to a limited number of developers and was apparently very well received. Details of this Western "64-bit" machine were not hard to come by,[12] but perhaps the most important feature of the Black Belt design was its operating system, designed specifically to make the machine easy to develop for (likely moreso than the Dural project at that stage[13]).

At the time Sega's policy seemed to suggest that raw processing power wasn't as important as an easy to develop for operating system (one of the many pitfalls with the Saturn). The OS was designed to aid in quick conversions of games to and from the PC. Furthermore the Black Belt project was backed by newly recruited Sega of America COO, Bernie Stolar, who had already began to attempt to discontinue the struggling Sega Saturn in the region, even going as far to claim the system was "not our future" at E3 1997.

Sega were thought to have been showing off development hardware to prospective developers and publishers around late 1997, with a converted demo version of Scud Race.[14] Notably the Sega Saturn had built a reputation of only offering arcade conversions - with the Dural, Sega wanted a more diverse selection of games, and so despite experimenting with Scud Race, a full conversion of the title was unlikely. The upcoming Daytona USA 2: Battle on the Edge was considered a more likely candidate, but in the end this did not materialise either.

Incidentally demos concerning Scud Race have since been found on Dreamcast Dev.Boxes.

Preliminary development on the Dural platform was starting to take shape in late 1997, with Sega informing developers to use Intel Pentium II-powered computers clocked at 200MHz with PowerVR graphics cards as a foundation.[15]

One curious fact confirmed by Hideki Sato is that at some point, Sega's new console was to abandon traditional electronic heat sinks and opt for a water-cooling system in order to keep its components cool.[16]

"Katana"

In early 1998 the Dural project publically became known as "Katana",[17] at a time when Sega Saturn was on its last legs. Electronic Arts dropped its Saturn support and Western versions of X-Men vs. Street Fighter seemed increasingly unlikely - a new console was sorely needed, and Sega Europe were setting a date for 1999.[18]

Initially, Sega decided to use Yamamoto's design and suggested to 3Dfx that they would be using their hardware in the upcoming console, but a change of heart caused them to use Sato's PowerVR-based design instead.[19] There are conflicting reports claiming whether the "Katana" was more powerful than the "Black Belt" or vice versa - Sonic Team and Dreamcast developer Yuji Naka was caught in 1998 stating that ports of Sonic Adventure to the PC was impossible, because 3DFX's Voodoo cards were significantly less powerful than what was in the Katana console.[20]

Alternatively, some suggested it was Microsoft that pushed for the NEC-backed project, as at the time, a close relationship between the two companies meant millions of NEC computers were shipping with Microsoft products as standard.[21]

While both the 3Dfx and PowerVR chips marked a significant improvement over the competition in terms of performance, the decision to abandon 3Dfx was met with disappointment and in some cases resentment among sections of the gaming world, particularly in the US, as the termination of the Black Belt contract led to sizable job losses at Sega of America (and at least five walk-outs in protest[22]). In particular, the choice to go for the Katana project puzzled Electronic Arts, a long time Sega partner who had invested in the 3Dfx company. This, along with poor Saturn sales, may have attributed to why the publisher refused to back the Dreamcast in its final iteration.

3Dfx were not pleased, believing that they were in the process of producing a chip that both met and in some cases exceeded Sega's expectations in terms of size, performance and cost. However, Sega's decision has also been attributed to 3Dfx leaking details and technical specifications of the then-secret Black Belt project when declaring their Initial Public Offering in April 1997 (though 3Dfx had blanked most of its secrets out). Either way, Sega's investment in 3Dfx allowed them to lay claim to the technology behind the Black Belt project, to avoid it being used by competitors (such as Sony, who had expressed an interest).[23]

In response, 3Dfx filed a $155 million USD lawsuit in September against Sega and NEC, claiming that they had been misled into believing that their technology would be used when in fact a back-room deal had been done between the two Japanese companies in the months prior to the announcement.[24] They also claimed that Sega deprived 3Dfx of confidential materials in regards to 3Dfx's intellectual property[25]. The lawsuit was settled in August 1998, with Sega paying USD $10.5 million to 3Dfx.

With Katana marked as the way forward, VideoLogic revealed details on their upcoming PowerVR Series II graphics chip in early 1998,[26] with commentators suggesting it could achieve parity with the Sega Model 3 board for roughly $99 USD (versus the Model 3's $6000 price tag at the time).

More debatable was whether it could match 3Dfx's Voodoo 2 chipset in terms of performance, however VideoLogic's deal with NEC meant PowerVR II chips could be manufactured for half the price - key for the Katana to hit its $199.99 price target. 3Dfx, meanwhile, were a much smaller organisation with no direct access to manufacturing facilities - the proven track record of NEC (and likely its Japanese origins) likely played a part in Sega's decision to side with their neighbours.

Interestingly NEC Electronics' project manager for the PowerVR series, Charles Bellfield would join Sega of America's marketing team in July 1999.[27]

It seemed as if Microsoft no longer had a role in the console's development. However, 1998 was also the period where they announced another operating system, codenamed "Dragon" was available to Katana users - one based on its Windows CE technologies. Initially it was thought the Katana could be bridging the gap between home PCs and video game consoles, however this was revealed not to be the case. Windows CE was intended to attract developers from Windows 95/98, presenting a less daunting development environment for those who had not worked on consoles before. Sega and Microsoft had been working on refining the Dreamcast version of Windows CE for two years,[28] since before Windows CE's 1996 release.

Microsoft decided to cooperate with Sega in an attempt to promote its Windows CE operating system for video games, but Windows CE for the Dreamcast showed very limited capabilities when compared to the Dreamcast's native operating system. The libraries that Sega offered gave room for much more performance, but they were sometimes more difficult to utilize when porting over existing PC applications. Numerous Sega executives have gone on record stating that they felt the native OS was faster and more powerful, but the deal did give Microsoft the much needed knowledge for its Xbox project.

There were also troubles with Electronic Arts. Sega's financial position meant they were unable to offer the same generous offers which kept the company by their side in previous generations.

Then-CEO of EA, Larry Probst (a friend of Bernie Stolar) allegedly put forward a deal which only saw EA sports games being released on the Katana platform for five years, potentially leading to market dominance. Sega could not meet the terms of this agreement, and neither did they appear to want to - Visual Concepts was bought by Sega for USD $10 million and the widely held view was that their next NFL game (NFL 2K) would out-perform the likes of Madden 2000. Sega attempted to get a better offer for them, but EA would not budge, leading to a Dreamcast without any support from the company at all.

During the first half of 1998 several details were leaked concerning the Katana project and a similar Sega Model 3 arcade replacement, the "NAOMI project", such as the concept of memory cards with built-in screens and a built-in modem.[29] Later, talk of proprietary disc formats, NAOMI-Dural memory card relationships and the name "Dream" appearing in the system's name.[30]

Meanwhile the US launch was being slowly pushed back, starting in Christmas 1998, then moving back to March 1999, and then April 1999[31] before finally settling on September. Stolar nevertheless had big ambitions - a $100 million marketing campaign for 1999 and plans to both secure and exceed 50% of the North American video games market.[32]

By the spring of 1998 development kits had been sent to select developers, with the hardware being highly praised.[33] Many publishers signed up to the console during this period, including supposedly Electronic Arts, who had plans at this stage to bring many games to the system.[34]

Sega New Challenge Conference

On the 21st May, 1998 the Dreamcast console was shown to the world for the first time, at a Sega press event, the Sega New Challenge Conference. The intention was to release the system in Japan in November 1998. Supposedly the console was set to be revealed on the 10th, but this clashed with the announcement of Square Enix's Final Fantasy VIII.[30]

The final name was one of 5,000 ideas brought forward by branding company Interbrand.[35] Incidentally a poll conducted by Electronic Gaming Monthly in the US suggested that "Katana" was a more popular choice among its readers (37%), followed by "Dreamcast" (15%), "Dural" (14%) and "Black Belt" (4%). The remaining 30% of correspondents didn't like any of Sega's choices.[36]

Sega's tactics were unusual for Japan - the Dreamcast would be supported along with the Saturn, primarily handling 3D titles. The Saturn would do 2D, however the move to announce the Dreamcast was seen by many Japanese developers as unnecessary solely because the Saturn was holding its ground quite nicely. Sega had expected a PlayStation 2 to be released in late 1999 (it was actually early 2000) and wanted to build up a year's worth of titles in advance to stall Sony's efforts. Similarly, delays in western regions were put in place to give the console a strong launch lineup.

The internals of the Dreamcast were reportedly finalised, though a final colour had not yet been chosen, with controllers (and VMUs) available in yellow, red, blue and grey colour schemes.[37] Interestingly Sega had originally planned to distance its company name from the brand - unlike production Dreamcasts (and North American advertising), no "SEGA" lettering was to be found on the console, likely in an attempt to hide the history of the Saturn, Sega 32X and Sega Mega-CD.

At the show, several tech demos were shown, including Iri-san and Tower of Babel.[38]

E3 1998

On the 27th of May, the day prior to the start of E3 1998, Sega of America president Bernie Stolar re-announced that the Dreamcast existed and was coming to North America in the Autumn of 1999, with a planned total of 20-30 launch games.[39] No games were announced, but a couple of tech demos were shown - likely the same as a week prior, but as the gaming press were forbidden to take photos of even describe what was on show, it cannot be confirmed at this stage.

Bernie's Dreamcast had a red controller and two red VMUs. At E3 itself no Dreamcast produce was on display, just a handful of Sega Saturn titles and PC releases.

Upon its reveal in 1998, Shiny Entertainment's David Perry said it was the first time that "we will actually have an arcade machine at home" and coined the acronym "DC" to refer to the Dreamcast.[40]

Windows World Expo Tokyo 98

Between the 1st and 4th of July, 1998, Microsoft held their own Japanese expo for upcoming Windows products. Among those, the Windows CE-compatible Dreamcast, still not in its final form.

Unlike the Sega New Challenge Conference where prototype Dreamcasts were kept in glass cases or behind closed doors, here the console could be picked up and even powered on, confirming that "something" was in the shell, even though it wasn't connected to a television.

The Dreamcast on display still lacked its final shell, as evidenced by the lack of "Powered by Windows CE" text next to the controller ports. Instead, a crudely attached sticker was placed on the front of the console, with a promise that the final version would have this message printed on the shell itself.[41]

Sonic Adventure conference

On the 22nd of August, Sega held a public announcement and demonstration of the Dreamcast game Sonic Adventure at the Tokyo International Forum. While the main focus was to promote the game, the event also provided a greater insight into the capabilities of the Dreamcast console. For example, the game was running on "set 5" development hardware, which utilised "final" hardware specifications, allowing the Dreamcast to push 4 million polygons per second as opposed to the predicted 2-3 million.[42]

Sega New Challenge Conference II and Tokyo Game Show '98 Autumn

Held a few days before Tokyo Game Show '98 Autumn, Sega detailed its pricing strategy and launch titles, and tied up loose ends about what the final console package would contain.[43] A few weeks prior, Dreamcast launch date was put back five days.[44]

At TGS, Dreamcast games were made available to the public for the first time, and Sega detailed its internet strategy.

Overseas Dreamcasts

The year long gap between the Japanese and Western releases of the Dreamcast saw a few important events. It is said that Bernie Stolar went against his Japanese superiors by pricing the Dreamcast with a launch price of USD $199 (which he unveiled in a speech in early 1999, to standing ovation). Reportedly, Sega Japan wanted to price the DC at USD $249 in order to be very profitable right from the start. Stolar was fired before the Dreamcast's launch.

Issues were also raised with the PAL variant of the Dreamcast console. Its logo was feared to infringe trademarks with German publisher, Tivola. This is why PAL logos are blue.

Prototypes

The following three prototype Dreamcasts were displayed at TGS Autumn '98:

"Bread Bin" Design

Though most prototype designs were confined to the drawing board, Sega produced a few physical prototypes, the most radical is this "wedge" or "bread bin" design, unlike any video game console released before or since. This is apparently cited as being the "first" prototype, or at least, earlier than the two which follow.

It appears to sport four controller "ports" and has a lid, where presumably games would be inserted. It is grey and lacks names or logos.

"Vortex"

The second design is far more similar to the final product, though seems to be taking design lessons from the western Sega Saturn. The four controller ports are now housed at the front, similar to the Nintendo 64, and there are two buttons, one to presumably open the lid, and another to turn the unit on. It is clear from this stage that the reset button of the Saturn would not be included in the Dreamcast.

On the top is the text "Vortex" with its own logo.

"White Box"

The third iteration is far more similar to the final product. It is now white, has a power LED and a window to see the disc spinning (which would be omitted from the final design).

Others

Controller

The Dreamcast controller was derived from the Sega Saturn's 3D Control Pad. Every prototype Dreamcast controller acknowledges the need for an analogue stick.

Curiously some designs are not symmetrical, in that the left hand side is physically bigger than the right, presumably to allow to be more easily operated with one hand. This was a design trait briefly explored with the Saturn's 3D Control Pad before it was finalised.

Air NiGHTS Controller

Yuji Naka was involved in the Dreamcast project during its conception, though inevitably got caught up in Sonic Adventure's development towards the end. It is rumoured, however, that the NiGHTS into Dreams team influenced a design of the Dreamcast controller - one built like a remote and with motion sensors, almost a decade before the Wii entered the market. It was to be used in conjunction with the Air NiGHTS project.

Visual Memory Unit

Early VMU designs looked similar, if not more colorful, than the final product.

References

- ↑ File:Edge UK 105.pdf, page 49

- ↑ File:NextGeneration US 11.pdf, page 15

- ↑ File:Edge UK 025.pdf, page 6

- ↑ File:SegaPro UK 56.pdf, page 10

- ↑ File:EGM US 077.pdf, page 32

- ↑ File:Edge UK 030.pdf, page 6

- ↑ File:GamePro US 079.pdf, page 19

- ↑ File:NextGeneration US 18.pdf, page 21

- ↑ File:EGM US 081.pdf, page 20

- ↑ File:NextGeneration US 32.pdf, page 20

- ↑ File:SSM UK 21.pdf, page 10

- ↑ File:EGM US 096.pdf, page 6

- ↑ File:EGM US 098.pdf, page 23

- ↑ File:Edge UK 054.pdf, page 12

- ↑ File:NextGeneration US 36.pdf, page 24

- ↑ File:NextGeneration US 78.pdf, page 70

- ↑ File:NextGeneration US 38.pdf, page 26

- ↑ File:Edge UK 055.pdf, page 8

- ↑ File:GamePro US 110.pdf, page 72

- ↑ File:SSM UK 36.pdf, page 21

- ↑ File:EGM US 102.pdf, page 38

- ↑ File:UltraGamePlayers US 103.pdf, page 23

- ↑ File:EGM US 099.pdf, page 22

- ↑ Press release: 1997-09-02: 3Dfx Interactive Files Lawsuit Against Sega Enterprises, Sega of America and NEC Corporation

- ↑ File:UltraGamePlayers US 103.pdf, page 19

- ↑ File:NextGeneration US 39.pdf, page 18

- ↑ Press release: 1999-07-28: Sega Continues Building Executive Roster With Additions to Marketing Department

- ↑ File:GamersRepublic US 03.pdf, page 30

- ↑ File:Edge UK 058.pdf, page 11

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 File:Edge UK 059.pdf, page 9

- ↑ File:NextGeneration US 39.pdf, page 20

- ↑ File:NextGeneration US 42.pdf

- ↑ File:SSM UK 31.pdf, page 6

- ↑ File:EGM US 105.pdf, page 30

- ↑ File:Edge UK 105.pdf, page 50

- ↑ File:EGM US 112.pdf, page 24

- ↑ File:SegaMagazin DE 56.pdf, page 6

- ↑ File:GamersRepublic US 03.pdf, page 28

- ↑ File:GamePro US 110.pdf, page 30

- ↑ File:GamersRepublic US 03.pdf, page 31

- ↑ File:GamersRepublic US 04.pdf, page 12

- ↑ File:EGM US 112.pdf, page 48

- ↑ File:NextGeneration US 48.pdf, page 12

- ↑ File:NextGeneration US 48.pdf, page 14