VR-1

From Sega Retro

- For the similarly-named Japanese video game developer, see VR-1 Japan.

| |||||||||||||||||

| VR-1 | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| System(s): Large attraction | |||||||||||||||||

| Publisher: Sega | |||||||||||||||||

| Developer: Sega AM3[1], Sega AM5[2] | |||||||||||||||||

|

The VR-1 or Virtual Reality-1 is an interactive virtual reality motion simulator large attraction collaboratively developed by Sega AM3, Sega AM5, and Virtuality.[3]

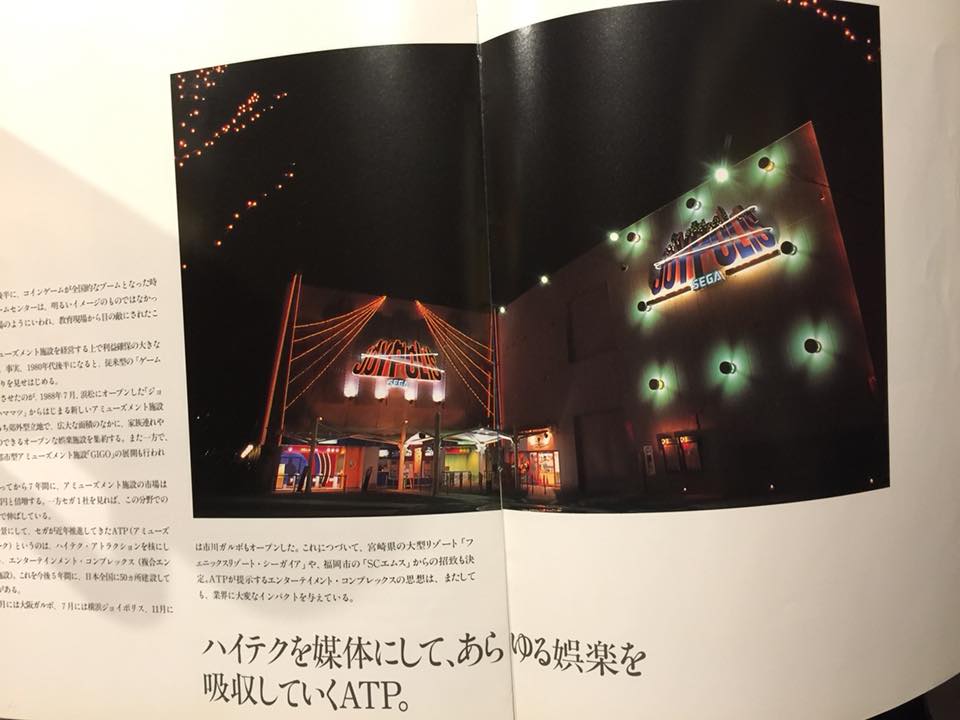

Designed to be one of the premier attractions of Sega's Amusement Theme Park venues in Japan,[4] as well as SegaWorld London and Sega World Sydney, it became one of the more well-received aspects of the venture,[3] and thanks in part to its Mega Visor Display is still considered a highly advanced example of immersive VR technology for its time.[3][5]

The hardware is unrelated to the similarly-named but separate Sega VR.[3]

Contents

Characteristics

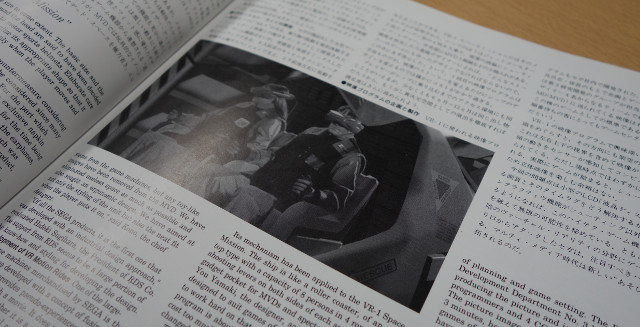

VR-1 can be defined as an interactive virtual reality amusement park attraction. While little is known about the computer hardware its experience ran on, the three main elements of the ride are its Mega Visor Display, motion simulators, and software. When unified, the three create near-total immersion for riders.

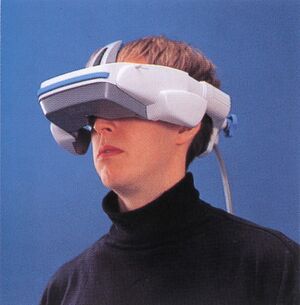

Mega Visor Display

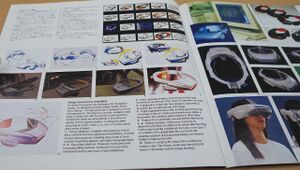

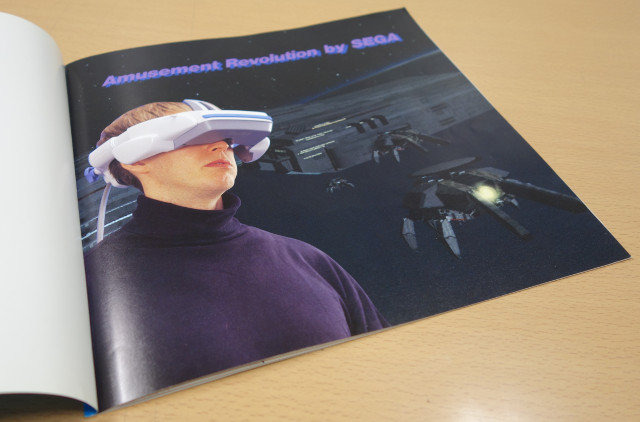

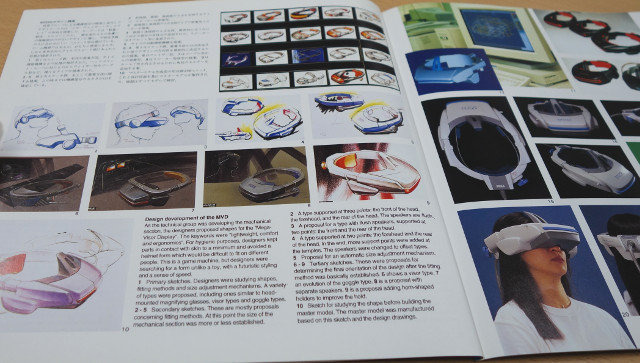

The Mega Visor Display, developed jointly by Sega AM3 and Virtuality,[3] is the central aspect of VR-1. With it, the attraction is able to successfully simulate a virtual world in a comfortable manner, earning it its namesake. When developing the headset, the key aims Virtuality and Sega followed were comfortability, light weight, and ergonomics,[5] intentionally designing it to keep body contact to a minimum, making its weight 640 grams,[3] and improving its adaptability to different head shapes through the use of adjusters. As a result, the MVD was one of the most structurally sound head-mounted displays at the time of its release.

In addition to its design advancements, the Mega Visor Display was also developed with providing a technologically superior graphical performance in mind. When originally released, the MVD could output real-time 3D graphics and pre-rendered films at a 756 x 244 pixel resolution with a 60°(H) x 46.87°(V) field of view, allowing riders to view a 360 degree landscape with the use of head tracking technology.[3] A cut-down liquid-crystal display was used to decrease the size and weight of the headset.

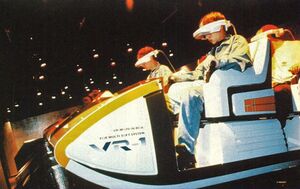

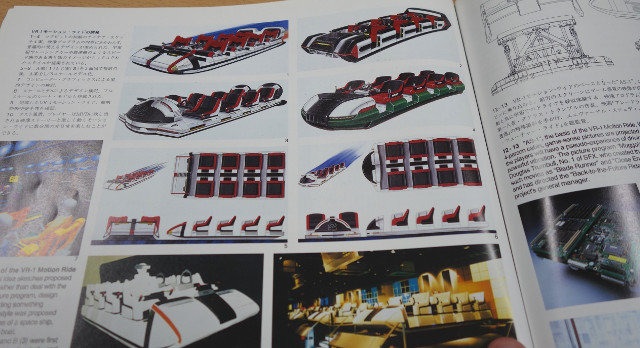

Motion simulators

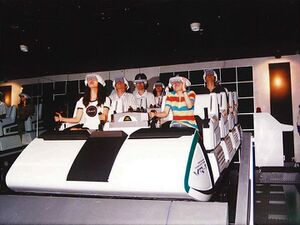

Instead of placing riders in static sit-down or stand-up pods, VR-1 uses four hydraulic motion systems to give off a stronger immersion effect to its full capacity of 32 riders. Each could seat eight people and utilised a 4 axis base, using the earlier AS-1 simulator jointly produced by Sega and Douglas Trumbull[6] as its basis.[5] Like the Mega Visor Display, numerous cosmetic appearances were designed during the development process, with an early design of one eventually seeing use on the cover of a promotional booklet for Sega's indoor theme park business.[5]

The finalised motion systems were modelled on spaceship pods, in-keeping with the attraction's space-age design motif. When running, the bases could provide 380mm vertical up/down and 34 degree left/right movement;[7] riders were provided with pre-requisite safety belts as a result of this. When not in use, the MVD headsets were stored in moulded stations situated between the seats. Alongside lighting systems and floor maps, the four pods incorporated the primary colour-coding of red, yellow, green and blue, though it is not clear if riders were accordingly divided up into teams based on this.

Software

In-keeping with Sega's company ethos of "High-Tech Entertainment" at that time, one of the main selling points of their indoor theme park locations was to provide interactive ride attractions that were not too dissimilar to coin-operated arcade games.[4] As a result, VR-1 was developed with limited but fully functional gameplay elements, instead of remaining as a purely simulation experience. The original July 1994 installation and most others made use of Space Mission, a first-person rail shooter game.[7] In it, riders attempt to reach the fictional planet "Basco", where an enemy fleet has taken off to with stolen confidential information.[7]

Shortly after the MVD headsets and sound system of the attraction were tweaked in a renewal, a software update, Planet Adventure, was released for the original Yokohama Joypolis installation in 1995,[8] and later implemented in the Fukuoka branch upon its opening during April 1996. Little is currently known about Planet Adventure, besides it involving a comical robot character, "E-2", piloting riders to an untraversed planet.[9] It is not thought to have been as widely released as the earlier Space Mission, and there is no evidence of a localisation ever being produced for overseas Sega World locations.

Ride experience

VR-1, in both its Space Mission and Planet Adventure incarnations at Yokohama Joypolis, made use of three areas. Each would approximately take three minutes to complete, making for a nine minute long attraction in total. Some installations of VR-1 are believed to have been smaller than the original version sited in Yokohama, likely not containing at least one of the former two areas before the main attraction.

MVD Trial Section

Before entering the attraction itself or joining the existing queue lines, new riders can become familiar with the Mega Visor Display headsets for the first time in the optional "MVD Trial Section", consisting of three small trial pods that can be used free of charge.

In them, a short promotional film demonstrating the MVD's intricacies is played. Dummy headsets are supplied for users to view a basic VR environment similar to the one in-game, and get to grips with the adjustment levers and switches for their own personal comfort in the attraction.

Pre-show

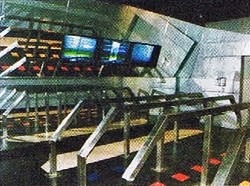

After initial admission, but before the main attraction begins, live actors/staff attendants direct riders to a pre-show viewing area much like those found in many rides found at Disneyland parks, as well as Namco's earlier Galaxian 3 attraction.

Displayed by a series of three rear projection screens as well as a lighting system, the show briefs them on the details and overall aim of the upcoming game with a short video recording. In it, the main character of the software currently ran appears, relaying the information to the awaiting attendees.

This area, like the main Space Mission game, was localised for the attraction's overseas appearances. Due to its setup, interior décor differed between locations, and a number of installations may have even used the area for queue lines.

Gameplay

Completing the pre-show, staff guide riders again towards the main attraction area, dividing them up into two to four teams if in groups larger than 8. Once all are seated, and secure with the Mega Visor Display, the interactive software and motion units are ran.

Initially viewing a pre-rendered opening cutscene that sets up the scenario, riders then are prompted to partake in a first-person rail shooter game, using the triggers situated to the left and right sides of them to dispose of enemy targets and achieve the highest score.

When the interactive software has came to its end, the attraction's on-hand staff can assist riders with removing their Mega Visor Displays and leaving. If the highest scoring patron is discerned, a "Best Gunner" badge is presented to them as a souvenir before exiting.

History

Background

During the late 1980s and early 1990s, virtual realtiy technology experienced a boom in public interest around the world for the first time.[10] After early headset iterations used by organisations such as NASA and the popularisation of the VR term itself by Jaron Lanier during the previous decade,[11] the 90s saw a glut of new commercial VR hardware released. One of the early beneficiaries of this boom was W. Industries' Virtuality Group, whose hit Virtuality 1000CS and 1000SD systems enticed arcades and out-of-home entertainment centres under the leadership of its original founder Dr. Jonathan Waldern.[10] Both were installed at a number of expositions and venues, including the popular Funland amusement centre situated in the London Trocadero and the unrelated Embracadero Center in San Fransisco.

Yet, in spite of virtual reality's acceptance among much of the public, criticism was sometimes made over the still-rudimentary graphics commercially provided to consumers at that time. Though the headsets available could simulate a virtual world, as a result of the use of hardware like the Amiga 3000, it would often be at low frame rates and resolutions, as well as using low counts of flat-shaded polygons to portray playing fields and objects.[10]

In addition, the head-mounted displays used for VR were not believed to be ergonomically ideal for prolonged use, often using large, heavy designs to accommodate the size of the technology available at that time. These raised concerns about neck strain and hygiene, among other issues. After criticisms arose and new commercial technology failed to appear quickly, initial buzz around the technology slowly died down, though consumer interest in it would remain consistent throughout much of the 1990s.[10]

At the same time of VR's surge in popularity in much of the Western world, Japanese video game and hardware developers Sega and Namco were involved in a notable rivalry over technological advancements. The companies had been competitors dating back to the earlier years of the coin-operated amusement industry,[12] however this relationship had been intensified by the rise of the Taikan motion experience games such as OutRun and Metal Hawk during the 1980s.

In what was perhaps the peak of their technological duel during 1990, Sega unveiled their rotational R360 arcade cabinet for G-LOC: Air Battle, while Namco dwarfed all previous releases in size considerably with the 28-player Galaxian 3 ride attraction, at that time only available for use as an exhibition at expositions and events, such as The International Garden and Greenery Exposition.[13] Though expensive, the two projects received overwhelmingly positive reception from gamers.

Additionally, both companies were also competing with each other by opening increasingly bigger entertainment facilities in their native countries; Namco initially had the upper hand, with the launch of Osaka's Plabo Sennichimae Tenpo venue (featuring a number of Virtuality pods and a cut-down version of Galaxian 3) in 1991,[14] and the first ever theme park opened by a video game company, Tokyo's Wonder Eggs, during the following year, where the original Galaxian 3 installation was permanently relocated and rebuilt.[15] Sega were understood to have similar plans, having already opened 150 family-oriented Sega World amusement arcades[12] and introduced a number of theme-park like attractions such as CCD Cart and Cyber Dome, but with the exception of the confirmation of plans in October 1992,[16] were largely more secretive about them. Unlike Namco, though, Sega had shown more interest in producing their own virtual reality hardware, announcing the Sega VR during 1993.[17]

Development

Whilst Sega of America undertook development on the ultimately never released Sega VR project, Sega of Japan sought outside help for their own separate virtual reality endeavours. In July 1993, W. Industries, owners of the Virtuality Group, won a £3.5 million contract[18] to collaborate with the company's amusement research and development divisions on future releases.[3][19][20] Hayao Nakayama, then president of Sega, and Virtuality founder Jonathan Waldern were photographed together, making the front page of the Game Machine coin-op trade paper and marking a significant moment for early relations between eastern and western VR developers.[21] At this stage, it was not yet specified which headset would be utilised as part of the agreement.[22]

According to initial reports, the original contract was solely for Virtuality to collaborate on a VR game for the Sega Model 1, at that time the most advanced arcade hardware on the market.[22] Because of its added prowess, it would allow the company to produce a cleaner looking and performing game experience than previous releases they were involved in. The other area where a significant improvement could be made was the ergonomic qualities of headsets; although standards were getting better in that regard, no company had produced a fully satisfactory product yet. As a result, negotiations with Sega are believed to have soon evolved to become higher-level, involving the creation of a wholly new virtual reality headset and eventually a centrepiece attraction for their planned theme parks.

Collaboration between Virtuality and Sega largely took place in the offices of the latter company's AM3 division in Japan, with two programmers (Andy Reece and Stephen Northcott) and two artists from the former company living there.[23] Whilst undertaking development on the original arcade project, the two teams shared unique optics designs and patented technology,[3] in an attempt to work towards the creation of a headset that would set a benchmark for VR moving forward. Numerous new iterations and versions were developed under tight secrecy to work out which types would work best in terms of ergonomic and graphical quality, some of which based on the advanced Visette.[3] Eventually, the designs were finalised, with the finished product christened the "Mega Visor Display".

For the creation of a larger project intended for the opening of a large flagship amusement facility in Yokohama during 1994, Sega's official theme park attraction development division, AM5, joined AM3 and Virtuality. Developers involved with VR-1 included head MVD designer Masao Yoshimoto,[5] sound composers Kazuhiko Nagai[24] and Keisuke Tsukahara,[25] and programmer Kazunari Shimamura,[26] as well as Shingo Yasumaru.[5] Much of the attraction's technology was planned to rely on pre-existing or near complete concepts, including the Mega Visor Display and 4-axis hydraulic bases used in the earlier AS-1 motion simulator,[5] however difficulties were apparently faced in synchronising the hardware and software - at full capacity, 64 sets of boards would have to be ran for 32 riders, as a result of one board being used for each eye.[5]

Release

VR-1's first permanent public installation was at Yokohama Joypolis, the first Joypolis indoor theme park, in July 1994.[27][5] Originally running the Space Mission experience, the ride was one of the premier features sited at the park on its opening day, debuting alongside two other newly-developed attractions by Sega (the non-virtual Mad Bazooka and Rail Chase: The Ride) and providing much of the basis for its main selling point of high-tech entertainment. It went on to become one of the more well received aspects of Sega's Amusement Theme Park concept, with a number of reviewers noting the Mega Visor Display's cut-down size and weight in comparison to other, more uncomfortable headsets available for public use at that time.[28][29]

In the following months, VR-1 was also installed at a number of other indoor theme park venues opened by Sega in Japan, including further Joypolis branches in Niigata[30] and Fukuoka.[30] The original Yokohama installation received an update in 1995 to run new Planet Adventure software,[8] however this would become the last support it would receive from Sega. Nonetheless, the attraction reappeared again in 1996 and 1997, when its Space Mission incarnation was localised and installed outside of Japan at SegaWorld London and Sega World Sydney. Though purportedly prone to breaking down frequently at these locations,[31] it again received praise in reviews.[32][33]

There is no known evidence of the VR-1 seeing further installations outside of the three countries it ultimately reached. After its opening in December 1995, it was purportedly going to be installed at the E-Zone Sega World arcade in Singapore alongside Mad Bazooka and Ghost Hunters to make it a venue under the Amusement Theme Park concept in March 1996,[34] however there is no evidence of this occurring. Before the creation of the GameWorks joint venture and chain of entertainment centers, Sega likely intended it to feature as a premier attraction of its planned indoor theme parks in North America.[35][36]

In spite of VR-1's relative success, as well as some of the venues supposedly exceeding visitor number and revenue expectations,[37][38][39] Sega's detour into theme park entertainment had proved to be uneconomic by the end of the 1990s, with most of their Joypolis branches and two overseas Sega World parks either closed permanently or downsized in the midst of a restructuring in the company.[3] Due to this, as well as obvious advancements in technology since its release, no VR-1 units remain in operation today, and none are currently believed to exist in any form. Virtuality's contract with Sega appears to have been terminated in 1995, with the Dennou Senki Net Merc seeing a less positive reception and limited production due to shortages of Model 1 hardware.[23]

Legacy

The VR-1, and specifically its Mega Visor Display, has been recognized as one of the most advanced pieces of virtual reality hardware of its generation.[3] The MVD subsequently inspired the designs of several other examples, ensured Sega's reputation as an early virtual reality pioneer,[5] and set a benchmark not thought to have been surpassed until the late 2010s.[3]

The MVD's life after the release of VR-1 in 1994 was short; though it was successfully used as a design motif for the Virtuaroid characters of the Virtual-On series[5] (and was rumoured to be used for Cyber Troopers Virtual-On early on in development[40]), the original arcade project that Sega and Virtuality intended to create, Dennou Senki Net Merc, was met with a less positive response, and became the final release to use the headset after being produced in very low numbers.[23]

Archival status

After the subsequent downsizing and closures of the venues that housed it during the late 1990s and early 2000s, there remain no known locations where the attraction remains in operation, and both its games are additionally unpreserved. Sega appear to hold at least one remaining Mega Visor Display headset, as well as a promotional booklet.[5]

Locations

- Yokohama Joypolis

- Ichikawa Galbo

- Yokkaichi Galbo

- Niigata Joypolis

- Fukuoka Joypolis

- SegaWorld London

- Sega World Sydney

Supported games

- Space Mission (1994)

- Planet Adventure (1995)

Patents

Videos

Footage of the attraction and Space Mission from the 01/07/1995 edition of Famitsu television series Game Catalog II

Gallery

VR-1 at Yokohama Joypolis

VR-1 at Niigata Joypolis

VR-1 at Fukuoka Joypolis

VR-1 at SegaWorld London

VR-1 at Sega World Sydney

Magazine articles

- Main article: VR-1/Magazine articles.

Promotional material

External links

- 1996 sega.jp page (archived)

- 1999 sega.jp page (archived)

References

- ↑ htt (Wayback Machine: 2004-06-10 03:24)

- ↑ File:SSM_JP_19960614_1996-09.pdf, page 144

- ↑ 3.00 3.01 3.02 3.03 3.04 3.05 3.06 3.07 3.08 3.09 3.10 3.11 3.12 https://www.vrfocus.com/2020/07/the-virtual-arena-blast-from-the-past-the-vr-1/ (Wayback Machine: 2020-08-11 13:23)

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 File:Amusement Theme Park JP Booklet.pdf

- ↑ 5.00 5.01 5.02 5.03 5.04 5.05 5.06 5.07 5.08 5.09 5.10 5.11 https://www.gamebusiness.jp/article/2016/09/14/12597.html (Wayback Machine: 2016-10-04 20:00)

- ↑ https://blog.goo.ne.jp/lemon6868/e/964683a1754808ef332712561e51b4c0 (Wayback Machine: 2021-05-07 02:05)

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 http://www.sega.co.jp/sega/atp/atc/vr_1.html (Wayback Machine: 1996-12-24 11:03)

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 http://www.sega.co.jp/sega/atp/atc/vr1planeta.html (Wayback Machine: 1999-10-11 04:00)

- ↑ Sega Magazine, "1997-03 (1997-03)" (JP; 1997-02-13), page 19

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 https://www.vrs.org.uk/dr-jonathan-walden-virtuality-new-reality-promise-two-decades-soon/ (Wayback Machine: 2020-11-28 13:13)

- ↑ https://www.newscientist.com/article/mg21829226-000-virtual-reality-meet-founding-father-jaron-lanier/ (Wayback Machine: 2021-04-27 07:39)

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 http://shmuplations.com/akiranagai/

- ↑ http://dengekionline.com/special/challenge/we/we01.html (Wayback Machine: 2019-04-24 04:17)

- ↑ Game Machine, "1991-11-15" (JP; 1991-11-15), page 14

- ↑ https://www.bandainamcoent.co.jp/corporate/history/namco/index.html (Wayback Machine: 2018-12-10 20:26)

- ↑ Game Machine, "1992-11-15" (JP; 1992-11-15), page 16

- ↑ Sega Force Mega, "August 1993" (UK; 1993-06-24), page 6

- ↑ Mega Power, "August 1993" (UK; 1993-07-29), page 8

- ↑ Sega Force Mega, "October 1993" (UK; 1993-08-19), page 7

- ↑ Mega, "September 1993" (UK; 1993-08-19), page 7

- ↑ Game Machine, "1993-08-15" (JP; 1993-08-15), page 1

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 Game Machine, "1993-08-15" (JP; 1993-08-15), page 14

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 23.2 http://www.system16.com/hardware.php?id=712 (Wayback Machine: 2021-05-06 21:27)

- ↑ https://sbtransr02.wixsite.com/kazuhiko-nagai/my-works-1 (Wayback Machine: 2021-04-10 08:56)

- ↑ https://media.vgm.io/albums/86/4768/4768-1191149488.jpg (Wayback Machine: 2021-06-03 03:08)

- ↑ File:Patent_US5662523.pdf

- ↑ Beep! MegaDrive, "September 1994" (JP; 1994-08-08), page 24

- ↑ http://www.ibiblio.org/GameBytes/issue21/misc/joypolis.html (Wayback Machine: 2016-01-15 04:09)

- ↑ https://archive.org/details/sim_japan-times_august-08-14-1994_34_32/page/n9/

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 Sega Magazine, "1997-03 (1997-03)" (JP; 1997-02-13), page 20

- ↑ https://www.independent.co.uk/travel/outings-i-have-seen-the-future-of-fun-and-it-works-sort-of-1363207.html (Wayback Machine: 2021-05-25 21:25)

- ↑ https://archive.org/details/t-3-magazine-issue-1/page/n7/mode/2up

- ↑ Computer & Video Games, "November 1996 (Freeplay #7)" (UK; 1996-10-09), page 1

- ↑ Game Machine, "1995-09-01" (JP; 1995-09-01), page 14

- ↑ Press release: 1993-07-04:Sega Takes Aim at Disney's World

- ↑ https://techmonitor.ai/technology/sega_and_matsushita_subsidiary_in_theme_park_venture (Wayback Machine: 2021-05-29 23:52)

- ↑ File:Segaworld Trocadero '96 Promo Video.mp4

- ↑ https://archive.org/details/contemporarybusi00boon/page/184

- ↑ Game Machine, "1996-06-01" (JP; 1996-06-01), page 1

- ↑ Gamest, "1995-08-15" (JP; 1995-07-15)

| Mega Visor Display | |

|---|---|

| Hardware | Mega Visor Display | VR-1 | Sega Net Merc |

| Software | Space Mission | Planet Adventure | Dennou Senki Net Merc |