Amusement Theme Park/History

From Sega Retro

- Back to: Amusement Theme Park.

Background

Following its 1965 merger with Rosen Enterprises, Sega entered the amusement operations business.[1] David Rosen had previously played an instrumental role in opening some of the country's first coin-operated arcade establishments, then known as "gun corners" and exclusively featuring shooting ranges, during the 1950s.[2] The company's original two venues opened in Hibiya, Tokyo, and Umeda, Osaka; off the back of these early facilities, often filled with used imports and in rented department store space, Sega started manufacturing its own parts, soon giving way to entire amusement machines.[1] However, as gun corners became "game corners" with the advent of more electromechanical, medal, and eventually video games, Sega lagged behind - companies like Sigma were instead among the first to open standalone venues in Japan, with its Game Fantasia Milano facility in December 1971 and several test examples during the late 1960s.[3]

Sega's position in amusement operations finally shifted in the mid 1980s, when, in the face of the fueiho law's revised restrictions and after its CSK buyout, Hayao Nakayama led the industry-wide "3K" cleanup campaign for what were becoming known in the country as "game centers".[1] The initiative, also taken on by rival companies such as Namco and Taito, set out to reduce the "kurai, kowai, and kitanai" (dark, scary and dirty) aspects of many existing locations, alongside opening new-style "amusement facilities".[1]

Fresh branded chain concepts including Hi-Tech Land Sega rolled out across urban areas in numerous prefectures, containing gendered toilets, smoking areas, and brighter lighting, in a concerted effort to appear more inviting towards all customers.[1] Some, most notably Hi-Tech Land Sega Kanda, would eventually test and make use of the Sega Game Card payment system.[4] Sega also started directly managing more of its facilities instead of renting, allowing for more long-term vacancy and flexibility.[1]

Coupled with the successful taikan games and UFO Catchers, the company's expansion paid off, contributing to its ongoing image change and social acceptance of amusement.[5] However, Sega still faced hardship in this area; going against a trend towards larger than ever venues to accommodate its increasingly complex machines, metropolitan land costs were rising in Japan due to the effects of the bubble economy.[6] As a result, urban openings had slowed, only picking up after the bubble economy later burst.

Off the back of the popular Joy Square in Hamamatsu joint venture and a proposal for large-scale expansion into cheaper suburban areas by Yoshihisa Nozaki,[6] Sega remedied this through its Sega World chain in 1989. Starting out within department stores, the brand eventually progressed to most often open on roadside business parks, beginning with O2 Park Sega World.[7] Its success led to as many as 150 Sega venues opening in one year,[1] the creation of the shortlived En-Joint concept,[8] and more large-scale locations.[9]

At the same time, Sega's rivalry with contemporaries had intensified to production of high-tech attraction-scale projects, including its own Sega Super Circuit. Namco, having previously exhibited its Galaxian 3 ride at events, were in particular inspired by the likes of Disneyland to build on success in amusement operations. The result was 1992's Wonder Eggs, the first ever amusement park operated by a video game company.[10] By now, Sega had assembled a team for interactive attraction projects using AR and VR technologies, AM5, and also achieved overseas success with the Mega Drive - coupled with their comparative lack of progress in modernizing arcades, overseas territories were now seen as a fresh target for its operations interests. Keen to continue the recent trend of Sega's rapid growth, Nakayama assessed its opportunity in revitalizing overseas amusement and driving a five-year plan to achieve ¥600 billion revenue.[11]

Development

| “ | We want to use technology to provide the quality and thrills of Disneyland in a small space. | „ |

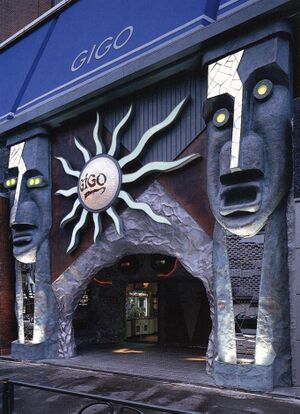

On October 14, 1992, Sega made two announcements to the amusement industry concerning its strategy for the 1990s.[13] Alongside confirmation of a tie-up with General Electric to provide technology for its amusement interests, the company affirmed its intent to enter the theme park business, beginning with a ¥2.5 billion location scheduled to open in Osaka's Asia-Pacific Trade Center during spring 1994.[14] Several new attraction projects, the pre-existent AS-1 simulator ride among them, were stated to be underway.[15] In order to prepare itself, Sega assembled the Amusement Theme Park Division with hires including Mitsuo Wachi (from Ito-Yokado) and Shinichi Tanaka (from Honda);[16] planning, design, and operation of facilities of such scale would still require considerably more know-how and workforce than before,[17] already borne out in the opening of the elaborately-themed and staffed Roppongi GiGO in September of that year.[18]

Sega's move into worldwide location-based entertainment was instrumental to its strategy for the 1990s, with Nakayama stating it to be key in his long-term aspirations to take on multimedia conglomerates like Disney.[19] Having came up through the coin-operated industry with decades of experience, location-based entertainment was most central to his interests and knowledge. At their heart, the upgraded centers would be a logical extension of Sega's previous moves in Japan, still containing various amusement machines.[20]

In drawing up plans for these, the company came up with a dedicated term and concept; Amusement Theme Park.[21] The concept defined many aspects of the venture, including what were officially deemed mid-size and large attractions, and its usage was eventually accepted by the wider amusement industry in describing similar schemes latterly created by the likes of Taito and SNK.[22] The plans emphasised the focal point of the venture, that being the high-tech equipment Sega were working with through partners like Virtuality.[23]

During 1993, further infrastructure for Sega's "ATP" advancement, stated to be aiming for 100 locations by 2000,[19] was created. Sega World Hakkeijima Carnival House opened on the site of Hakkeijima Sea Paradise in Yokohama, Japan; similar large-scale installations in the United States and United Kingdom,[24] Sega VirtuaLand and Sega World Bournemouth,[25] launched off the back of successful tests in both countries and others during the previous year.[26] All three contained early attractions developed by the company.

Whilst its esteemed AM research and development teams and developers such as Tetsuya Mizuguchi collaborated on designing the original parks and attractions, Sega kept most details on them tightly under wraps;[27] only the existence of plans for the first ATP location in Osaka, and later Yokohama, were revealed to the public.[28] Evidenced by early concept art and attraction patents, the latter was initially designed to use an outdoor location, a format which was later abandoned in favour of indoor facilities only.[15]

Critical to the ATP plans were Sega's chances at expansion in the US amusement market, which Nakayama deemed to be asleep.[29] As a result of the company's recent rise to fame in the country, talks were entered with numerous potential business partners for the move, including MCA, Time Warner, and most notably Disney.[30] Despite both companies sharing an interest in working on the cutting edge of interactive entertainment, frequent behind the scenes disagreements with then-Disney CEO Michael Eisner and other executives caused a fraught partnership;[31] both would only collaborate on exhibition space for Sega at Innoventions, ultimately delaying their ATP endeavours in the country by a number of years and allowing Disney to later imitate the concept themselves with DisneyQuest.[32] Previous public comments made by Nakayama about targeting Disney are believed to have been a particular hurdle in talks.

Active period

The first park to open under the scheme, Osaka ATC Galbo, launched on-schedule in the Asia-Pacific Trade Center during April 1994.[33] Though the facility featured all of the central ATP aspects - attractions, deluxe amusement pieces, food/retail outlets - in a 6,600m² space across two floors,[34] it was considered as the "pilot" of the concept to merely build up towards the first full-scale opening.[35] This would appear three months later during July, in the form of the flagship Yokohama Joypolis.[36] A considerably larger 8,250m² facility located on a 11,946m² plot of land in the Yamashita Park area of Yokohama,[37] the park's area encompassed multiple other food and drink outlets and allowed for more complex rides, including the debuting Rail Chase: The Ride, VR-1, and Mad Bazooka attractions.[38] The parks set the Galbo and Joypolis brands in place, the former intended for smaller installations, and the latter used for the largest flagship locations.[21]

Initial reactions to the original two locations were generally positive; Osaka ATC Galbo and Yokohama Joypolis had greeted 1,098,000 and 688,000 visitors, respectively, by the next fiscal year-end, and became the first ever amusement facilities to win the Prize for Excellence in the Service Category of the 1994 Nikkei Award for Excellent Products and Services.[39] Exceeding expectations of 1.2 million and ¥3.7 billion,[40] Yokohama Joypolis was also eventually claimed to have drawn in 1.75 million visitors and earned roughly ¥4 billion in its first year of operations.[41] However, subsequent smaller Galbo branches in Ichikawa and Yokkaichi soon fell short of their projections, and were both converted to become game centers without entry fees and attractions by 1996.[42] Niigata Joypolis, the fifth opening under the concept and second Joypolis location, similarly struggled to achieve its projected numbers after an initially successful opening in December 1995.[42]

1996 would prove to be the most active year for the concept, with three new Joypolis branches opening in Japan. Fukuoka Joypolis, originally planned to be under the abandoned Galbo brand, opened in April,[43] seeing record visitor numbers during the country's Golden Week holiday period.[44] In July, Yokohama Joypolis' flagship status was superseded by Tokyo Joypolis, more central to the capital and located in the Odaiba area.[45] At 9,600m², the facility was the largest to be opened by Sega in Japan, containing several new large attractions developed specifically for the location's larger space.[46] It attracted 10,000 visitors on opening day.[47] Shinjuku Joypolis, also located in Tokyo and initially planned alongside Fukuoka under the Galbo brand, later launched in October.[48] As flagship openings, the locations were heavily promoted in Sega publications, including Sega Magazine, and received a dedicated ATP area on the company's website.[49]

Despite the importance of overseas expansion to Nakayama, with him claiming his sites were chosen carefully out of a desire to not fail, Sega would ultimately open only two ATP sites outside of Japan. The first, SegaWorld London, launched in September 1996 within the Trocadero, Piccadilly Circus.[50] Occupying 10200m² on seven floors of the indoor complex, it would become the largest to open under the concept.[51] The second, Sega World Sydney, opened in the capital's Darling Harbour district during March 1997.[52] Both used many of the same attractions as previous Joypolis branches. Following its difficulties in partnerships with the likes of Disney, the United States instead received the separate GameWorks chain of urban entertainment centers in a joint venture with DreamWorks and Universal/MCA.[53] The centers, designed by a team of developers unrelated to Sega's, contained few mid-size attractions that originated from the ATP concept.

During the concept's active period, provisional plans for parks in France, Singapore, Hong Kong, and Taiwan were publicly acknowledged. A 1997 business tie-up with Lotte was also made for South Korea.[54]

Demise

Though Sega had made considerable investments in its ATP concept, backed up by an initially positive market reception in Japan, the start of the venture in 1994 unfortunately coincided with the company's first drop in revenue for several years.[55] Wider economic issues had hit export revenue, one of the company's strongest areas thanks to the overseas success of the Mega Drive, with subsequent drops influenced more heavily by the worsening situation surrounding the Saturn.[11] Due to the high cost involved in setting ATP sites up and operating them, little return was yet being made from even those that had fared well so far; nonetheless, their openings still contributed to rises in revenue from amusement operations for the company.[39]

Nakayama initially claimed their lack of influence on net income would be down to the base of the theme park business still being strengthened, as targets were still being met or exceeded at several openings.[29] However, expansion of the concept was still too slow for the intended goal of 100 locations, and older sites including the original Yokohama Joypolis were soon renovated by external companies in attempts to renew tapering attendance.[56] Location inconvenience, a lack of updates to game rosters, underdeveloped food and drink options, and general managerial issues have been attributed to the poor performance of some branches by the likes of former Sega director Hironao Takeda and industry specialist Kevin Williams.[57]

Nakayama's eventual resignation as president of Sega by 1998 for Shoichiro Irimajiri after his failed Bandai merger ultimately left the scheme without support from the top.[58] Though the ATP business continued during this period, with Nakayama initially still controlling Sega's AM businesses, its initial 100-strong ambitions were increasingly unlikely. Whilst domestic theme park openings slowed, the US received a different facility concept,[59] overseas Sega World branches failed to meet expectations,[60] and the new-style "nextage" Sega Arena and Club Sega chains of amusement centers appeared in Japan.[61] Those that did open experimented with the original concept; Kyoto Joypolis was smaller than previous locations and did not charge entry fees,[62] Okayama Joypolis placed more emphasis on its bowling and karaoke facilities,[63] and Umeda Joypolis, the final ATP site to open, toyed with its smaller space through urban design.[64]

Against a backdrop of continually worsening losses from the mismanagement of the Saturn and launch of the Dreamcast, Sega entered further restructuring measures under Isao Okawa, with the ATP business an early target. As part of wider attempts to liquidate its overseas amusement operations ventures that had became unprofitable,[65] SegaWorld London and Sega World Sydney were sold off during 1999 amidst management problems and significant losses estimated to be in the millions.[66] Soon after, domestic operations in Japan were also in the firing line as a wider industry decline occured; whilst Sega claimed it would focus on closing its smaller locations throughout this period,[67] many of the company's flagship Joypolis facilities ceased operations alongside them,[68] with the original Osaka ATC Galbo location also converted to become a game center in 1998 and most ATP management dismissed or transferred to other CSK subsidiaries.[69]

From 1999 onward, Sega and its remaining ATP personnel would focus more on other location-based entertainment endeavours, including the Fish "on" Chips interactive restaurant and new chain concepts.

Legacy

Though in large part a consolidated failure and by-product of the company's rivalry with its contemporaries + aspirations of becoming an empire, the Amusement Theme Park concept saw Sega exert considerable influence on location-based entertainment. The term saw wider industry acceptance and usage, inspiring other companies including SNK and Disney to make similar moves.[22] Out of the several enterprises to follow the "ATP" business model, however, Sega were able to create the most sites with 13 opened in total, despite falling short of the initial calls for 100 worldwide and 50 in Japan alone. The scheme's largest and flagship Tokyo Joypolis branch has remained open for over 25 years thus far, now a long-standing staple of the Odaiba area's tourist trade.

As its financial stability improved through the SegaSammy merger, Sega returned to the prospect of theme park entertainment in the late 2000s, opening Player's Arena in China and Sega Republic in the United Arab Emirates. Locations in other overseas territories including the UK were mooted in 2013 for a project named "Sega Infinity", but never materialised.[70] Another stab at theme parks began with the 2014 formation of Sega Live Creation, a company focused on the business; one new overseas Joypolis branch, Qingdao Joypolis, would open in July 2015.[71] The following year, 85.1% of Sega Live Creation was acquired by Hong Kong-based China Animations, with Sega retaining a 14.9% stake to provide the renamed CA Sega Joypolis with a licence for continued use of its properties.[72]

With the Okayama and Umeda branches closed during 2018, only Tokyo, Qingdao, and two new licenced Joypolis facilities in China currently remain in operation.[73] A return to other territories including the UK has again been suggested.[74]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 https://shmuplations.com/akiranagai/ (Wayback Machine: 2022-01-25 02:20)

- ↑ Next Generation, "December 1996" (US; 1996-11-19), page 10

- ↑ https://blog.goo.ne.jp/nazox2016/e/3bb6af62b8d2f2e4d97c454bbb936a14 (Wayback Machine: 2019-04-04 12:47)

- ↑ Game Machine, "1986-12-01" (JP; 1986-12-01), page 7

- ↑ https://geolog.mydns.jp/www.geocities.jp/rekisihu/tero-1.html (Wayback Machine: 2022-01-25 18:50)

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 https://blog.goo.ne.jp/lemon6868/e/d82013b20e6cca978193d54302077782 (Wayback Machine: 2021-10-10 18:50)

- ↑ http://sega.jp/location/tenpo/2008/1113_1 (Wayback Machine: 2009-08-18 08:01)

- ↑ File:SegaEnJoint JP Flyer.pdf

- ↑ Game Machine, "1990-09-01" (JP; 1990-09-01), page 12

- ↑ https://news.yahoo.co.jp/articles/f61e2782668309d70a5dbaac63b0fc0c7a2c05a9 (Wayback Machine: 2021-02-03 01:20)

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 https://mdshock.com/2021/04/14/segas-financial-troubles-an-analysis-of-export-revenue-1991-1998/ (Wayback Machine: 2021-04-14 20:32)

- ↑ M Pegler (2000). Entertainment Destinations

- ↑ Game Machine, "1992-11-15" (JP; 1992-11-15), page 1

- ↑ Famitsu, "1992-10-30" (JP; 1992-10-16), page 11

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Game Machine, "1992-11-15" (JP; 1992-11-15), page 16

- ↑ https://globis.jp/article/2305 (Wayback Machine: 2022-01-25 01:52)

- ↑ Famitsu, "1992-10-30" (JP; 1992-10-16), page 11

- ↑ Beep! MegaDrive, "November 1992" (JP; 1992-10-08), page 39

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Press release: 1993-07-04:Sega Takes Aim at Disney's World

- ↑ Press release: 1993-06:The Next Level: Sega's Plans For World Domination

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 File:Amusement Theme Park JP Booklet.pdf

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 Edge, "November 2002" (UK; 2002-10-10), page 59

- ↑ Press release: 1993-07-01: W INDUSTRIES MAKES VIRTUAL REALITY A REALITY FOR SEGA

- ↑ Sega Visions, "December/January 1993/1994" (US; 1993-xx-xx), page 12

- ↑ Mega Power, "August 1993" (UK; 1993-07-29), page 8

- ↑ Electronic Games (1992-1995), "December 1992" (US; 1992-11-10), page 11

- ↑ https://blog.goo.ne.jp/lemon6868/e/e813708f83b15c080885839bed6a7ad0 (Wayback Machine: 2021-10-10 18:53)

- ↑ Press release: 1994-02-21:Sega!

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 https://mdshock.com/2020/06/16/sega-president-hayao-nakayamas-new-year-speech-1994/ (Wayback Machine: 2020-06-17 11:44)

- ↑ https://www.gmw3.com/2017/07/the-virtual-arena-the-virtual-theme-park-part-1/ (Wayback Machine: 2022-01-24 19:10)

- ↑ https://arcadeheroes.com/2021/12/27/kevin-williams-gameworks-the-slow-collapse-of-the-dream/ (Wayback Machine: 2021-12-31 17:24)

- ↑ https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=1h6rBAAAQBAJ&pg=PA51&lpg=PA51#v=onepage&q&f=false (Wayback Machine: 2022-01-24 22:33)

- ↑ Beep! MegaDrive, "June 1994" (JP; 1994-05-07), page 110

- ↑ http://www.sega.co.jp/sega/atp/osaka/data.html (Wayback Machine: 1997-02-15 21:20)

- ↑ Game Machine, "1994-09-01" (JP; 1994-09-01), page 14

- ↑ Beep! MegaDrive, "August 1994" (JP; 1994-07-08), page 31

- ↑ http://www.sega.co.jp/sega/atp/yokohama/data.html (Wayback Machine: 1999-10-08 07:13)

- ↑ Game Machine, "1994-08-15" (JP; 1994-08-15), page 1

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 File:AnnualReport1995_English.pdf, page 3

- ↑ Press release: 1994-08-15:Shisetsu-nai Inshoku Tenpo Shirīzu 'Joiporisu' 120 Man Hito o Shūkyaku e

- ↑ https://archive.org/details/contemporarybusi00boon/page/184

- ↑ 42.0 42.1 Game Machine, "1996-03-01" (JP; 1996-03-01), page 2

- ↑ Sega Saturn Magazine, "1996-08 (1996-05-10,24)" (JP; 1996-04-26), page 43

- ↑ Game Machine, "1996-06-01" (JP; 1996-06-01), page 1

- ↑ Sega Saturn Magazine, "1996-13 (1996-08-09)" (JP; 1996-07-26), page 43

- ↑ Game Machine, "1996-08-15" (JP; 1996-08-15), page 1

- ↑ http://edition.cnn.com/TECH/9607/17/japan.joypolis/ (Wayback Machine: 2021-06-17 16:12)

- ↑ Sega Saturn Magazine, "1996-17 (1996-10-11)" (JP; 1996-09-27), page 30

- ↑ http://www.sega.co.jp/sega/atp/ (Wayback Machine: 1996-12-24 06:42)

- ↑ Sega Saturn Magazine, "1996-17 (1996-10-11)" (JP; 1996-09-27), page 1

- ↑ Press release: 1996-09-12: INTERNATIONAL MANAGER : Sega Tests the Theme-Park Route

- ↑ File:TheSydneyMorningHerald AU 1997-03-19; Page 4.png

- ↑ Game Machine, "1996-05-01" (JP; 1996-05-01), page 14

- ↑ https://www.mk.co.kr/news/home/view/1997/07/40627/ (Wayback Machine: 2022-01-24 21:57)

- ↑ Game Machine, "1994-07-01" (JP; 1994-07-01), page 14

- ↑ http://www.sega.co.jp/sega/atp/news/news994/jpnews990725.html (Wayback Machine: 2000-04-10 21:21)

- ↑ https://www.gmw3.com/2020/07/the-virtual-arena-blast-from-the-past-the-vr-1/ (Wayback Machine: 2022-01-24 17:57)

- ↑ Next Generation, "March 1998" (US; 1998-02-17), page 20

- ↑ https://www.nytimes.com/1996/03/14/business/venture-plans-sega-arcades.html (Wayback Machine: 2018-01-28 11:42)

- ↑ http://letslookagain.com/2014/01/segaworld/ (Wayback Machine: 2017-04-01 03:17)

- ↑ Sega Magazine, "1997-04 (1997-04)" (JP; 1997-03-13), page 26

- ↑ Sega Saturn Magazine, "1997-34 (1997-10-03,10)" (JP; 1997-09-19), page 11

- ↑ Press release: 1998-08-27: Okayama Joypolis Open no Oshirase

- ↑ Press release: 1998-09-24: Osaka ni Umeda Joypolis Toujou

- ↑ File:AnnualReport1999_English.pdf, page 16

- ↑ https://onitama.tv/gamemachine/pdf/19991015p.pdf

- ↑ File:AnnualReport2000_English.pdf, page 14

- ↑ Sega Saturn Magazine, "1997-34 (1997-10-03,10)" (JP; 1997-09-19), page 18

- ↑ http://www.gnr.co.jp/index_en.html (Wayback Machine: 2020-02-12 15:10)

- ↑ http://www.arcadebelgium.be/ab.php?l=en&r=art&p=repeag2013 (Wayback Machine: 2013-11-01 14:00)

- ↑ https://sega.jp/topics/150703_1/ (Wayback Machine: 2015-07-14 01:36)

- ↑ https://www.nikkei.com/article/DGXLASDZ31H5F_R31C16A0000000/ (Wayback Machine: 2016-10-31 05:27)

- ↑ http://www.casegajp.com/en/facility/ (Wayback Machine: 2022-01-14 22:44)

- ↑ https://www.videogameschronicle.com/news/sega-joypolis-theme-parks-could-be-coming-to-the-uk-and-us/ (Wayback Machine: 2021-06-01 11:58)