Difference between revisions of "Duck Hunt"

From Sega Retro

m |

|||

| Line 9: | Line 9: | ||

| em_date_jp=1968{{ref|https://web.archive.org/web/20230821093301/http://thetastates.com/eremeka/1969prior.html}} | | em_date_jp=1968{{ref|https://web.archive.org/web/20230821093301/http://thetastates.com/eremeka/1969prior.html}} | ||

| em_date_us=1968-12{{ref|1=[https://books.google.com/books?id=b0UEAAAAMBAJ&pg=PA33 ''Billboard'' (December 28, 1968), page 33]}} | | em_date_us=1968-12{{ref|1=[https://books.google.com/books?id=b0UEAAAAMBAJ&pg=PA33 ''Billboard'' (December 28, 1968), page 33]}} | ||

| + | | em_rrp_us=425{{fileref|CashBox US 1970-11-21.pdf|page=57}} | ||

}} | }} | ||

}} | }} | ||

Revision as of 05:26, 22 November 2023

| |||||||||||||

| Duck Hunt | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| System(s): Electro-mechanical arcade | |||||||||||||

| Publisher: Sega | |||||||||||||

| Developer: Sega | |||||||||||||

| Genre: Shoot-'em-Up | |||||||||||||

| Number of players: 1 | |||||||||||||

|

This short article is in need of work. You can help Sega Retro by adding to it.

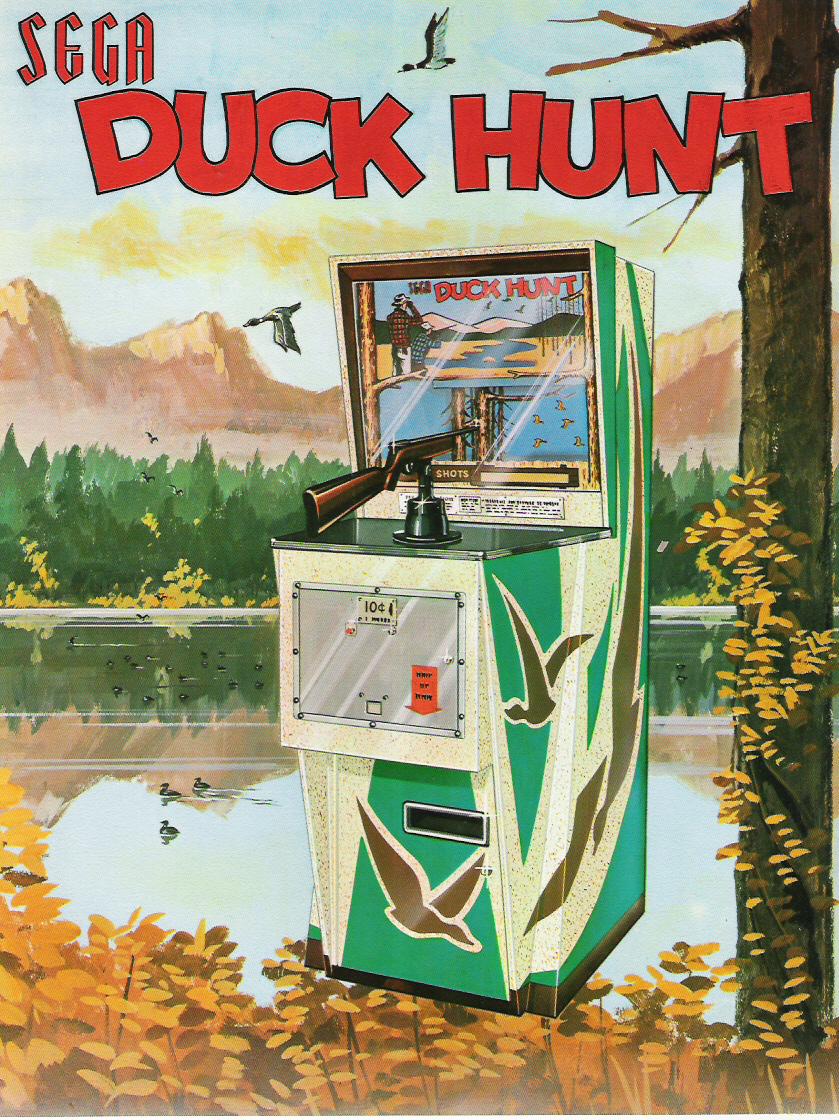

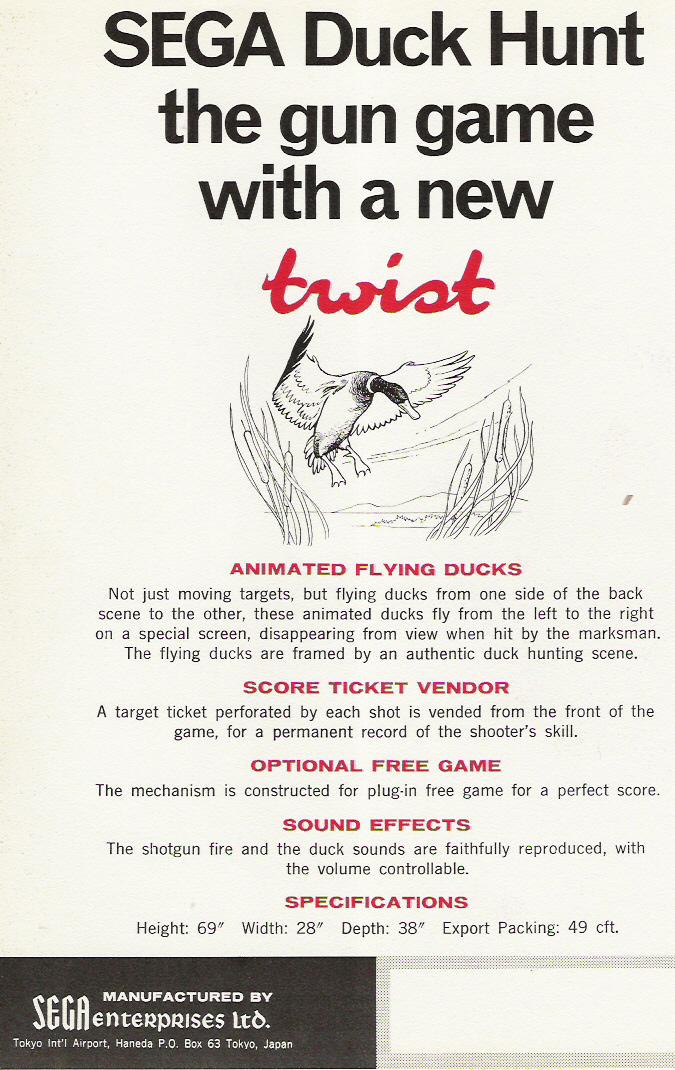

Duck Hunt, sometimes advertised under the name Duck Shoot[4], is a 1968 electro-mechanical arcade shooter game produced by Sega. A 25-cent video projection game, it features 10 animated ducks flying on a screen from left to right which disappear when shot with the attached shotgun controller.

The player receives ten shots, and the shot ducks are framed in a duck hunting score. Shooting the shot gun and hitting a duck produces a sound effect. The game dispenses a perforated computer card-style ticket showing shooting accuracy and score when game is finished which could be used for prizes or as a permanent record of the player's score. Additionally, the game could be set to give a free game for a perfect score.

Contents

Overview

It resembles a first-person light-gun shooter video game, but is in fact a video projection electro-mechanical (EM) game, using rear image projection in a manner similar to a zoetrope to produce moving animations on a screen.

This was the first electronic arcade game with animated targets displayed on a screen, in contrast to earlier EM arcade games that displayed actual physical static targets. This gave Duck Hunt the appearance of a video game, several years before the first true video games arrived in the arcades (Computer Space and Pong). Duck Hunt thus anticipated the kind of light-gun shooter video games that would later appear in the 1970s, and was the first electronic arcade game to display a first-person perspective on a screen. Duck Hunt was later updated by Midway and re-released in January 1973.

Purchase of a Duck Hunt machine comes with one roll of 3,000 paper cards. Replacement rolls could be acquired from Sega Enterprises for ¥3,000 each.[4]

Specifications

Dimensions

History

Background

In the late 1960s, Japanese companies Kasco (Kansei Seiki Seisakusho Co.) and Sega introduced a new type of electro-mechanical game, video projection games. They looked and played like later arcade video games, but relied on electro-mechanical components to produce sounds and images rather than a CRT display. They used rear video image projection to display moving animations on a video screen.[5][6][7] Video projection games became common in arcades of the 1970s. They combined electro-mechanical and video elements, laying the foundations for arcade video games, which adapted cabinet designs and gameplay mechanics from earlier video projection games.[7] They also ocassionally used solid-state electronics for sounds (like Grand Prix, Missile and Night Rider).

Legacy

After Duck Hunt, Sega produced several more electro-mechanical arcade games based on similar technology, using rear image projection to produce moving animations on a screen. In 1969, Sega released the EM games Grand Prix, a first-person driving/racing game like Kasco's Indy 500 that projects a forward-scrolling road on a screen, and Missile, a first-person vehicle combat simulation that had a moving film strip project targets on screen and a dual-control scheme where two directional buttons move the player tank and a two-way joystick with a fire button shoots and steers missiles onto oncoming planes, which explode when hit; in 1970, Missile was released in North America as S.A.M.I. Sega's Jet Rocket in 1970 was the earliest first-person shooter and combat flight simulator game, with cockpit controls that could move the player aircraft around a landscape displayed on screen and shoot missiles onto targets that explode when hit. In 1972, Sega released Killer Shark, a first-person light gun game known for appearing in the 1975 film Jaws.

The game also may have influenced Nintendo's light-gun shooters. In 1974, Nintendo's arcade light gun shooter Wild Gunman was a video projection EM game that used similar technology, but improved on it by using full-motion video projection to display live-action cowboy opponents on screen. In 1984, Nintendo released their own video game called Duck Hunt, which played similarly to Sega's 1969 electro-mechanical arcade game of the same name.

Duck Hunt may have also influenced Kasco's 1975 arcade game Gun Smoke, a light gun shooter that was the first holographic 3-D game. It was a hit in Japan, selling 6,000 cabinets there, but only 750 cabinets were sold in the US.[8] It was followed by two more holographic Kasco gun games, Samurai and Bank Robber, released between 1975 and 1977, as well as a 1976 Midway clone, Top Gun. The first holographic video games would later be Sega's Time Traveler (1991) and Holosseum (1992).[9]

Promotional material

Photo gallery

References

- ↑ http://thetastates.com/eremeka/1969prior.html (Wayback Machine: 2023-08-21 09:33)

- ↑ File:CashBox US 1970-11-21.pdf, page 57

- ↑ Billboard (December 28, 1968), page 33

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 1977 Sega Price List, page 6

- ↑ Killer Shark: The Undersea Horror Arcade Game from Jaws, D.S. Cohen, About.com

- ↑ Kasco and the Electro-Mechanical Golden Age (Interview), Classic Videogame Station ODYSSEY, 2001

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Once Upon a Time on the Screen: Wild West in Computer and Video Games, Academia

- ↑ Gun Smoke

- ↑ Holograms: A Cultural History, page 179