Difference between revisions of "Craig Stitt"

From Sega Retro

m |

|||

| (9 intermediate revisions by 3 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{PersonBob | {{PersonBob | ||

| − | | image= | + | | image=CraigStitt.jpg |

| − | | birthplace= | + | | birthplace=[[wikipedia:United States|United States]] |

| dob= | | dob= | ||

| dod= | | dod= | ||

| − | | company=[[Sega Technical Institute]] | + | | employment={{Employment |

| − | | | + | | company=[[Sega of America]]{{ref|https://www.linkedin.com/in/craig-stitt-5257bb97/}} |

| − | | | + | | divisions=[[Sega Technical Institute]] |

| + | | start=1990{{ref|https://www.linkedin.com/in/craig-stitt-5257bb97/}} | ||

| + | | end=1995{{ref|https://www.linkedin.com/in/craig-stitt-5257bb97/}} | ||

}} | }} | ||

| − | {{ | + | {{Employment |

| + | | company=Insomniac Games{{ref|https://www.linkedin.com/in/craig-stitt-5257bb97/}} | ||

| + | | notsega=yes | ||

| + | | start=1995{{ref|https://www.linkedin.com/in/craig-stitt-5257bb97/}} | ||

| + | | end=2005{{ref|https://www.linkedin.com/in/craig-stitt-5257bb97/}} | ||

| + | }} | ||

| + | | role=Artist{{ref|https://www.linkedin.com/in/craig-stitt-5257bb97/}} | ||

| + | | education=[[wikipedia:San Jose State University|San Jose State University]] (19xx-19xx; BA Art Education){{ref|https://www.linkedin.com/in/craig-stitt-5257bb97/}} | ||

| + | }} | ||

| + | {{stub}}'''{{PAGENAME}}''' is an American art director and former [[Sega Technical Institute]] artist, known for his work on a number of the studio's Western-developed [[Mega Drive]] titles.{{ref|https://www.linkedin.com/in/craig-stitt-5257bb97/}} Hired in 1990 as one of the studio's earliest artists, Stitt created artwork for games like ''[[Kid Chameleon]]'', ''[[Sonic the Hedgehog 2 (16-bit)|Sonic the Hedgehog 2]]'', and ''[[Astropede]]'', among others, and remained with Sega until his departure for [[wikipedia:Insomniac Games|Insomniac Games]] in 1995.{{intref|Interview: Craig Stitt (2001-01-23) by ICEknight}}{{ref|https://www.linkedin.com/in/craig-stitt-5257bb97/}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Career== | ||

| + | From an early age, {{PAGENAME}} spent much of his youth in arcades back in the 1970s, placing games like ''Space Invader'', ''Asteroids'', and ''BattleZone'', alongside tabletop games like ''Dungeons & Dragons'' and ''Risk'', but never got around to purchasing a home video game system of his own. He had also accumulated a good deal of experience in the creation of computer graphics at a small company called Genigraphics, but was somewhat frustrated by the lack of engaging projects.{{intref|Interview: Craig Stitt (2020-08-29) by Damiano Gerli}} Sometime in 1990, Stitt came across an ad in the newspaper that read "WANTED: Video game designers and artists, no experience necessary." After getting called back by Sega, he borrowed an [[NES]] from a friend and spent the next few days familiarizing himself with as many games as possible. Thankfully, he was officially hired by [[Mark Cerny]]{{intref|Interview: Craig Stitt (2020-08-29) by Damiano Gerli}} as a game artist at [[Sega Technical Institute]] shortly after.{{intref|Interview: Craig Stitt (2001-01-23) by ICEknight}} His very first game would be the 1992 action platformer ''[[Kid Chameleon]]''.{{ref|1=https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UOlHbBTF8eI}} During his time with the company, he had a hand in creating artwork for a number of the studio's projects, including unreleased [[Mega Drive]] titles like ''[[Dark Empires]]'', ''[[Jester]]'', and ''[[Astropede]]'', among others. He also did some minor work for ''[[Comix Zone]]'' and ''[[Kid Chameleon]]''.{{intref|Interview: Craig Stitt (2001-01-23) by ICEknight}} | ||

| + | |||

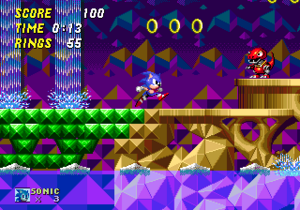

| + | [[File:Hiddenpalaces2.png|thumb|right|Stitt was the primary artist for ''[[Sonic the Hedgehog 2 (16-bit)|Sonic the Hedgehog 2]]'''s infamous [[sonic:Hidden Palace Zone|Hidden Palace Zone]].]] | ||

| + | Stitt's most well-known contribution to video gaming was his work on ''[[Sonic the Hedgehog 2 (16-bit)|Sonic the Hedgehog 2]]''. Acting as a level artist, he created artwork for a number of the game's Zones. While he was not directly responsible for designing any Zone layouts, he did occasionally have a hand in creative brainstorming in the design process. Stitt was provided with a [[Digitizer]] for creating his pixel art and a rudimentary paper map of a Zone layout, and once he created about a couple hundred tiles on the hardware, he would begin implementing them in the actual game. He recalls that some of his work was not included in the final release, including art of a clown/rollercoaster-themed Zone, alongside the famous [[sonic:Hidden Palace Zone|Hidden Palace Zone]], stating "if art had to get cut out it always seemed to be the American's on the team whos art got cut."{{intref|Interview: Craig Stitt (2001-01-23) by ICEknight}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | Following ''Sonic 2'', Stitt went about designing a mascot-platformer of his very own. Titled ''[[Astropede]]'', it spent about 14 months in development before being permanently put "on hold". While described by Stitt as a "solid game", he feels it would have performed well if it had been better managed and actually released. Reportedly, ''Astropede'' was the only reason Stitt was remaining at [[Sega of America]], and following its shelving in 1994, he was prompted to leave the company only one year later.{{intref|Interview: Craig Stitt (2001-01-23) by ICEknight}} Following his departure from the company, Stitt accepted a position as Art Director at the [[wikipedia:Burbank, California|Burbank, California]]-based developer [[wikipedia:Insomniac Games|Insomniac Games]] later that year.{{ref|https://www.linkedin.com/in/craig-stitt-5257bb97/}} | ||

==Production history== | ==Production history== | ||

| − | + | {{ProductionHistory|{{PAGENAME}}}} | |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ==Interviews== | |

| − | + | {{InterviewList|{{PAGENAME}}}} | |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ==External links== | |

| − | + | *[https://www.linkedin.com/in/craig-stitt-5257bb97/ {{PAGENAME}}] at [https://www.linkedin.com/ LinkedIn] | |

| − | * | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

==References== | ==References== | ||

<references /> | <references /> | ||

Latest revision as of 06:52, 9 November 2023

|

| Craig Stitt |

|---|

| Place of birth: United States |

| Employment history:

Divisions:

|

| Role(s): Artist[1] |

| Education: San Jose State University (19xx-19xx; BA Art Education)[1] |

This short article is in need of work. You can help Sega Retro by adding to it.

Craig Stitt is an American art director and former Sega Technical Institute artist, known for his work on a number of the studio's Western-developed Mega Drive titles.[1] Hired in 1990 as one of the studio's earliest artists, Stitt created artwork for games like Kid Chameleon, Sonic the Hedgehog 2, and Astropede, among others, and remained with Sega until his departure for Insomniac Games in 1995.[2][1]

Career

From an early age, Craig Stitt spent much of his youth in arcades back in the 1970s, placing games like Space Invader, Asteroids, and BattleZone, alongside tabletop games like Dungeons & Dragons and Risk, but never got around to purchasing a home video game system of his own. He had also accumulated a good deal of experience in the creation of computer graphics at a small company called Genigraphics, but was somewhat frustrated by the lack of engaging projects.[3] Sometime in 1990, Stitt came across an ad in the newspaper that read "WANTED: Video game designers and artists, no experience necessary." After getting called back by Sega, he borrowed an NES from a friend and spent the next few days familiarizing himself with as many games as possible. Thankfully, he was officially hired by Mark Cerny[3] as a game artist at Sega Technical Institute shortly after.[2] His very first game would be the 1992 action platformer Kid Chameleon.[4] During his time with the company, he had a hand in creating artwork for a number of the studio's projects, including unreleased Mega Drive titles like Dark Empires, Jester, and Astropede, among others. He also did some minor work for Comix Zone and Kid Chameleon.[2]

Stitt's most well-known contribution to video gaming was his work on Sonic the Hedgehog 2. Acting as a level artist, he created artwork for a number of the game's Zones. While he was not directly responsible for designing any Zone layouts, he did occasionally have a hand in creative brainstorming in the design process. Stitt was provided with a Digitizer for creating his pixel art and a rudimentary paper map of a Zone layout, and once he created about a couple hundred tiles on the hardware, he would begin implementing them in the actual game. He recalls that some of his work was not included in the final release, including art of a clown/rollercoaster-themed Zone, alongside the famous Hidden Palace Zone, stating "if art had to get cut out it always seemed to be the American's on the team whos art got cut."[2]

Following Sonic 2, Stitt went about designing a mascot-platformer of his very own. Titled Astropede, it spent about 14 months in development before being permanently put "on hold". While described by Stitt as a "solid game", he feels it would have performed well if it had been better managed and actually released. Reportedly, Astropede was the only reason Stitt was remaining at Sega of America, and following its shelving in 1994, he was prompted to leave the company only one year later.[2] Following his departure from the company, Stitt accepted a position as Art Director at the Burbank, California-based developer Insomniac Games later that year.[1]

Production history

- Kid Chameleon (Mega Drive; 1992) — Art[5]

- Sonic the Hedgehog 2 (Mega Drive; 1992) — Zone Artists[6]

- Sonic the Hedgehog Spinball (Mega Drive; 1993) — Art[7]

- Comix Zone (Mega Drive; 1995) — Animation[8]

- The Ooze (Mega Drive; 1995) — Artists[9]

- Comix Zone (Windows PC; 1995) — Animation[8]

- Astropede (Mega Drive; unreleased) — Lead Designer

- Astropede (Mega Drive; unreleased) — Lead Artist

- Dark Empires (Mega Drive; unreleased) — Artist

- Jester (Mega Drive; unreleased) — Artists

- SpellCaster (Mega Drive; unreleased) — Designer

- Treasure Tails (Mega Drive; unreleased) — Artist

Interviews

- Interview: Craig Stitt (2001-01-23) by ICEknight

- Interview: Craig Stitt (2020-08-29) by Damiano Gerli

External links

References

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 https://www.linkedin.com/in/craig-stitt-5257bb97/

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 Interview: Craig Stitt (2001-01-23) by ICEknight

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Interview: Craig Stitt (2020-08-29) by Damiano Gerli

- ↑ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UOlHbBTF8eI

- ↑ File:Kid Chameleon MD credits.pdf

- ↑ File:Sonic the Hedgehog 2 MD credits.pdf

- ↑ File:Sonic Spinball MD credits.pdf

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 File:Comix Zone MD credits.pdf

- ↑ File:Ooze MD credits.pdf