Vectorman/Development

From Sega Retro

- Back to: Vectorman.

As one of the Mega Drive's most technically impressive Western-designed video games, the development of Vectorman was one of BlueSky Software's greatest achievements on Sega's 16-bit platform, setting a new precedent for technical accomplishments and inspiring a number of fellow developers to really begin pushing the hardware's limits.[2][3]

Development

After witnessing the 1989 demo Megademo by the demoscene group RSI - one of many demos featuring "vector balls", in which plain spherical sprites are animated to give the appearance of three-dimensional depth - BlueSky Software programmer Karl Robillard was inspired to get the same rendering technology running on Sega's then relatively-new Genesis hardware. Robillard soon programmed his own "vector balls" engine (eventually named VAT - Vectorman Animation Tool), and along with fellow programmer Rich Karpp was able to create an impressive Genesis implementation of the technology, all running at a surprisingly smooth framerate. As the studio was concluding development on Jurassic Park in mid 1993,[4] some rudimentary animations were created as proof of concept build, which according to Marty Davis, was technically impressive but difficult to integrate with actual gameplay.

| “ | Originally Karl and some of the others had devised a system to do actual 3D on the Sega Genesis, and they started with an animation of some 3D balls. This was actual 3D computing — on a Genesis. I saw the demo in Karl’s office back in ’93. They quickly realized there wasn’t much to be done with the original 3D ball tech because you couldn’t get it to run in a gameplay situation.”, adding “This was all before the ‘Ballz’ game came out. That game sorta proved the unworkability of the concept.

|

„ |

BlueSky's art director, Dana Christianson, overheard some of the team discussing possibilities for using the technology for different gameplay mechanics, and soon called for a meeting with BlueSky designers Mark Lorenzen and Jason Weesner. The latter formally proposed turning the popular demo into a video game, and management approved. The team was soon joined by artist and designer Mark Lorenzen, who along with Karpp convinced BlueSky's already-impressed management to show one of their early demos to Sega of America. Sega was just as impressed, and greenlit Vectorman for proper development. At the time, Nintendo's upcoming Donkey Kong Country was being heavily marketed, with its pre-rendered graphics taking center stage; particularly, the advertisements stated that such technology and animation were impossible on the Mega Drive. Sega of America saw Vectorman as one of their best opportunities to counter Donkey Kong Country's hype with an impressive technology of their own.

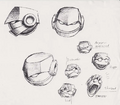

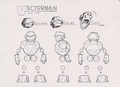

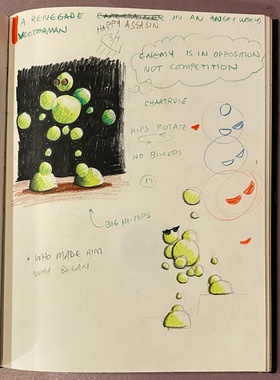

Electronic musician Jon Holland was soon brought onboard, and he, Lorezen, Karpp, and Weesner spent the next few weeks formulating ideas for what would eventually become Vectorman. Between listening to music, watching anime, and playing imported Japanese games for inspiration, these creative meetings were where much of the gameplay was conceptualized: a side-scrolling run-and-gun with elements of action platformers. However, the game's style had still yet to be finalized. According to Weesner, "Mark, Rich, and I wanted something edgy, contemporary, and geared towards a hipper audience than previous BlueSky games."[1] Vectorman's protagonist began as a simple cartoon-like character named Shakespeare, boasting large eyes and a big nose, although this design was quickly rejected for being "too cute". Still, Lorenzen was beginning to become acquainted with delivering human expressiveness through the game's unique sphere-rendering technology (particularly in terms of shading individual spheres to better convey depth and realism), and ended up filling up two development sketchbooks with concept artwork and preliminary sketches.

Vectorman was designed around advanced graphical effects from the very beginning, and much of the game's development reflected the team's attempt to fully use its unique technology to the fullest. Enemies and bosses were created with sphere-based designs, and stage layouts were conceptualized which would further showcase the team's programming skill. Lorenzen worked with fellow BlueSky artist Rick Schmitz, who provided a few key concept sketches for the protagonist's expressions and would end up finalizing the character's design as the titular VectorMan. Another artist, Ellis Goodson, also did further concept artwork for the character. Marty Davis served VectorMan's animator, and as the developer who directly developed elements like ball spacing and animation speeds, refined most of the character's animations through Karl Robillard's VAT. Per Goodson, “the 3D aspects of Vectorman got everyone excited. That illusion of depth was what was going to get reaction from the players.”[1]

In early January 1995, Marty Davis created a rough journal of the game's stage IDs, enemy names, a development timeline, and directions to other team members. Davis describes development then as being four weeks behind schedule, with an estimated four months until the game was to be shipped. That expected ship date of around May would be pushed back almost half a year to October. It was during this time that Vectorman as we know it today began to come into shape, with a substantial amount of the game's design and development finalized. Much of the developers attributed their sheer passion as one of the driving forces behind seeing its development cycle through - and delivering a fun, innovative game that could serve as a "benchmark" for the console's performance. Davis says "the super-sophisticated tech allowed this — running at 60 fps, super-responsive character control with graphics that matched. It was the gameplay that was always the focus in developing the game. People mention Donkey Kong Country as the benchmark, but I remember Gunstar being a much bigger benchmark than DKC. There were plenty of situations where we dropped cool graphics in favor of performance."[1]

| “ | We had learned from Shiny Entertainment and other competitors how vertical line blending was more preferable on the TV than straight dithering. That is why everything looked weird on the PC. Those vertical lines blend automatically on the TV. While we were trying to prevent dizzying ‘Moiré effects’, in this case it helped. Because of this I was able to solve the Aurora EFX problem by building a ‘fake effect’ by adding two layers of bar patterns, one using the parallax scrolling features of the Genesis. The parallax layer operated behind black bars of the top and used hard coded distortion and color gradient patterns. The best news is that I could control this sequencing myself on our Tile Editing tool (TED) Emulator. Being able to see and adjust the effect myself was half the battle. As a result, I was able to deliver something close to Mark’s vision, even if I did it with duct tape. | „ |

A number of BlueSky artists have stated that the process of creating Vectorman's tile-based artwork was unexpectedly difficult for the team; "it was such a challenge to make titles not look repeatable. It was like putting together a puzzle",[1] recalls background artist Amber Long. According to Jeff Remmer, Lorenzen had the idea to build the game in a tile-based fashion to ensure tiles were reusable in multiple levels, and tasked Remmer with creating pixel artwork that would implement such a fashion. The first level produced with these tiles was the unused stage Wicker Rocket. While ultimately scrapped, the stage would help the team understand the challenges in creating tile-based artwork. Lorenzen remembers the stage well: "There was going to be a level where Vectorman found himself aboard a rocket made of wicker and sliding down a launch track. It’s like the rocket in George Will’s ‘When Worlds Collide’. While it looked cool and we had the look of it and all the tech well under way, we cut it because we could not make it fun."[1]

| “ | Mark had the idea that the background artists could re-use tiles on other levels if they were created with a dual purpose in mind. I was tasked with trying his experiment on the Wicker Rocket level. Now the Wicker Rocket was already a very specific and wacky creation to begin with and trying to create other art out of it just wasn’t going to happen. I worked on it for a few weeks and the level looked and played pretty good but it was eventually scrapped. Now trying out new ideas was a big part of game development at BlueSky, but I must have pulled out some of my hair building the Wicker Rocket. | „ |

After spending some time creating pixel artwork, Remmer was assigned to a task he was more comfortable with: oil painting. Remmer's paintings were then scanned by fellow BlueSky developer Geoff Knobel: "Geoff was the first person I knew who used a scanner to create final art for games. It took a lot of effort to simplify all the color variation without losing the image’s clarity" remembers Remmer.[1] These oil paintings were then digitized and used on the final game's stage splash screens. Additionally, some of the game's artwork are actually digitized photographs - the first stage's animated flags were digitized from a video of real flats fluttering atop BlueSky's offices, shot on a particularly windy day by Mark Lorenzen himself.[1]

Musician Jon Holland provided Vectorman with its distinct club-inspired soundtrack. An electronic music specialist and DJ, he was hired because BlueSky Software's regular sound composer, Sam Powell, was working on other company projects and was unavailable. Holland had been cold-calling BlueSky for some time, and had even left a demo tape of his musical style with Powell. His persistence paid off, and a few months after dropping off the cassette he formally joined the game's development in its pre-production face. As Holland had no experience with programming music for video games, he had to rely on teaching himself how to compose music with GEMS. Lorenzen says "even though Jon was, and is, a techno composer and DJ, he had to learn from scratch the craft of sound for games and innovate new and wacky ways to punish the FM synthesizer chip on the Genesis to play the sounds it did."[1] Holland and the team spent a great deal of time listening to contemporary electronic artists like Kraftwerk, Orbital, and Prodigy to get a feel for the game's intended soundtrack.

Richard Karpp states that "during initial discussions of the story, we wanted a main theme for the game to be that passive entertainment, like television, was inferior to interactive entertainment."[1] These ideas eventually evolved into a television show-like plot roughly inspired by the 1987 film The Running Man, in which a deadly game show is highly-televised during a dystopian future (with specific inspiration taken from the movie's anti-television message.) Dana Christianson, upon hearing Weesner expand on this storyline, asked a personal friend, Patrick Brogan, to write up some possible new storylines. Brogan quickly authored about eight to ten different plots for Vectorman, one of which was chosen by Karpp for the final game.

As development progressed and the game began to take on an identity of its own, Vectorman's current appearance began to replace much of the game's initial television show concept. However, one of few story points from this period of development to remain in the final game is its anti-television message. As Karpp says it, "you destroy a lot of TVs to get powerups."[1]

A number of the studio's developers look back to Vectorman as one of their fondest memories of the 16-bit era. Mark Botta says "the experience of developing Vectorman was perhaps the best of my career. We pushed the Genesis to the limit. I felt like I knew every detail of how it worked. I never felt that way about any subsequent console."[1] Amber Long remembers that the teamwork and passion visible in the game's development was "fantastic", and that much of the development cycle's fast problem-solving and creative process was made easy by the close chemistry of Vectorman's developers.

| “ | Vectorman is probably the only truly original game I ever worked on. I’m eternally grateful for having had that opportunity. Working with Rich and Mark was wonderful and one of the most truly collaborative processes I’ve ever been through. I still have people telling me how much they like the game, so it’s an honor to have contributed to video game history in a notable way. | „ |

Development material

Development diary written by animator Marty Davis.

Earlier sketchbook produced by designer Mark Lorenzen.

Later sketchbook produced by designer Mark Lorenzen.

Tech demo created for the game's pitch.[1]

A 1995 email from Shinobu Toyoda to Jerry Markota concerning Sega of Japan's reception to seeing Vectorman.[1]

Concept artwork

"Bunker", used for development inspiration.[4]

A scrapped swamp stage which appeared in Vectorman 2.

A scrapped swamp stage which appeared in Vectorman 2.

Timeline

| CollapseTimeline (Mega Drive) |

|---|

08 09 10 11 1995-07-24: Prototype; 1995-07-24

1995-10-25: US release 1995-11-30: EU release, UK release |

References

- ↑ Jump up to: 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 1.12 1.13 1.14 1.15 1.16 1.17 https://thegameofnerds.com/2021/06/29/vectorman-genesis-climate-activist-turns-25/

- ↑ https://thegameofnerds.com/2021/06/29/vectorman-genesis-climate-activist-turns-25/ (Wayback Machine: 2024-05-10 04:55)

- ↑ http://illustrationbymartydavis.com/blog/2021/3/vectorman-25th-anniversary (Wayback Machine: 2024-05-10 04:55)

- ↑ Jump up to: 4.0 4.1 http://illustrationbymartydavis.com/blog/2021/3/vectorman-25th-anniversary

| CollapseVectorman | |

|---|---|

|

Main page | Maps | Downloadable content | Changelog | Hidden content | Development | Magazine articles | Video coverage | Reception | Promotional material | Region coding | Technical information | Bootlegs

| |