|

|

| Line 7: |

Line 7: |

| | | releases={{releasesDC | | | releases={{releasesDC |

| | | dc_date_eu=1999-10-14 | | | dc_date_eu=1999-10-14 |

| − | | dc_rrp_uk=19.99 {{fileref|CVG UK 215.pdf|page=59}} | + | | dc_rrp_uk=19.99{{fileref|CVG UK 215.pdf|page=59}} |

| | | dc_date_de=1999 | | | dc_date_de=1999 |

| | | dc_rrp_de=59,95{{fileref|SegaMagazin DE 71.pdf|page=7}} | | | dc_rrp_de=59,95{{fileref|SegaMagazin DE 71.pdf|page=7}} |

Revision as of 13:25, 9 September 2016

|

| Dreamcast Controller

|

| Made for: Sega Dreamcast

|

| Manufacturer: Sega

|

| Release |

Date |

RRP |

Code |

|

| JP

|

1998-11-27

|

¥2,5002,500

|

|

|

JP

(Millenium 2000)

|

1999-12-16[3]

|

¥2,5002,500[3]

|

|

|

| US

|

1999-09-09

|

|

|

|

| EU

|

1999-10-14

|

|

|

|

| DE

|

1999

|

DM 59,9559,95[2]

|

|

|

| AU

|

1999

|

$49.9549.95

|

|

|

|

The Dreamcast Controller (ドリームキャスト コントローラ) is the primary interface for interacting with the Sega Dreamcast video game console. It was bundled with every system and is supported by every Dreamcast game.

Hardware

With the Dreamcast, Sega went back to using the term "controller" for its main form of input, having previously preferred the term "control pad" with the Sega Mega Drive and Sega Saturn. As is to be expected, it increments on ideas seen with previous Sega hardware, being the logical progression from the Saturn's 3D Control Pad, originally debuting in mid-1996 as a response to the Nintendo 64. However, the 3D Control Pad was not as widely adopted as perhaps hoped, so the Dreamcast is the first (and only) Sega console to be equipped with analogue controls straight out of the box.

On the top left of the controller sits an "analogue thumb pad" (analogue stick), above a four-way directional pad (D-Pad), a START button in the centre of the controller and  ,

,  ,

,  and

and  face buttons on the right. On top of the controller there are two analogue triggers,

face buttons on the right. On top of the controller there are two analogue triggers,  and

and  in the top-left and top-right, respectively. Unlike the Sega Saturn (and Mega Drive) there are no

in the top-left and top-right, respectively. Unlike the Sega Saturn (and Mega Drive) there are no  and

and  buttons, and the controller has moved past the need for a switch to toggle between analogue and digital modes, seen on the 3D Control Pad.

buttons, and the controller has moved past the need for a switch to toggle between analogue and digital modes, seen on the 3D Control Pad.

The most striking difference with the Dreamcast controller is its two "expansion sockets" on the top. Typically the first socket (in front) houses a VMU (as there is a gap to see the screen) while the one in back houses other expansions such as the Jump Pack.

The Dreamcast controller stands as Sega's largest standard control pad for any of their systems, and was not redesigned during the console's run. Over the years it has run into some criticism, primarily for being uncomfortable for those with larger hands, but also for the high sensitivity of the thumb pad. Furthermore its lack of a second thumb pad was a noticable disadvantage when compared to the PlayStation 2 (and original PlayStation in its later years). It was also the last mainstream video game controller not to have vibration features as standard.

One curious design feature is controller's lead, which comes out of the bottom, only to be looped back up and clipped in place so as not to get in the way. While unconventional, Sega appears to have designed it this way to assist with storage - that is to say, the lead can be wrapped around the controller and clipped at the end.

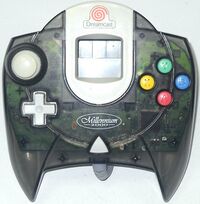

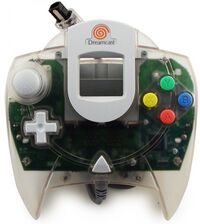

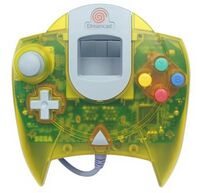

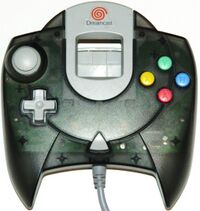

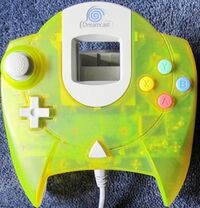

Many novelty Dreamcast controllers were produced in a wide variety of colours.

Internal workings

Although each button can be configured to perform a specific and distinctive action, all of the buttons, except for the two analog triggers and thumb pad, work on the same principle. In essence, each button is a switch that completes a circuit whenever it is pressed. A small metal disc beneath the button is pushed into contact with two strips of conductive material on the circuit board inside the controller. While the metal disc is in contact, it conducts electricity between the two strips.

The controller senses that the circuit is closed and sends that data to the Dreamcast. The CPU compares that data with the instructions in the game software for that button, and triggers the appropriate response. There is also a metal disc under each arm of the directional pad. If you're playing a game in which pushing down on the directional pad causes the character to crouch, a similar string of connections is made from the time of the push down on the pad to when the character crouches.

The analog thumb pad and triggers work in a completely different way from the buttons described above. The triggers each have a tiny magnet attached to the end of the trigger arm. When the trigger is depressed, the magnet is pushed toward a sensor mounted on the controller's circuit board. Through the process of induction, the magnet creates resistance to the current passing through the sensor. On the bottom of the magnet is a layer of foam padding. Pushing harder on the trigger compresses the padding, which brings the magnet closer to the sensor. The closer the magnet is to the sensor, the more resistance is induced. This variable resistance makes the triggers pressure-sensitive.

The thumb pad also uses a magnet, along with four small sensors. The sensors are arranged like a compass, with one at each of the cardinal points (north, south, east, west). The base of the joystick is shaped like a ball, with tiny spokes radiating out. The ball sits in a socket above the sensors. Spikes on the socket fit between the spokes on the ball. This allows for an extraordinary amount of movement without letting the thumb pad twist out of alignment with the sensors. As the thumb pad is moved, the magnet in the base moves closer to one or two of the sensors, and farther from the others. The system monitors the changes in induction caused by the magnet's movement to calculate the position of the thumb pad.

Gallery

Top of the controller, showing the two expansion sockets, analogue triggers and lead clip.

List of controllers

Japan

North America

Europe

Hardware Diagrams

References

![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() and

and ![]() face buttons on the right. On top of the controller there are two analogue triggers,

face buttons on the right. On top of the controller there are two analogue triggers, ![]() and

and ![]() in the top-left and top-right, respectively. Unlike the Sega Saturn (and Mega Drive) there are no

in the top-left and top-right, respectively. Unlike the Sega Saturn (and Mega Drive) there are no ![]() and

and ![]() buttons, and the controller has moved past the need for a switch to toggle between analogue and digital modes, seen on the 3D Control Pad.

buttons, and the controller has moved past the need for a switch to toggle between analogue and digital modes, seen on the 3D Control Pad.