Videogame Rating Council

From Sega Retro

The Videogame Rating Council (V.R.C.) was introduced by Sega of America in the summer of 1993 to rate the content of video games released for Sega systems (at this point, the Sega Mega Drive (Genesis), Sega Game Gear and Sega Mega CD (Sega CD)).

Sega voluntarily created this rating system in response to a growing public outcry over the supposed dangers of violent video games. It was phased out in late 1994 when the entire American video game industry agreed to follow the independent Entertainment Software Rating Board (ESRB).

Contents

Ratings

|

General Audiences: Appropriate for all audiences. No blood or graphic violence. No profanity, no mature sexual themes and no usage of drugs or alcohol. Examples of games with this rating are: Disney's Aladdin, Ecco the Dolphin, Earthworm Jim, Sonic the Hedgehog 3, Sparkster, and most sports and puzzle games. |

|

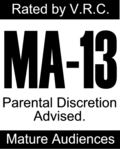

MA-13 — Mature Audiences: Parental Discretion Advised. The game was suitable for audiences thirteen years of age or older. Game could have some blood in it and more graphic violence than a "GA" game. Examples of games with this rating were Bram Stoker's Dracula, Flashback: The Quest for Identity, Super Street Fighter II, Lunar: The Silver Star, Wing Commander and Beavis and Butt-Head, and Zero the Kamikaze Squirrel |

|

MA-17 — Mature Audiences: Not appropriate for minors. The game was suitable for audiences seventeen years of age or older. Games could have lots of blood, graphic violence, mature sexual themes, profanity, drug or alcohol usage. Examples of games with this rating were: Leisure Suit Larry 6: Shape Up or Slip Out!, Lethal Enforcers, Mortal Kombat II, Rise of the Dragon and the Sega CD version of Mortal Kombat. |

|

NYR or, Not Yet Rated: This rating only appeared in advertising and indicated that the game had not yet been rated by the V.R.C. |

Initially VRC ratings used a simple black and white colour scheme as above, however ratings were often printed in colors matching the color scheme of the box (red for Genesis, purple for Game Gear and blue for Mega-CD). Sega of America also adapted this system for the French speaking customers of Canada, though it was vary rarely used.

History

Before 1993, Sega was known for a more liberal policy with regards to what type of content it would allow in a video game release on a Sega home console. Whereas Nintendo became famous for its strict censorship polices, Sega allowed blood and graphic violence in video games provided that such games had a generic parental advisory label on it.

The first company to take advantage of Sega's moral liberal polices was the company RazorSoft. In 1990 they released the 1988 computer game Technocop for the Genesis, in which bits of what was intended to be red blood would come out when you shot criminals and civilians (some of which were children). The game had limited commercial success, but RazorSoft would continue to use mature themes in video games which would occasionally stoke the more conservative press and public, including a port of Stormlord (with some nudity, later removed after pressure from Sega) and Death Duel.

In 1992 Namco released Splatterhouse 2 for the Genesis, a horror-themed side-scrolling action game, which like its arcade predecessor featured graphic violence (and was clearly inspired by the R-rated 1980 film Friday the 13th. Both RazorSoft and Namco put warnings on their game boxes, but there were no guidelines demanding that they should do so.

1992's Mortal Kombat and its subsequent home conversion is thought to have spurred Sega on to taking more affirmative action. The game was very popular precisely because it included digitised actors fighting in scenes of graphic violence. Fearing a public backlash, both major platform holders, Sega and Nintendo ordered for the game's depiction of blood to be toned down, of which publishers Acclaim obliged. Removing blood removed the very essence of the game however, so on the Sega versions, a blood code was kept hidden (although openly aluded to during the opening sequence and was even advertised on television).

To compensate, Sega created the VRC to inform parents of what it considered mature content, and Mortal Kombat was the first game to receive a VRC rating. There was a catch, however - publishers were concerned that higher ratings would eat into sales, so Sega only rated its middle MA-13 rating instead of the expected higher MA-17, as by default the game was considered less violent (i.e. you could not "accidentally" see the MA-17 content). Nintendo meanwhile censored the game, leading to the Genesis version outselling its Super NES counterpart.

Sega were nonetheless proud of its rating system and countined to use it for the next 18 months. It suggested that more than a third of Sega consumers were over 18[1] and that it was fair to cater for this market.

Sega did not roll out the VRC system in other markets (though Sega would later self-regulate games in Japan under a different (and more relaxed) system).

Criticism

Sega's rating system met its fair share of critics, and was openly attacked during the 1993 US congressional hearings on video games, which had been established following the release of games such as Mortal Kombat, Doom, Lethal Enforcers and Night Trap.

Sega's rating decisions were not transparent, and its terms for describing content were vague. There were questions about what Sega considered was "mature" (even its definition of mature spreading to 13-year-olds raised questions), and Sega initially seemed to avoid giving any games the MA-17 label, with Splatterhouse 3 also walking away with an MA-13.

Some saw it as an excuse for Sega to no longer censor content, leaving it to developers and publishers to decide (unlike Nintendo which policed everything released for its systems). While violence had been accepted in the past, Sega had still refused to license games with elements of nudity or profanity. Its views on topics such as religious iconography or homosexuality were less obvious, but with a rating system this could have given rise to any sort of content being released for a Sega system.

Sega itself were seemingly confused about its own policies, opting to drastically alter Bare Knuckle III when released as Streets of Rage 3 in the US (as MA-13). Despite the MA-17 label, both Rise of the Dragon and Snatcher had some of their mature images edited. The Mega-CD version of Mortal Kombat was released with an MA-17 label despite being much the same game as its Mega Drive predecessor, the only difference being the blood code was turned on by default.

Some publishers were concerned that the GA rating would put off older players, as they would not want to be associated with "kiddie games"[1]. There were suggestions that content would be added to push more games up to MA-13[1], thus being more in-line with the Sega audience.

As with other rating systems, Sega struggled to communicate how the VRC worked to the general public. As the system only applied to Sega games, and only Sega was enforcing it, it was up to the company to single-handedly both explain what a rating system was, and what the ratings actually meant.

Rivals Nintendo refused to even consider a rating system, believing that all Nintendo games should be suitable for all players[1]. Nintendo would later lobby against the very concept of violent video games, suggested by Sega as a plot to undermine their sales (Sega's typical audience being notably older than Nintendo's).

While some consumer groups commended Sega's attempts at rating content, it was suggested than an independant authority would serve the role better[1]. This is exactly what would happen with the formation of the ESRB, which all major North American video game publishers signed up to in 1994. It was argued (particularly in the early years) that the ESRB was no better, with vague "T" and "M" ratings that did not specify content, however the rules have been significantly tightened since then and it has remained a standard in North America ever since.