Difference between revisions of "History of the Sega Dreamcast"

From Sega Retro

| Line 6: | Line 6: | ||

When it emerged that Sony's hardware may have been more powerful than Sega's, three possible options crossed CEO [[Hayao Nakayama]]'s path. Either to press on with the Saturn project as is, upgrade it, or scrap it entirely in favour of another, superior console. As such, rumours of a "Saturn 2" console appeared as early as September 1994, possibly in the form of an add-on (similar to the [[Sega 32X]]) or as a replacement to the original Saturn within one or two years. | When it emerged that Sony's hardware may have been more powerful than Sega's, three possible options crossed CEO [[Hayao Nakayama]]'s path. Either to press on with the Saturn project as is, upgrade it, or scrap it entirely in favour of another, superior console. As such, rumours of a "Saturn 2" console appeared as early as September 1994, possibly in the form of an add-on (similar to the [[Sega 32X]]) or as a replacement to the original Saturn within one or two years. | ||

| − | Ultimately the decision was made to enhance the Saturn, and with the help of [[Hitachi]], extra processors were added to make the console arguably more powerful than the PlayStation. Unfortunately this came at a price, and the added complexities of this rushed design meant very few programmers could tap in to the Saturn's true potential. | + | Ultimately the decision was made to enhance the Saturn{{fileref|Edge UK 105.pdf|page=49}}, and with the help of [[Hitachi]], extra processors were added to make the console arguably more powerful than the PlayStation. Unfortunately this came at a price, and the added complexities of this rushed design meant very few programmers could tap in to the Saturn's true potential. |

===="Saturn 2"==== | ===="Saturn 2"==== | ||

| Line 63: | Line 63: | ||

While both the 3Dfx and PowerVR chips marked a significant improvement over the competition in terms of performance, the decision to abandon 3Dfx was met with disappointment and in some cases resentment among sections of the gaming world, particularly in the US, as the termination of the Black Belt contract led to sizable job losses at Sega of America. In particular, the choice to go for the Katana project puzzled Electronic Arts, a long time Sega partner who had invested in the 3Dfx company. This, along with poor Saturn sales, may have attributed to why the publisher refused to back the Dreamcast in its final iteration. | While both the 3Dfx and PowerVR chips marked a significant improvement over the competition in terms of performance, the decision to abandon 3Dfx was met with disappointment and in some cases resentment among sections of the gaming world, particularly in the US, as the termination of the Black Belt contract led to sizable job losses at Sega of America. In particular, the choice to go for the Katana project puzzled Electronic Arts, a long time Sega partner who had invested in the 3Dfx company. This, along with poor Saturn sales, may have attributed to why the publisher refused to back the Dreamcast in its final iteration. | ||

| − | 3Dfx were not pleased, believing that they were in the process of producing a chip that both met and in some cases exceeded Sega's expecations in terms of size, performance and cost. However, Sega's decision has also been attributed to 3Dfx leaking details and technical specifications of the then-secret | + | 3Dfx were not pleased, believing that they were in the process of producing a chip that both met and in some cases exceeded Sega's expecations in terms of size, performance and cost. However, Sega's decision has also been attributed to 3Dfx leaking details and technical specifications of the then-secret Black Belt project when declaring their Initial Public Offering in April 1997 (though 3Dfx had blanked most of its secrets out). Either way, Sega's investment in 3Dfx allowed them to lay claim to the technology behind the Black Belt project, to avoid it being used by competitors (such as Sony, who had expressed an interest){{fileref|EGM US 099.pdf|page=22}}. |

In response, 3Dfx filed a $155 million USD lawsuit in September against Sega and NEC, claiming that they had been misled into believing that their technology would be used when in fact a back-room deal had been done between the two Japanese companies in the months prior to the announcement{{intref|Press release: 1997-09-02: 3Dfx Interactive Files Lawsuit Against Sega Enterprises, Sega of America and NEC Corporation}}. They also claimed that Sega deprived 3Dfx of confidential materials in regards to 3Dfx's intellectual property. The lawsuit was settled in August 1998, with Sega paying USD $10.5 million to 3Dfx. | In response, 3Dfx filed a $155 million USD lawsuit in September against Sega and NEC, claiming that they had been misled into believing that their technology would be used when in fact a back-room deal had been done between the two Japanese companies in the months prior to the announcement{{intref|Press release: 1997-09-02: 3Dfx Interactive Files Lawsuit Against Sega Enterprises, Sega of America and NEC Corporation}}. They also claimed that Sega deprived 3Dfx of confidential materials in regards to 3Dfx's intellectual property. The lawsuit was settled in August 1998, with Sega paying USD $10.5 million to 3Dfx. | ||

| Line 73: | Line 73: | ||

Interestingly NEC Electronics' project manager for the PowerVR series, [[Charles Bellfield]] would join Sega of America's marketing team in July 1999{{intref|Press release: 1999-07-28: Sega Continues Building Executive Roster With Additions to Marketing Department}}. | Interestingly NEC Electronics' project manager for the PowerVR series, [[Charles Bellfield]] would join Sega of America's marketing team in July 1999{{intref|Press release: 1999-07-28: Sega Continues Building Executive Roster With Additions to Marketing Department}}. | ||

| − | It seemed as if Microsoft no longer had a role in the console's development, however 1998 was also the period where they announced another operating system, codenamed "Dragon" was available to Katana users - one based on its [[Windows CE]] technologies. Initially it was thought the | + | It seemed as if Microsoft no longer had a role in the console's development, however 1998 was also the period where they announced another operating system, codenamed "Dragon" was available to Katana users - one based on its [[Windows CE]] technologies. Initially it was thought the Katana could be bridging the gap between home PCs and video game consoles, however this was revealed not to be the case. Windows CE was intended to attract developers from Windows 95/98, presenting a less daunting development environment for those who had not worked on consoles before. |

Microsoft decided to cooperate with Sega in an attempt to promote its Windows CE operating system for video games, but Windows CE for the Dreamcast showed very limited capabilities when compared to the Dreamcast's native operating system. The libraries that Sega offered gave room for much more performance, but they were sometimes more difficult to utilize when porting over existing PC applications. Numerous Sega executives have gone on record stating that they felt the native OS was faster and more powerful, but the deal did give Microsoft the much needed knowledge for its [[Xbox]] project. | Microsoft decided to cooperate with Sega in an attempt to promote its Windows CE operating system for video games, but Windows CE for the Dreamcast showed very limited capabilities when compared to the Dreamcast's native operating system. The libraries that Sega offered gave room for much more performance, but they were sometimes more difficult to utilize when porting over existing PC applications. Numerous Sega executives have gone on record stating that they felt the native OS was faster and more powerful, but the deal did give Microsoft the much needed knowledge for its [[Xbox]] project. | ||

| Line 79: | Line 79: | ||

There were also troubles with Electronic Arts. Sega's financial position meant they were unable to offer the same generous offers which kept the company by their side in previous generations. | There were also troubles with Electronic Arts. Sega's financial position meant they were unable to offer the same generous offers which kept the company by their side in previous generations. | ||

| − | Then-CEO of EA, Larry Probst (a friend of Bernie Stolar) allegedly put forward a deal which only saw EA sports games being released on the | + | Then-CEO of EA, Larry Probst (a friend of Bernie Stolar) allegedly put forward a deal which only saw EA sports games being released on the Katana platform for five years, potentially leading to market dominance. Sega could not meet the terms of this agreement, and neither did they appear to want to - [[Visual Concepts]] was bought by Sega for USD $10 million and the widely held view was that their next NFL game (''[[NFL 2K]]'') would out-perform the likes of ''Madden 2000''. Sega attempted to get a better offer for them, but EA would not budge, leading to a Dreamcast without any support from the company at all. |

During the first half of 1998 several details were leaked concerning the Katana project and a similar [[Sega Model 3]] arcade replacement, the "[[NAOMI]] project", such as the concept of memory cards with built-in screens and a built-in modem{{fileref|Edge UK 058.pdf|page=11}}. Later, talk of proprietary disc formats, NAOMI-Dural memory card relationships and the name "Dream" appearing in the system's name{{fileref|Edge UK 059.pdf|page=9}}. | During the first half of 1998 several details were leaked concerning the Katana project and a similar [[Sega Model 3]] arcade replacement, the "[[NAOMI]] project", such as the concept of memory cards with built-in screens and a built-in modem{{fileref|Edge UK 058.pdf|page=11}}. Later, talk of proprietary disc formats, NAOMI-Dural memory card relationships and the name "Dream" appearing in the system's name{{fileref|Edge UK 059.pdf|page=9}}. | ||

| Line 89: | Line 89: | ||

===[[Sega New Challenge Conference]]=== | ===[[Sega New Challenge Conference]]=== | ||

On the 21st May, 1998 the Dreamcast console was shown to the world for the first time, at a Sega press event, the [[Sega New Challenge Conference]]. The intention was to release the system in Japan in November 1998. Supposedly the console was set to be revealed on the 10th, but this clashed with the announcement of Square Enix's ''Final Fantasy VIII''{{fileref|Edge UK 059.pdf|page=9}}. | On the 21st May, 1998 the Dreamcast console was shown to the world for the first time, at a Sega press event, the [[Sega New Challenge Conference]]. The intention was to release the system in Japan in November 1998. Supposedly the console was set to be revealed on the 10th, but this clashed with the announcement of Square Enix's ''Final Fantasy VIII''{{fileref|Edge UK 059.pdf|page=9}}. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The final name was one of 5,000 ideas brought forward by branding company Interbrand{{fileref|Edge UK 105.pdf|page=50}}. | ||

Sega's tactics were unusual for Japan - the Dreamcast would be supported along with the Saturn, primarily handling 3D titles. The Saturn would do 2D, however the move to announce the Dreamcast was seen by many Japanese developers as unnecessary solely because the Saturn was holding its ground quite nicely. Sega had expected a PlayStation 2 to be released in late 1999 (it was actually early 2000) and wanted to build up a year's worth of titles in advance to stall Sony's efforts. Similarly, delays in western regions were put in place to give the console a strong launch lineup. | Sega's tactics were unusual for Japan - the Dreamcast would be supported along with the Saturn, primarily handling 3D titles. The Saturn would do 2D, however the move to announce the Dreamcast was seen by many Japanese developers as unnecessary solely because the Saturn was holding its ground quite nicely. Sega had expected a PlayStation 2 to be released in late 1999 (it was actually early 2000) and wanted to build up a year's worth of titles in advance to stall Sony's efforts. Similarly, delays in western regions were put in place to give the console a strong launch lineup. | ||

| Line 215: | Line 217: | ||

The Dreamcast began to be teased in the summer of 1999, through a strange and potentially ineffective "it's thinking" marketing campaign. While the orange swirl and launch date were in sight, the console was not, leading ponteital customers to wonder ''what'' was thinking. It has been suggested that if you were not following events in the gaming industry, you might not even realise during this period that Sega were releasing a video games console (or indeed, if Sega were even involved). | The Dreamcast began to be teased in the summer of 1999, through a strange and potentially ineffective "it's thinking" marketing campaign. While the orange swirl and launch date were in sight, the console was not, leading ponteital customers to wonder ''what'' was thinking. It has been suggested that if you were not following events in the gaming industry, you might not even realise during this period that Sega were releasing a video games console (or indeed, if Sega were even involved). | ||

| + | |||

| + | In fact, in their New York test market, only 45% of the demographic the television adverts were aimed at knew that a "Dreamcast" was coming, but very few knew what a Dreamcast was{{fileref|Edge UK 105.pdf|page=50}}. Print adverts were equally confusing - the "weather map" for example showed a Dreamcast swirl off the East coast of America, meant to symbolise an "oncoming storm". Unfortunately for Sega, storms already look like this, so it was perceived that Sega had spent thousands of dollars on drawing some clouds{{fileref|Edge UK 105.pdf|page=51}}. | ||

Nevertheless Dreamcast pre-orders were said to be around the 200,000 mark (potentially rising closer to a 300,000 figure; some of which were back-dated six months in advance of launch{{ref|https://archive.org/stream/NextGen60Dec1999/NextGen_60_Dec_1999#page/n9/mode/2up}}) - roughly twice (or three times) the amount of pre-orders for the original PlayStation in 1995 and enough for Sega to claim it was the most anticipated video game console in history. Its year long delay also came with some advantages - games such as ''Blue Stinger'' and ''Sonic Adventure'' were able to be improved for their Western releases, while others such as the critically panned ''[[Godzilla Generations]]'' were not released in the US at all. | Nevertheless Dreamcast pre-orders were said to be around the 200,000 mark (potentially rising closer to a 300,000 figure; some of which were back-dated six months in advance of launch{{ref|https://archive.org/stream/NextGen60Dec1999/NextGen_60_Dec_1999#page/n9/mode/2up}}) - roughly twice (or three times) the amount of pre-orders for the original PlayStation in 1995 and enough for Sega to claim it was the most anticipated video game console in history. Its year long delay also came with some advantages - games such as ''Blue Stinger'' and ''Sonic Adventure'' were able to be improved for their Western releases, while others such as the critically panned ''[[Godzilla Generations]]'' were not released in the US at all. | ||

| Line 260: | Line 264: | ||

===Europe=== | ===Europe=== | ||

[[File:PlayStationBestBefore DC UK Advert.jpg|thumb|right|"PlayStation: Best Before 14/10/99"]] | [[File:PlayStationBestBefore DC UK Advert.jpg|thumb|right|"PlayStation: Best Before 14/10/99"]] | ||

| − | Much like North America, the Sega Saturn was out of the picture by 1998, considered to have been a "failure" and no longer a viable platform for video game development. Like the US, this gave competitors an almost two year advantage over Sega. | + | Much like North America, the Sega Saturn was out of the picture by 1998, considered to have been a "failure" and no longer a viable platform for video game development. Like the US, this gave competitors an almost two year advantage over Sega, squeezing its market share to around 3%{{fileref|Edge UK 105.pdf|page=50}}. |

The UK, being the largest games market in Europe, was again the centre of attention for much of Sega's European operations, with a £60 million marketing budget for Christmas 1999. The PlayStation had been ahead since 1995, but rather than being challenged significantly by the Nintendo 64, extended its lead with blockbusters such as ''Gran Turismo'', ''Final Fantasy VII'' and ''Metal Gear Solid'', owning a 75% share of the UK market by the Dreamcast's launch{{ref|http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/business/466765.stm}}. | The UK, being the largest games market in Europe, was again the centre of attention for much of Sega's European operations, with a £60 million marketing budget for Christmas 1999. The PlayStation had been ahead since 1995, but rather than being challenged significantly by the Nintendo 64, extended its lead with blockbusters such as ''Gran Turismo'', ''Final Fantasy VII'' and ''Metal Gear Solid'', owning a 75% share of the UK market by the Dreamcast's launch{{ref|http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/business/466765.stm}}. | ||

| Line 270: | Line 274: | ||

After long speculation about whether the European Dreamcast would have a built-in modem, the system was given the same 1999-09-09 release date as in the US... before it was subsequently pushed back to the 23rd of September, and then at the last minute, the 14th of October 1999. The delay was reportedly down to BT's handling of the [[Dreamarena]] service, having to negotiate with telecoms providers in mainland Europe, and such was the commitment to online Sega Europe refused to release the console until this service was done. | After long speculation about whether the European Dreamcast would have a built-in modem, the system was given the same 1999-09-09 release date as in the US... before it was subsequently pushed back to the 23rd of September, and then at the last minute, the 14th of October 1999. The delay was reportedly down to BT's handling of the [[Dreamarena]] service, having to negotiate with telecoms providers in mainland Europe, and such was the commitment to online Sega Europe refused to release the console until this service was done. | ||

| − | + | While not as cryptic as the advertising seen in the US, European adverts decided to emphasis the "lifestyle" of the Dreamcast machine, which meant very few games on display. An "up to six billion players" slogan had to be dropped after the UK's Advertising Standards Authority ruled that the system did not yet support online play{{fileref|Edge UK 105.pdf|page=51}}. This led to Sega ditching its choice of advertising agency (and by extension, any advertising campaigns over the launch period) until a couple of months down the line (starting with ''[[Sega Bass Fishing]]''){{fileref|Edge UK 105.pdf|page=51}}. | |

| + | |||

| + | This was not the only time Dreamcast advertising was forced off the airwaves - stereotyping continental rivals in a bid to advertise online play was pulled after the ITC ruled it could incite racial hatred{{fileref|Edge UK 105.pdf|page=51}}. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The Dreamcast was priced at £199.99 in the UK - the cheapest video game console release on record (though on import US and Japanese machines would have costed around £150 and £130, respectively). There were various festivities during the launch night, notably boxers [[wikipedia:Chris Eubank|Chris Eubank]] and [[wikipedia:Nigel Benn|Nigel Benn]] fighting for the first time since 1993... through ''[[Ready 2 Rumble Boxing]]''{{fileref|Arcade UK 13.pdf|page=18}}. 3,000 uses registered on Dreamarena in the first 24 hours{{fileref|Arcade UK 13.pdf|page=18}}. | ||

In response to the Dreamcast's launch, Sony lowered the price of its PlayStation to £79.99. | In response to the Dreamcast's launch, Sony lowered the price of its PlayStation to £79.99. | ||

| Line 289: | Line 297: | ||

===Australia/New Zealand=== | ===Australia/New Zealand=== | ||

| − | The Australian region the launch was labeled a disaster by many fans of Sega. [[Ozisoft]], the official Sega distributor in Australia, only managed to output nine launch titles despite the late release date (November 30, 1999), none of which were first party products. Apparently Sega-developed software had been held in customs and could not reach store shelves by the release date (which included ''Dream On'' demo discs, which had to be picked up by customers at a later date){{fileref|Hyper AU 076.pdf|page=6}}. | + | The Australian region the launch was labeled a disaster by many fans of Sega. [[Ozisoft]], the official Sega distributor in Australia, only managed to output nine launch titles despite the late release date (November 30, 1999), none of which were first party products. Apparently Sega-developed software had been held in customs (for being "insufficiently labeled"{{fileref|Edge UK 105.pdf|page=51}}) and could not reach store shelves by the release date (which included ''Dream On'' demo discs, which had to be picked up by customers at a later date){{fileref|Hyper AU 076.pdf|page=6}}. |

With no [[VMU]]s or other peripherals on the market, it seemed that after what seemed like infinite delays, Australian fans deserved better. Moreover no Australian advertising campaign came into force until the system had been released - the general public could have easily been taken unaware. | With no [[VMU]]s or other peripherals on the market, it seemed that after what seemed like infinite delays, Australian fans deserved better. Moreover no Australian advertising campaign came into force until the system had been released - the general public could have easily been taken unaware. | ||

| Line 346: | Line 354: | ||

Nevertheless Sega persued the concept of online gaming through the likes of ''[[Phantasy Star Online]]'' and its sequels, and with the introduction of Xbox Live and the subsequent "seventh generation" of consoles (starting with the [[Xbox 360]] in 2005, online gaming and interaction similar to how Sega had envisoned it is now the norm. | Nevertheless Sega persued the concept of online gaming through the likes of ''[[Phantasy Star Online]]'' and its sequels, and with the introduction of Xbox Live and the subsequent "seventh generation" of consoles (starting with the [[Xbox 360]] in 2005, online gaming and interaction similar to how Sega had envisoned it is now the norm. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Reportedly at its height, a third of European Dreamcast owners had subscribed to [[Dreamarena]], but only 15% of US Dreamcast customers had done the same{{fileref|Edge UK 105.pdf|page=53}}. | ||

===Lessons=== | ===Lessons=== | ||

| Line 363: | Line 373: | ||

Without a strong footing in the Western world, it can be argued that Sega did not have a firm grasp of what its American (and European) customers wanted. In 1993 for example, Sega of America secured the rights to the blockbuster film, ''[[Jurassic Park (Mega Drive)|Jurassic Park]]'' and made big profits from its tie-in game. Equally the release of ''[[Eternal Champions]]'' played into the hands of the ''[[Mortal Kombat]]'' phenomenon - with decisions being made in Japan (and thus more likely to follow Japanese trends) Sega of America were unable to repeat this success in 1999. | Without a strong footing in the Western world, it can be argued that Sega did not have a firm grasp of what its American (and European) customers wanted. In 1993 for example, Sega of America secured the rights to the blockbuster film, ''[[Jurassic Park (Mega Drive)|Jurassic Park]]'' and made big profits from its tie-in game. Equally the release of ''[[Eternal Champions]]'' played into the hands of the ''[[Mortal Kombat]]'' phenomenon - with decisions being made in Japan (and thus more likely to follow Japanese trends) Sega of America were unable to repeat this success in 1999. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ====Distribution==== | ||

| + | Compared to the PlayStation, the Dreamcast distribution service was not well received by Western retailers. If a store was seen to be selling large numbers of PlayStation consoles, Sony would offer discounts on bulk ordering and increased credit limits. Sega offered no such incentives, and was also slow to recredit retailers for faulty items. Furthermore it offered no price protection for price drops, and was considered to be biased towards large multiples, as opposed to smaller outlets{{fileref|Edge UK 105.pdf|page=50}}. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Fundamentally this meant that retail was more likely to stock PlayStations than Dreamcasts (and indeed Saturns from the previous generation) on the grounds of retail deals alone. | ||

====Perceptions and bias==== | ====Perceptions and bias==== | ||

| Line 378: | Line 393: | ||

From a software point of view, the Dreamcast was frequently praised. Hardware shortages plagued the early years of the PlayStation 2, and the Dreamcast is thought to have achieved more in eighteen months than the Nintendo 64 had managed in five years. Furthermore the Dreamcast could boast many features the PlayStation 2 could not - while it lacked the native DVD playback capability (an extremely significant factor in 2000/2001), it would take many years until a competitor could match Sega's online presence. | From a software point of view, the Dreamcast was frequently praised. Hardware shortages plagued the early years of the PlayStation 2, and the Dreamcast is thought to have achieved more in eighteen months than the Nintendo 64 had managed in five years. Furthermore the Dreamcast could boast many features the PlayStation 2 could not - while it lacked the native DVD playback capability (an extremely significant factor in 2000/2001), it would take many years until a competitor could match Sega's online presence. | ||

| − | Dreamcast games almost always ran in 640x480 (versus the usual 512x448 for PS2 titles), often with PAL60 support for European and Australian markets, and in most cases picture quailty that could go up to VGA standard. Even [[Nintendo]]'s [[Wii]], released as late as 2006 lacks a comparable video option. Sony were late to pick up some ideas, such as allowing more than two players to use the system locally | + | Dreamcast games almost always ran in 640x480 (versus the usual 512x448 for PS2 titles), often with PAL60 support for European and Australian markets, and in most cases picture quailty that could go up to VGA standard. Even [[Nintendo]]'s [[Wii]], released as late as 2006 lacks a comparable video option. The Dreamcast is also said to have better support for 50Hz television setups than the PlayStation 2{{fileref|Edge UK 105.pdf|page=53}}. |

| + | |||

| + | Sony were late to pick up some ideas, such as allowing more than two players to use the system locally without add-ons (the PS2, incidentally, is thought by some to have purposely limited its options for the benefit of peripheral manufacturers{{fileref|Edge UK 105.pdf|page=53}}). It was also a while until the PS2 could match the Dreamcast's low price and physical size. | ||

Early PlayStation 2 games suffered from anti-aliasing issues, causing polygons to look less smooth than what was being seen on the Dreamcast (and hinted at with the upcoming Xbox){{ref|https://archive.org/stream/NextGen68Aug2000/NextGen_68_Aug_2000#page/n15/mode/2up}}. | Early PlayStation 2 games suffered from anti-aliasing issues, causing polygons to look less smooth than what was being seen on the Dreamcast (and hinted at with the upcoming Xbox){{ref|https://archive.org/stream/NextGen68Aug2000/NextGen_68_Aug_2000#page/n15/mode/2up}}. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The PlayStation 2 port of ''[[Dead or Alive 2]]'' is sometimes cited as an example of the Dreamcast-PS2 dilemma. During the game (and console's) development, the PlayStation 2 version was expected to be dramatically superior to the Dreamcast port, however in reality, it is the Dreamcast version that is often seen as superior (despite the system costing less). It is said that only after the PlayStation 2's launch did people realise how good the Dreamcast actually was{{fileref|Edge UK 105.pdf|page=50}}. | ||

===Legacy=== | ===Legacy=== | ||

Revision as of 07:51, 13 March 2016

Contents

Development

Pre-announcement

Sega Saturn

Such was the state at Sega at the time, a successor to the Sega Saturn was being considered by the firm even before the console had been released. After a series of talks with Nintendo for a CD-based add-on for the Super Nintendo console broke down, Sony unveiled their stand-alone PlayStation system in November 1993, rattling Sega's management considerably. Sega had not seen Sony as a threat until this point, worried instead of what Nintendo may have had in-store with their presumed successor to the Super Nintendo.

When it emerged that Sony's hardware may have been more powerful than Sega's, three possible options crossed CEO Hayao Nakayama's path. Either to press on with the Saturn project as is, upgrade it, or scrap it entirely in favour of another, superior console. As such, rumours of a "Saturn 2" console appeared as early as September 1994, possibly in the form of an add-on (similar to the Sega 32X) or as a replacement to the original Saturn within one or two years.

Ultimately the decision was made to enhance the Saturn[1], and with the help of Hitachi, extra processors were added to make the console arguably more powerful than the PlayStation. Unfortunately this came at a price, and the added complexities of this rushed design meant very few programmers could tap in to the Saturn's true potential.

"Saturn 2"

Though the Saturn sold fairly strongly in Japan during 1995, talks of the Saturn 2 were still on the table, as developers across the world were becoming ever more displeased with Sega's recent offering. It emerged that the Saturn 2 project was no longer in the exclusive hands of Sega - Lockheed Martin, who had assisted the company with the graphics powering the Sega Model 1 and Sega Model 2 arcade boards, were now in charge of the Saturn 2 project, with a focus primarily on graphical power[2].

At the time, Lockheed Martin were working on their "Real3D" series of chipsets for Windows-based PCs, and the Saturn 2 was rumoured to use the R3D/100 chipset as a base for its graphics[3]. PC graphics were not yet "standardised" at this time - DirectX had yet to be invented and though Lockheed Martin were working with the now widely used OpenGL technology, there were a vast array of competing video cards on the market.

Doubts began to be cast towards the end of the year, due to Sega's increased frustrations with Lockheed Martin, who were simultaneously working on the Sega Model 3 arcade platform. The Model 3, once set for release in late 1995, wasn't due to be seen until mid-1996, causing Sega to temporarily lose its competitive edge in the arcades.

At this time, Sega parntered with the rising graphics company, NVIDIA, who based their first video card, the NV1 off the Sega Saturn hardware (even allowing for Saturn controllers to be plugged in via a second board). NVIDIA had a hard time persuading Sega that the technology was the future, however - Sega were already sceptical due to the PlayStation's early success, and even though Sega converted several Saturn games to benefit from the NV1, sales of the video card were poor. NVIDIA reportedly started to work on a successor, the NV2 but the project was shelved. Had it been finalised, the technology behind the NV2 would likely have likely replaced the R3D/100 graphics chipset for Sega's next console.

M2 and DVD

In 1991, founder of Electronic Arts Trip Hawkins left the company to start a new venture - the 3DO Company, with the aim of breaking into the lucrative video game console market with a high-end system, the aptly named 3DO Interactive Multiplayer. 3DO Company would design the specifications, and in what was considered a novel move at the time, license out the technology to electronics manufacturers who would build the systems. The aim was to create a uniform standard similar to what is generally seen in the music and film industries, and in a sense follow traditions set up by the IBM PC and MSX in Japan.

However, when it launched in late October 1993, the 3DO was too expensive and unable to effectively compete with the giants of Sega, Nintendo and eventually Sony. By late 1994 the firm had announced an add-on to the 3DO, later to become its own separate console, with the codename "M2". For much of the mid-1990s the M2 was the subject of much discussion, thought to be a powerful device more than capable of threatening the competition.

In early 1996 the M2 was currently in the phase of being an arcade platform, being sold to Japanese electronics giant Matsushita (now trading as Panasonic). Around this time, Sega, presumably displeased with the delays of Lockheed Martin, entered discussions with the firm, potentially suggesting a plan to abandon their Model 3 platform entirely.

In February, Sega ordered some M2 development kits in a deal which would see them provide the system exclusively with games[4], but over the weeks and months, talks broke down. Inevitably a mixture of egos and reports of poor performance led to Sega abandoning the M2 project shortly afterwards[5], and the Sega Model 3 board was finalised and put to market. The Model 3 would be Sega's last deal with Lockheed Martin - the two companies would part ways shortly afterwards, so Lockheed Martin's "Saturn 2" project was effectively put to rest.

Sega initially denied they were talking to Matsushita about the M2, but instead were exploring the possibilities behind the upcoming DVD disc standard (Matsushita being a founding member of the DVD Forum (along with Sony)). Sega were to work with the firm to utilise DVD technology in home entertainment[6], though little appears to have come of it.

Incidentally Sega would later partner with Yamaha to create the GD-ROM standard for use in its latest console. This kept initial costs down as Sega did not have to pay royalties to the DVD Forum, although Sega would insist that DVD remained an option for the future. Matsushita would later abruptly cancel the M2 project shortly before release in mid-1997, and eventually provide the disc technology behind the Nintendo GameCube, Wii and Wii U.

"Dural" and "Black Belt"

Nintendo's new console, the Nintendo 64, was released in September 1996, and with it, the supposed world of 64-bit gaming, and while the Saturn continued to sell well in Japan, the N64 started to dramatically eat into the Saturn's market share. The PC market was also continuing to evolve, being dominated by two graphics standards - the PowerVR series by VideoLogic, and the Voodoo cards by 3Dfx. Sega chose to approach both companies in 1996, effectively starting two "Saturn 2" projects which would work in parallel until mid-1997. Now the mission was to one-up Nintendo.

Development on VideoLogic's project would occur in Japan, and was quickly given the code name "Dural" (named after a character from Sega AM2's Virtua Fighter series). In the US, 3Dfx would work on a project known as "Black Belt"[7]. Shoichiro Irimajiri came to office in 1997, and having assessed the situation decided to hire Tatsuo Yamamoto, a former IBM engineer, to work on the Black Belt project. Hideki Sato, however, got wind of this idea, and joined the Dural project with his team. Though both were seprate operations, the two were following the same trends and inevitably made similar decisions, causing a great deal of confusion across the gaming press at the time.

It was Dural which made the first public move, when Hitachi, a company who had already played a role in the Sega 32X and Sega Saturn's development, announced it would be making the CPU for the Japanese machine. This turned out to be the Hitachi SH-4 processor architecture (codenamed "White Belt"), which would be used in conjunction with NEC/Videologic's upcoming PowerVR Series II (codenamed "Guppy") graphics chips in the production of their main board.

However, Western commentators typically spoke of the Black Belt project, as by 1996/1997, 3Dfx were the leaders in the PC video card market. Yamamoto and his group opted to use 3Dfx's Voodoo 2 and Voodoo Banshee graphics technology, and after initially trying RISC processors from IBM and Motorola, settled on the SH-4 as the CPU of choice as well. Sega would buy a 16% stake in 3Dfx in mid-1997[8], presumably as a sign as commitment to the company's efforts.

From a software perspective, Sega were actively seeking partnerships in 1997, though there was still much uncertainty in regards to the details. Talks began with Microsoft for undisclosed reasons, and SegaSoft found themselves on-board with Black Belt development.

At one stage the Black Belt, was shown to a limited number of developers and was apparently very well received. Details of this Western "64-bit" machine were not hard to come by[9], but perhaps the most important feature of the Black Belt design was its operating system, designed specifically to make the machine easy to develop for (likely moreso than the Dural project at that stage[10]).

At the time Sega's policy seemed to suggest that raw processing power wasn't as important as an easy to develop for operating system (one of the many pitfalls with the Saturn). The OS was designed to aid in quick conversions of games to and from the PC. Furthermore the Black Belt project was backed by newly recruited Sega of America COO, Bernie Stolar, who had already began to attempt to discontinue the struggling Sega Saturn in the region, even going as far to claim the system was "not our future" at E3 1997.

Sega were thought to have been showing off development hardware to prospective developers and publishers around late 1997, with a converted demo version of Scud Race[11]. Notably the Sega Saturn had built a reputation of only offering arcade conversions - with the Dural, Sega wanted a more diverse selection of games, and so despite experimenting with Scud Race, a full conversion of the title was unlikely. The upcoming Daytona USA 2: Battle on the Edge was considered a more likely candidate, but in the end this did not materialise either.

Incidentally demos concerning Scud Race have since been found on Dreamcast Dev.Boxes.

Preliminary development on the Dural platform was starting to take shape in late 1997, with Sega informing developers to use Intel Pentium II-powered computers clocked at 200MHz with PowerVR graphics cards as a foundation[12].

One curious fact confirmed by Hideki Sato is that at some point, Sega's new console was to abandon traditional electronic heat sinks and opt for a water-cooling system in order to keep its components cool[13].

"Katana"

In early 1998 the Dural project publically became known as "Katana"[14], at a time when Sega Saturn was on its last legs. Electronic Arts dropped its Saturn support and Western versions of X-Men vs. Street Fighter seemed increasingly unlikely - a new console was sorely needed, and Sega Europe were setting a date for 1999[15].

Initially, Sega decided to use Yamamoto's design and suggested to 3Dfx that they would be using their hardware in the upcoming console, but a change of heart caused them to use Sato's PowerVR-based design instead[16]. There are conflicting reports claiming whether the "Katana" was more powerful than the "Black Belt" or vice versa - Sonic Team and Dreamcast developer Yuji Naka was caught in 1998 stating that ports of Sonic Adventure to the PC was impossible, because 3DFX's Voodoo cards were significantly less powerful than what was in the Katana console[17].

Alternatively, some suggested it was Microsoft that pushed for the NEC-backed project, as at the time, a close relationship between the two companies meant millions of NEC computers were shipping with Microsoft products as standard[18].

While both the 3Dfx and PowerVR chips marked a significant improvement over the competition in terms of performance, the decision to abandon 3Dfx was met with disappointment and in some cases resentment among sections of the gaming world, particularly in the US, as the termination of the Black Belt contract led to sizable job losses at Sega of America. In particular, the choice to go for the Katana project puzzled Electronic Arts, a long time Sega partner who had invested in the 3Dfx company. This, along with poor Saturn sales, may have attributed to why the publisher refused to back the Dreamcast in its final iteration.

3Dfx were not pleased, believing that they were in the process of producing a chip that both met and in some cases exceeded Sega's expecations in terms of size, performance and cost. However, Sega's decision has also been attributed to 3Dfx leaking details and technical specifications of the then-secret Black Belt project when declaring their Initial Public Offering in April 1997 (though 3Dfx had blanked most of its secrets out). Either way, Sega's investment in 3Dfx allowed them to lay claim to the technology behind the Black Belt project, to avoid it being used by competitors (such as Sony, who had expressed an interest)[19].

In response, 3Dfx filed a $155 million USD lawsuit in September against Sega and NEC, claiming that they had been misled into believing that their technology would be used when in fact a back-room deal had been done between the two Japanese companies in the months prior to the announcement[20]. They also claimed that Sega deprived 3Dfx of confidential materials in regards to 3Dfx's intellectual property. The lawsuit was settled in August 1998, with Sega paying USD $10.5 million to 3Dfx.

With Katana marked as the way forward, VideoLogic revealed details on their upcoming PowerVR Series II graphics chip in early 1998[21], with commentators suggesting it could achieve parity with the Sega Model 3 board for roughly $99 USD (versus the Model 3's $6000 price tag at the time).

More debatable was whether it could match 3Dfx's Voodoo 2 chipset in terms of performance, however VideoLogic's deal with NEC meant PowerVR II chips could be manufactured for half the price - key for the Katana to hit its $199.99 price target. 3Dfx, meanwhile, were a much smaller organisation with no direct access to manufacturing facilities - the proven track record of NEC (and likely its Japanese origins) likely played a part in Sega's decision to side with their neighbours.

Interestingly NEC Electronics' project manager for the PowerVR series, Charles Bellfield would join Sega of America's marketing team in July 1999[22].

It seemed as if Microsoft no longer had a role in the console's development, however 1998 was also the period where they announced another operating system, codenamed "Dragon" was available to Katana users - one based on its Windows CE technologies. Initially it was thought the Katana could be bridging the gap between home PCs and video game consoles, however this was revealed not to be the case. Windows CE was intended to attract developers from Windows 95/98, presenting a less daunting development environment for those who had not worked on consoles before.

Microsoft decided to cooperate with Sega in an attempt to promote its Windows CE operating system for video games, but Windows CE for the Dreamcast showed very limited capabilities when compared to the Dreamcast's native operating system. The libraries that Sega offered gave room for much more performance, but they were sometimes more difficult to utilize when porting over existing PC applications. Numerous Sega executives have gone on record stating that they felt the native OS was faster and more powerful, but the deal did give Microsoft the much needed knowledge for its Xbox project.

There were also troubles with Electronic Arts. Sega's financial position meant they were unable to offer the same generous offers which kept the company by their side in previous generations.

Then-CEO of EA, Larry Probst (a friend of Bernie Stolar) allegedly put forward a deal which only saw EA sports games being released on the Katana platform for five years, potentially leading to market dominance. Sega could not meet the terms of this agreement, and neither did they appear to want to - Visual Concepts was bought by Sega for USD $10 million and the widely held view was that their next NFL game (NFL 2K) would out-perform the likes of Madden 2000. Sega attempted to get a better offer for them, but EA would not budge, leading to a Dreamcast without any support from the company at all.

During the first half of 1998 several details were leaked concerning the Katana project and a similar Sega Model 3 arcade replacement, the "NAOMI project", such as the concept of memory cards with built-in screens and a built-in modem[23]. Later, talk of proprietary disc formats, NAOMI-Dural memory card relationships and the name "Dream" appearing in the system's name[24].

Meanwhile the US launch was being slowly pushed back, starting in Christmas 1998, then moving back to March 1999, and then April 1999[25] before finally settling on September. Stolar nevertheless had big ambitions - a $100 million marketing campaign for 1999 and plans to both secure and exceed 50% of the North American video games market[26].

By the spring of 1998 development kits had been sent to select developers, with the hardware being highly praised[27]. Many publishers signed up to the console during this period, including supposedly Electronic Arts, who had plans at this stage to bring many games to the system[28].

Sega New Challenge Conference

On the 21st May, 1998 the Dreamcast console was shown to the world for the first time, at a Sega press event, the Sega New Challenge Conference. The intention was to release the system in Japan in November 1998. Supposedly the console was set to be revealed on the 10th, but this clashed with the announcement of Square Enix's Final Fantasy VIII[24].

The final name was one of 5,000 ideas brought forward by branding company Interbrand[29].

Sega's tactics were unusual for Japan - the Dreamcast would be supported along with the Saturn, primarily handling 3D titles. The Saturn would do 2D, however the move to announce the Dreamcast was seen by many Japanese developers as unnecessary solely because the Saturn was holding its ground quite nicely. Sega had expected a PlayStation 2 to be released in late 1999 (it was actually early 2000) and wanted to build up a year's worth of titles in advance to stall Sony's efforts. Similarly, delays in western regions were put in place to give the console a strong launch lineup.

The internals of the Dreamcast were reportedly finalised, though a final colour had not yet been chosen, with controllers (and VMUs) available in yellow, red, blue and grey colour schemes[30]. Interestingly Sega had originally planned to distance its company name from the brand - unlike production Dreamcasts (and North American advertising), no "SEGA" lettering was to be found on the console, likely in an attempt to hide the history of the Saturn, Sega 32X and Sega Mega-CD.

E3 1998

On the 27th of May, the day prior to the start of E3 1998, Sega of America president Bernie Stolar re-announced that the Dreamcast existed and was coming to North America in the Autumn of 1999, with a planned total of 20-30 launch games[31]. No games were announced, but a couple of tech demos were shown - likely the same as a week prior, but as the gaming press were forbidden to take photos of even describe what was on show, it cannot be confirmed at this stage.

Bernie's Dreamcast had a red controller and two red VMUs. At E3 itself no Dreamcast produce was on display, just a handful of Sega Saturn titles and PC releases.

Windows World Expo Tokyo 98

Between the 1st and 4th of July, 1998, Microsoft held their own Japanese expo for upcoming Windows products. Among those, the Windows CE-compatible Dreamcast, still not in its final form.

Unlike the Sega New Challenge Conference where prototype Dreamcasts were kept in glass cases or behind closed doors, here the console could be picked up and even powered on, confirming that "something" was in the shell, even though it wasn't connected to a television.

The Dreamcast on display still lacked its final shell, as evidenced by the lack of "Powered by Windows CE" text next to the controller ports. Instead, a crudely attached sticker was placed on the front of the console, with a promise that the final version would have this message printed on the shell itself[32].

Sega New Challenge Conference II and Tokyo Game Show '98 Autumn

Held a few days before Tokyo Game Show '98 Autumn, Sega detailed its pricing strategy and launch titles, and tied up loose ends about what the final console package would contain[33]. A few weeks prior, Dreamcast launch date was put back five days[34].

At TGS Dreamcast games were made available to the public for the first time, and Sega detailed its internet strategy.

The year long gap between the Japanese and Western releases of the Dreamcast saw a few important events. It is said that Bernie Stolar went against his Japanese superiors by pricing the Dreamcast with a launch price of USD $199 (which he unveiled in a speech in early 1999, to standing ovation). Reportedly, Sega Japan wanted to price the DC at USD $249 in order to be very profitable right from the start. Stolar was fired before the Dreamcast's launch.

Issues were also raised with the PAL variant of the Dreamcast console. Its logo was feared to infringe trademarks with German publisher, Tivola. This is why PAL logos are blue.

Prototypes

The following three prototype Dreamcasts were displayed at TGS Autumn '98:

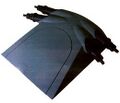

"Bread Bin" Design

Though most prototype designs were confined to the drawing board, Sega produced a few physical prototypes, the most radical is this "wedge" or "bread bin" design, unlike any video game console released before or since. This is apparently cited as being the "first" prototype, or at least, earlier than the two which follow.

It appears to sport four controller "ports" and has a lid, where presumably games would be inserted. It is grey and lacks names or logos.

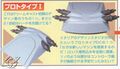

"Vortex"

The second design is far more similar to the final product, though seems to be taking design lessons from the western Sega Saturn. The four controller ports are now housed at the front, similar to the Nintendo 64, and there are two buttons, one to presumably open the lid, and another to turn the unit on. It is clear from this stage that the reset button of the Saturn would not be included in the Dreamcast.

On the top is the text "Vortex" with its own logo.

"White Box"

The third iteration is far more similar to the final product. It is now white, has a power LED and a window to see the disc spinning (which would be omitted from the final design).

Others

Controller

The Dreamcast controller was derived from the Sega Saturn's 3D Control Pad. Every prototype Dreamcast controller acknowledges the need for an analogue stick.

Curiously some designs are not symmetrical, in that the left hand side is physically bigger than the right, presumably to allow to be more easily operated with one hand. This was a design trait briefly explored with the Saturn's 3D Control Pad before it was finalised.

Air NiGHTS Controller

Yuji Naka was involved in the Dreamcast project during its conception, though inevitably got caught up in Sonic Adventure's development towards the end. It is rumoured, however, that the NiGHTS into Dreams team influenced a design of the Dreamcast controller - one built like a remote and with motion sensors, almost a decade before the Wii entered the market. It was to be used in conjunction with the Air NiGHTS project.

Visual Memory Unit

Early VMU designs looked similar, if not more colorful, than the final product.

Release

Japan

Japan's relationship with the Dreamcast is hard to judge, as its release is often considered to be premature. The Sega Saturn had been a successful venture for the company, and Japanese publishers failed to see the need for a new console, so when the system debuted on the 27th of November 1998 in Japan, the demand was perhaps less significant than in the West.

Sega's initial strategy was to run the two consoles in parallel, 2D games being housed on the Saturn and 3D on the Dreamcast, though this became less and less tennable as time went on.

Four titles were available at launch: July, Pen Pen TriIcelon, Virtua Fighter 3tb, and Godzilla Generations. Within three days 140,830 consoles had been sold (of the 150,000 available units, bearing in mind this figure includes promotional and development units). Virtua Fighter 3tb was the biggest seller (debuting second in the software charts of that week), followed by Godzilla (16th), Pen Pen (21st) and July (25th)[35].

A Japanese launch generally sees the console effectively sold out at launch, as the vast majority of systems and games are pre-ordered weeks and months in advance. In the Dreamcast's case this led to some criticism, as the four launch titles were not well received by much of the gaming press. Furthermore Sega put a lot of spin in its press releases - while the console was indeed sold out and shortages were common throughout the Christmas 1998 period (as "demand outstripped supply"), this was because of a shortage of PowerVR 2 graphics chips. As NEC was unable to produce enough components (about 30% of what was anticipated), Sega's initial projection of 300,000 units was effectively halved[36].

The original plan was to release one game a week for four weeks following the launch, Blue Stinger on the 3rd of December, Geist Force on the 10th, Sonic Adventure on the 17th and the combined batch of Evolution, Incoming, Monaco Grand Prix: Racing Simulation 2 and Seventh Cross Evolution on the 23rd. However half of these titles were delayed at the last minute, many being pushed back to March 1999 and Geist Force being cancelled outright[37]. Planned launch title Sega Rally 2 was also affected, being knocked back to January, while Sonic Adventure saw a two week delay.

However, roughly one in three consumers logged onto the internet using the bundled Dream Passport service, which greatly exceeded expectations.

Initial predictions by Sega were that the PlayStation 2 would debut in late 1999 (it was actually early 2000 in Japan). The aim was to attract as many developers as possible within a year to attempt to secure the Dreamcast as the number one consoles of its generation. A 1 million units sold target for March 31st was set by management, though in the end the shipping figure is thought to have been around 900,000 across Asia, with potentially about 800,000 units actually sold (no official figures exist for this period and are third-party estimates from across Q2 1999).

Keeping with the now long-running trend, Dreamcast releases were spread thin across the first half of 1999, to the point where the Nintendo 64 is thought to have out-performed Sega's new console. In the beginning of June, Sega held the Sega New Challenge Conference '99, and the console's price was lowered to ¥19,900[38], with the four launch games dropping to ¥1,990 (and changes coming into effect on the 24th[39]). Sales rose by 10,000% and 65,000 units were sold in four days[40]. A few months later, Sega got caught in a raid by Japanese officials for allegedly pressuring retailers to stick to that price[41].

The spike subsided and sales continued to be sluggish - the 1.1 million sales for the fiscal year of 1999 was missed, with Sega only managing to sell 950,000 units in Japan[42]. Peter Moore, however announced at this time that there were roughly 330,000 Japanese members of the region's Dreamcast network[43].

By the Summer of 2000, 2.1 million Dreamcasts had been sold in Japan[42].

With the Mega Drive, Sega had identified the US and Europe as the largest video game markets. With the Saturn and Dreamcast, they felt (perhaps wrongly) that Japan was the key territory. As such, like the Saturn, the Dreamcast was subjected to many games exclusive to Japan, along with numerous exclusive peripherals and special Dreamcast models.

North America

There was never a plan to launch the Dreamcast in the US simultaneously with Japan. Instead, Sega forced Western consumers to wait ten months, to both analyse the situation in their home market, and so as not to repeat the mistakes with the Sega Saturn. The US launch was therefore set on the 9th of September 1999 (9/9/99) - perhaps the most famous console launch date of all time.

Shoichiro Irimajiri claimed the delay was to allow the Dreamcast to launch with wider variety of games (it ended up being 4 (JP) vs. 18 (US)) - the first time a Sega console would launch with "enough" titles. There were big plans, but with lacklustre Japanese sales for much of the first half of 1999, Sega of America initially kept quiet about their upcoming system.

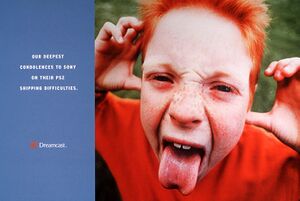

The Dreamcast began to be teased in the summer of 1999, through a strange and potentially ineffective "it's thinking" marketing campaign. While the orange swirl and launch date were in sight, the console was not, leading ponteital customers to wonder what was thinking. It has been suggested that if you were not following events in the gaming industry, you might not even realise during this period that Sega were releasing a video games console (or indeed, if Sega were even involved).

In fact, in their New York test market, only 45% of the demographic the television adverts were aimed at knew that a "Dreamcast" was coming, but very few knew what a Dreamcast was[29]. Print adverts were equally confusing - the "weather map" for example showed a Dreamcast swirl off the East coast of America, meant to symbolise an "oncoming storm". Unfortunately for Sega, storms already look like this, so it was perceived that Sega had spent thousands of dollars on drawing some clouds[44].

Nevertheless Dreamcast pre-orders were said to be around the 200,000 mark (potentially rising closer to a 300,000 figure; some of which were back-dated six months in advance of launch[45]) - roughly twice (or three times) the amount of pre-orders for the original PlayStation in 1995 and enough for Sega to claim it was the most anticipated video game console in history. Its year long delay also came with some advantages - games such as Blue Stinger and Sonic Adventure were able to be improved for their Western releases, while others such as the critically panned Godzilla Generations were not released in the US at all.

Strictly speaking the first person to receive an official American Dreamcast (and "first party Sega games for life") was the winner of a Sonic the Hedgehog lookalike contest Sega of America held roughly a month before launch. For everyone else, 15,000 retail stores across the nation were given stock for launch and 400 took part in special Dreamcast launch parties[46]. Sega hired some celebrities and sponsored the MTV music awards, all as part of an initial $100 million advertising campaign.

The Dreamcast (alongside its eighteen launch games and accessories) took in $97,904,618.09 USD on the first day of launch in North America[46], and sold over 500,000 machines in the first two weeks, nearly 400,000 of which were in the first four days. Sega were quick to point out that $97 million is more than Star Wars: The Phantom Menace brought in its opening weekend (roughly $65 million), although it wasn't yet making a profit.

The launch was not without problems - there were a string of defective discs concerning Sonic Adventure, Blue Stinger and Ready 2 Rumble Boxing[46], originating from a specific processing plant which prefixed its disc codes with "92"[47]. Otherwise the period was viewed as a success, and does not appear to have been significantly affected by the PlayStation release of Final Fantasy VIII, launched on the same day. Sega also struggled to keep up with demand, with consoles, VMUs and controllers all in short supply[45].

Over a million machines were sold in North America in just over two and a half months (according to Peter Moore, the milestone was reached on Tudesday 23rd November[48]). This meant the Dreamcast was the fastest selling video games machine in North America of all time.

However, initial sales failed to make significant inroads into the PlayStation's market share. Instead, it was the Nintendo 64 that suffered - with Electronics Boutique claiming being N64s were being traded in for Dreamcasts at three times the rate of Sony's console[45]. Sonic Adventure and SoulCalibur topped the Dreamcast sales charts, though the out-right winner over the first few weeks is thought to have been NFL 2K[45].

Sega of America actually changed its name (temporarily) to "Sega of America Dreamacst, Inc." in support of the machine[43].

Sales of the Dreamcast caused Sega to adjust their sales projections for the US. Bernie Stolar had originally put a target for 1.5 million units for March 31st, 2000 - this target was moved forward to December 31st, 1999 and a new 2 million target was put in for March 31st[48].

1.5 million Dreamcasts were sold by January 2000[49] - slightly later than Peter Moore's projection, but far earlier than Stolar's. However, it was not a Dreamcast victory - 1.9 million Nintendo 64s were sold during Q4 1999, and 3.3 million PlayStations[50].

Sega's commitment to putting the Dreamcast online cannot be underestimated. Shortly before launch a deal was struck with networking giant AT&T, who would provide the online infrastructure to Sega in return for being the Dreamcast internet service provider of choice[51]. Users could subscribe to one of three tiers of online usage (the top, $21.95/month "unlimited" plan coming with a free Dreamcast Keyboard) which would cover everything internet-related, including the future prospect of online multiplayer.

Roughly 2.5 million Dreamcasts were thought to have been sold in the US by March 31st, 2000[42].

By the Spring 2000 Sega were offering their own ISP, SegaNet, for low-latency online play geared specifically for Dreamcast consoles. Sega even offered free Dreamcasts to those who signed up with the service, in an effort to greatly increase the Dreamcast install base (the caveat being users had to sign up for minimum of two years at $21.95 per month)[52].

Mid-2000 saw the hardware to software ratio for the Dreamcast at a respectible 8:1[53].

Problems arose when the PlayStation 2 started to make headlines, first with its successful Japanese launch (also towards the back-end of 1999) and then its subsequent US release. In Sega's absense the PlayStation brand had become a driving force in the video game industry, so much so that many were prepared to hold back from buying a Dreamcast, anticipating that Sony's console would serve their needs better. On the day Sony announced the US launch date and price for the PS2, Sega enhanced their SegaNet deal, now giving users a $50 rebate to spend on games[54].

But while the PS2 ran roughshod over the Dreamcast in Japan, the US launch was more controversial - in Sega camps the PlayStation 2 was seen as a more expensive unit with a weaker initial library of games, and yet it went on to break records.

Going into Christmas 2000, Sega initially countered the PlayStation 2 launch, by dropping the the price of the Dreamcast to $149.99[55], in turn leading to a 156% increase in sales. A target was put in place to reach 4.5 million - 5 million units sold by March 2001[56].

Sony's launch was dogged by supply and distribution problems, a higher price tag (which was excaserbarted by the low stock levels - auction sites were offering PS2s for as much as $800[57]), so Sega held out for the so called "PlayStation 2" effect - dissatisfied consumers opting for the cheaper Dreamcast as an alternative. This never quite happened as intended - US retail concerning electronic goods was unusally low in the week after Thanksgiving, as people waited out the crowds[58].

In fact, the Dreamcast only sold 463,750 units in December 2000, versus 515,000 PlayStations and 640,000 Nintendo 64s. According to NPD figures the Dreamcast was responsible for 22% of the North American console sales in 1999 (PlayStation 48%, Nintendo 64 30%), but this had fallen to 15% in 2000 (PlayStation (and PlayStation 2) 47%, Nintendo 64 37%).

Nevertheless Sega of America ran a short campaign mocking Sony as a two page spread in GameWeek, on postcards, and reportedly, on the side of a truck which drove around Electronic Arts' headquarters in Redwood City, California[59].

At the announcement of the Dreamcast's discontunation at the end of January 2001, 3 million Dreamcasts had been sold overall[58]. On February 4th, 2001, the price of the Dreamcast was cut again to $99.95 ($149 CND)[60].

Production of North American Dreamcasts ceased in November 2001, several months after Sega announced plans to leave the console business. Despite this, the Dreamcast is seen to have been more successful than the Sega Saturn (and Sega Master System) in this region.

Europe

Much like North America, the Sega Saturn was out of the picture by 1998, considered to have been a "failure" and no longer a viable platform for video game development. Like the US, this gave competitors an almost two year advantage over Sega, squeezing its market share to around 3%[29].

The UK, being the largest games market in Europe, was again the centre of attention for much of Sega's European operations, with a £60 million marketing budget for Christmas 1999. The PlayStation had been ahead since 1995, but rather than being challenged significantly by the Nintendo 64, extended its lead with blockbusters such as Gran Turismo, Final Fantasy VII and Metal Gear Solid, owning a 75% share of the UK market by the Dreamcast's launch[61].

Nintendo was still in the race, but was beginning a long-running trend of having very little software to choose from - only about 120 N64 titles were available on the UK market by mid-1999, though the system had been on sale since March 1997.

Roughly 50 Dreancast games had been greenlit for a European release by July 1999[62].

After long speculation about whether the European Dreamcast would have a built-in modem, the system was given the same 1999-09-09 release date as in the US... before it was subsequently pushed back to the 23rd of September, and then at the last minute, the 14th of October 1999. The delay was reportedly down to BT's handling of the Dreamarena service, having to negotiate with telecoms providers in mainland Europe, and such was the commitment to online Sega Europe refused to release the console until this service was done.

While not as cryptic as the advertising seen in the US, European adverts decided to emphasis the "lifestyle" of the Dreamcast machine, which meant very few games on display. An "up to six billion players" slogan had to be dropped after the UK's Advertising Standards Authority ruled that the system did not yet support online play[44]. This led to Sega ditching its choice of advertising agency (and by extension, any advertising campaigns over the launch period) until a couple of months down the line (starting with Sega Bass Fishing)[44].

This was not the only time Dreamcast advertising was forced off the airwaves - stereotyping continental rivals in a bid to advertise online play was pulled after the ITC ruled it could incite racial hatred[44].

The Dreamcast was priced at £199.99 in the UK - the cheapest video game console release on record (though on import US and Japanese machines would have costed around £150 and £130, respectively). There were various festivities during the launch night, notably boxers Chris Eubank and Nigel Benn fighting for the first time since 1993... through Ready 2 Rumble Boxing[63]. 3,000 uses registered on Dreamarena in the first 24 hours[63].

In response to the Dreamcast's launch, Sony lowered the price of its PlayStation to £79.99.

Initial European sales figures looked healthy, with over 100,000 machines sold in Europe on launch day alone (42,000 of those being UK pre-orders[63]) and over 185,000 in the first weekend. By Christmas weekly hardware sales in the UK were doubling that of the Nintendo 64, though were significantly less than the cheaper PlayStation[64]. Dreamcast games were also retailing for about £40 - £20 less than some of the N64 big hitters such as Donkey Kong 64.

Not all regions performed up to expectations. Only 40,000 Dreamcast were sold at launch in Germany (despite some retailers launching the system two days early), far short of the predicted sales figures of 80,000-100,000 units[65].

Sega Europe set a target of one million units sold by May 2000. About 500,000 had been sold by Christmas, and the Dreamcast was responsible for about 5.4% of video game console sales (including handhelds) in 1999 (Game Boy 9.1%, Nintendo 64 15.4%, PlayStation 69.4%, others 0.7%)[66].

Despite being noticably smaller than Japan and the US, the Dreamcast library was widely praised in the UK, likely as a result of decisions not to publish games that fared poorly in other regions. However, desipte this Sega had a hard time selling software - very rarely did a Dreamcast game make it into the weekly top 20 sales charts, and while a typical first-party Sega game could appeal to the gaming press, its new ideas and untested intellectual properties were sidelined by the general public, which typically opted for brands it knew on the PlayStation.

On 8 September 2000, Sega Europe reduced the price in the UK to £149.99[67] in response to the arrival of the PlayStation 2, but despite delays, hardware shortages, a higher price point and limited array of launch software, Sony's machine, complete with the backing of many third-party publishers (and 300+ games announced for the system before launch), ultimately eclipsed the Dreamcast within six months of sale.

After news of the impending cancellation of the Dreamcast in 2001, the system's price was lowered to £99.99 on the 14th of February[68], leading to a surge in Dreamcast sales and a reported 5,000 consoles sold in the UK per week[69]. With the launch of Skies of Arcadia in April, software prices were capped at £29.99 too.

The Dreamcast lasted longer in Europe than in North America, and was officially discontinued completely in the spring of 2002.

Australia/New Zealand

The Australian region the launch was labeled a disaster by many fans of Sega. Ozisoft, the official Sega distributor in Australia, only managed to output nine launch titles despite the late release date (November 30, 1999), none of which were first party products. Apparently Sega-developed software had been held in customs (for being "insufficiently labeled"[44]) and could not reach store shelves by the release date (which included Dream On demo discs, which had to be picked up by customers at a later date)[70].

With no VMUs or other peripherals on the market, it seemed that after what seemed like infinite delays, Australian fans deserved better. Moreover no Australian advertising campaign came into force until the system had been released - the general public could have easily been taken unaware.

The Dreamcast took a while to get online in Australia, arriving in the back end of Q1 2000. A deal between Telstra and Ozisoft saw comma.com.au become the default Dreamcast homepage, powered by a similar Dreamkey service to Europe.

Generally the console isn't thought to have done well in Australia, with retailers such as The Games Wizards pulling the system within six months of sale.

Brazil

Tectoy, who had been responsible for distributing Sega consoles in Brazil since the Sega Master System, brought the Dreamcast to Brazil on October 4, 1999. The majority of games were repackaged titles imported from the US, and the console was not particularly successful.

South Korea

Breaking from the tradition of partnering with Samsung, in South Korea the Sega Dreamcast was reportedly distributed by Hyundai, the company who, curiously, had carried Nintendo products in the country during the 90s. Unlike the rest of the world, the Dreamcast arrived late in South Korea and was priced as a budget console competing against the PlayStation 2 and Xbox. 25,000 units were shipped before Hyundai cancelled the project for unknown reasons. South Korean Dreamcasts were supposedly bundled with modem cables to take advantage of the system's online services.

Some Korean developers were reportedly developing games for the Dreamcast before the plug was pulled. Arcturus and White Day, both eventually released on the PC, were once set to be released on the console.

Decline

The true reasons for the Dreamcast's dimise are the subject of debate, however on January 30, 2001, Sega announced an end date for the hardware - March 31st, timed as such so that the company's losses on the console could be tied in to the 2000/2001 financial year[71].

In the mid-1990s, riding off the success of the Sega Mega Drive and their mascot, Sonic the Hedgehog, Sega had embarked on overly ambitious plans - to be the largest and most dominant video game force on the market, and a world leader in entertainment - a Japanese equivalent to Disney. But struggles with the Saturn and other pressures came back to bite the firm - by the late 1990s Sega were making heavy losses, causing the empire to be put on hold.

May 2000 saw Isao Okawa replace Shoichiro Irimajiri as president of Sega (Irimajiri taking a lesser role, before leaving the company at the end of January 2001[72]). Hayao Nakayama, who had also been in the chair during Sega's rise to fame was also out the door, and Okawa (who had invested heavily in Sega - having loaned the firm $500 million USD in 1999) lacked the faith of these two men. Even as early as 1999, Okawa was claiming the Dreamcast would be Sega's last console[73], and his vision of a third-party online-centric software developer was soon shared by many of the big Sega names in America, including Peter Moore, Charles Bellfield and former Sega grandee David Rosen (who had reportedly held this position for seven years - after the decline of the Mega Drive[74]).

In the last few months of 2000 Sega began issuing statements about their desire to work on non-Sega platforms, at this stage being hand-held PDAs, mobiles, Bandai's WonderSwan and the Game Boy Advance[59]. There were also plans to license a "DC chip" - Dreamcast technology which could then be used in set-top boxes or DVD players, though none of these projects ever materialised[59]. Acclaim Entertainment also let slip details of PlayStation 2 ports of Crazy Taxi, 18 Wheeler: American Pro Trucker and Zombie Revenge[59] two of which they would end up publishing for the platform.

Sega made a last ditch attempt at recruiting developers by offering new a development solution - the $5,000 USD "Independent Development Toolkit" (IDT), designed to circumvent the reported $15,000-$20,000 dedicated development kits Sega had been distributing since the Katana days (said to be an equivalent price to far more powerful Xbox dev kits at the time). This would have consisted solely as a cable and some software, designed to work on any standard PC and off-the-shelf Dreamcast console[75]. While the IDT would not have granted access to the entirity of the Dreamcast system, it would have allowed for less intensive, often online focused games that could be built cheaply, Sega Swirl being cited as an example. It is not known how many of these kits were sold (if indeed any were).

Despite initial reluctance, Sega of Japan finally pulled the plug on the Dreamcast project roughly three weeks after Christmas[76].

It is widely considered that Sega were unable to compete with Sony's PlayStation 2 and Microsoft's new Xbox console when it came to marketing[76]. The Xbox advertising campaign eclipsed anything Sega could put together, and was cited as a reason not to continue. However, it is known many in Sega were symphathetic to Microsoft's cause - Bernie Stolar for example (now in charge of Mattel), advocated a deal which saw Microsoft buying Sega and working on a joint platform. Others were wary that the big names of Electronic Arts and Square Enix, third-party leaders in the US and Japan, respectively, were still not on board the Dreamcast project, and others such as Eidos and Infogrames had already severed ties with the system.

Note also that the Dreamcast was never put in a position where it had to compete against the GameCube or Xbox, both consoles launching in September and November 2001, respectively. Indeed, Sega contributed games to both console launches.

Sega's money issues would become a serious problem in the years that followed. A failed merger with Bandai and reported talks with Namco came to nothing (reports of a Nintendo-Sega takeover were also suggested, but denied by both companies), and having resisted a buy-out from Sammy, the two companies merged in 2004, creating Sega Sammy Holdings which would drastically streamline the organisation (there were also short talks with Sony and Microsoft who were interested in buying-out Sega too[76]). Nearly one-third of the Tokyo workforce was laid off in 2001, and the company didn't make a profit until 2003, after five years of consecutive losses.

It is difficult to determine whether the Dreamcast struggled significantly in the marketplace. Sega of America claimed to have difficulty attracting consumers outside of the "core" demographic[71] but more Dreamcasts were sold in the US in two years than the Saturn had in three. More than likely, the markups on hardware and software were not sufficient to counteract other financial pressures in the company, some of which stemmed from the Western Saturn's struggles, but also the declining arcade market, and multi-million dollar projects such as Shenmue.

Decisions to drop the Dreamcast and leave the hardware market were the more likely the result of an internal arguement, where it was decided that building games for a range of systems would increase potential profits. David Rosen for example suggested Sega could become one of the largest video game publishers in as little as two years[74].

On April 14th, 2001, Sega attended GameJam, fresh off the back of Yuji Naka winning numerous awards from CESA for the then-Dreamcast exclusive game Phantasy Star Online. As a tribute to the console, and to promote the remaining Dreamcast games set for release across 2001 (36 mentioned at the show), Naka was joined by Yu Suzuki and Noriyoshi Oba to an audience of potentially thousands as the Dreamcast was effectively signed off[77].