Difference between revisions of "Yokohama Joypolis/History"

From Sega Retro

m (→Demise) |

m (→Demise: Oh!... that's one of the racing drivers of H-factory Racing Team (Hiromi factory)... cool!!! :) ... see https://segaretro.org/Sponsorships/Motorsports) |

||

| (One intermediate revision by one other user not shown) | |||

| Line 24: | Line 24: | ||

Initial reviews of Yokohama Joypolis appear to have been mixed to positive, with some reviewers claiming some of the touted technological feats of the attractions did not meet their expectations, though several praised VR-1.{{ref|https://archive.org/details/sim_japan-times_august-08-14-1994_34_32/page/n9}}{{ref|https://web.archive.org/web/20210227065410/https://www.vrfocus.com/2020/07/the-virtual-arena-blast-from-the-past-the-vr-1/}} After the launch, Sega took advantage of the venue's large size and capacity for organised events to hold numerous examples, including notable ''[[Virtua Fighter]]''{{fileref|VirtuaFighter2EternalBattle VHS JP Box.jpg}} and ''[[Sega Rally Championship]]''{{fileref|Yokohama Sega Rally Time Attack Festival.jpg}} tournaments. These officially-held events were communicated through magazines handed out inside of the park, including [[SegaJack]] and [[Sega Magazine]], and would become a key aspect of subsequent Joypolis centres. A Skate GSJ skateboarding meet was also held at the park in the following months.{{ref|https://www.flickr.com/photos/gijon/albums/72057594101098549}} | Initial reviews of Yokohama Joypolis appear to have been mixed to positive, with some reviewers claiming some of the touted technological feats of the attractions did not meet their expectations, though several praised VR-1.{{ref|https://archive.org/details/sim_japan-times_august-08-14-1994_34_32/page/n9}}{{ref|https://web.archive.org/web/20210227065410/https://www.vrfocus.com/2020/07/the-virtual-arena-blast-from-the-past-the-vr-1/}} After the launch, Sega took advantage of the venue's large size and capacity for organised events to hold numerous examples, including notable ''[[Virtua Fighter]]''{{fileref|VirtuaFighter2EternalBattle VHS JP Box.jpg}} and ''[[Sega Rally Championship]]''{{fileref|Yokohama Sega Rally Time Attack Festival.jpg}} tournaments. These officially-held events were communicated through magazines handed out inside of the park, including [[SegaJack]] and [[Sega Magazine]], and would become a key aspect of subsequent Joypolis centres. A Skate GSJ skateboarding meet was also held at the park in the following months.{{ref|https://www.flickr.com/photos/gijon/albums/72057594101098549}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Operation== | ||

| + | On October 8th, 1994{{magref|sv|22|6}}, Yokohama Joypolis hosted the Japanese invitational tournament for the ''[[Sonic & Knuckles]]'' tournament [[Rock the Rock]]. Known as the World Championship Japan Tournament and attended by [[Yuji Naka]] himself{{fileref|RocktheRock YokohamaJoypolis YujiNaka.png}}, it was won by Hitoshi Kobayashi, who was promptly dressed in prison attire and flown to [[wikipedia:San Francisco, California|San Francisco, California]] for the next step of the tournament.{{fileref|MTV'SRocktheRockSonic&Knuckles1994 US Video.mp4}} | ||

==Demise== | ==Demise== | ||

| Line 29: | Line 32: | ||

Projected to make ¥3.6 billion and attract 1.2 million visitors in its first year of operation,{{intref|Press release: 1994-08-15:Shisetsu-nai Inshoku Tenpo Shirīzu 'Joiporisu' 120 Man Hito o Shūkyaku e}} Yokohama Joypolis exceeded this, surpassing expectations by generating roughly ¥4 billion{{ref|https://archive.org/details/contemporarybusi00boon/page/184}} and drawing in 1.75 million visitors.{{fileref|Segaworld Trocadero '96 Promo Video.mp4}} However, the park's flagship status was soon superseded by [[Tokyo Joypolis]] in 1996, and the venue appears to have subsequently struggled to create similar numbers. One factor attributed to this was the fact that the park, situated away from the central districts of Yokohama, was a fifteen-minute walk from the nearest subway station, something later rectified in 2004.{{ref|https://web.archive.org/web/19961224105332/http://www.sega.co.jp/sega/atp/yokohama/access.html}} | Projected to make ¥3.6 billion and attract 1.2 million visitors in its first year of operation,{{intref|Press release: 1994-08-15:Shisetsu-nai Inshoku Tenpo Shirīzu 'Joiporisu' 120 Man Hito o Shūkyaku e}} Yokohama Joypolis exceeded this, surpassing expectations by generating roughly ¥4 billion{{ref|https://archive.org/details/contemporarybusi00boon/page/184}} and drawing in 1.75 million visitors.{{fileref|Segaworld Trocadero '96 Promo Video.mp4}} However, the park's flagship status was soon superseded by [[Tokyo Joypolis]] in 1996, and the venue appears to have subsequently struggled to create similar numbers. One factor attributed to this was the fact that the park, situated away from the central districts of Yokohama, was a fifteen-minute walk from the nearest subway station, something later rectified in 2004.{{ref|https://web.archive.org/web/19961224105332/http://www.sega.co.jp/sega/atp/yokohama/access.html}} | ||

| − | After a period of downtime, the park reopened under the new name of Joypolis H. Factory Yokohama on 25 July 1999,{{ref|https://web.archive.org/web/20000410212153/http://www.sega.co.jp/sega/atp/news/news994/jpnews990725.html}} with its ground floor level undergoing a partial refurbishment in the process. Its operations were now assisted by media personality and businessman [[wikipedia:Hiromi (comedian)| Hiromi | + | After a period of downtime, the park reopened under the new name of Joypolis H. Factory Yokohama on 25 July 1999,{{ref|https://web.archive.org/web/20000410212153/http://www.sega.co.jp/sega/atp/news/news994/jpnews990725.html}} with its ground floor level undergoing a partial refurbishment in the process. Its operations were now assisted by media personality and businessman [[wikipedia:Hiromi (comedian)| Hiromi Kozono]], who at the time was developing several sports-themed leisure centres in Japan.{{magref|dmjp|1999-25|7}} A small number of new leisure attractions, such as go-kart tracks,{{ref|https://web.archive.org/web/20010210034529/http://www.sega.co.jp/sega/atp/news/news2000/jpnews0308_2.html}} were added to support the main Sega-developed examples in place since 1994, which had since received software and theming updates. |

Yokohama Joypolis closed permanently at the end of February 2001,{{ref|https://web.archive.org/web/20010211153412/http://www.sega.co.jp/sega/atp/yokohama/home.html}} changing admission fees to ¥15 and ¥10 to scrap payments for its attractions and arcade machines in its final weeks.{{ref|https://web.archive.org/web/20010629222429/http://www.sega.co.jp/sega/atp/news/news2001/jpnews0208.html}} The closure occurred in the midst of a restructuring at Sega, which also partially led to several other Joypolis venues as well as the overseas [[SegaWorld London]] and [[Sega World Sydney]] going defunct, a scrapping of the plans for 100 theme parks across the world, and the eventual discontinuation of the Amusement Theme Park concept, with managerial problems and cashflow issues cited.{{ref|https://www.vrfocus.com/2020/07/the-virtual-arena-blast-from-the-past-the-vr-1/}} Whilst some of its auxiliary facilities continued trading,{{ref|https://web.archive.org/web/20010629222429/http://www.sega.co.jp/sega/atp/yokohama/home.html}} the space the main building formerly occupied subsequently became warehouse storage again, and its former grounds have more recently been redeveloped to house an apartment complex.{{ref|https://www.google.com/maps/place/1-ch%C5%8Dme-14-18+Shinyamashita,+Naka+Ward,+Yokohama,+Kanagawa+231-0801,+Japan/@35.4409022,139.6562886,3a,75y,50.99h,90t}} | Yokohama Joypolis closed permanently at the end of February 2001,{{ref|https://web.archive.org/web/20010211153412/http://www.sega.co.jp/sega/atp/yokohama/home.html}} changing admission fees to ¥15 and ¥10 to scrap payments for its attractions and arcade machines in its final weeks.{{ref|https://web.archive.org/web/20010629222429/http://www.sega.co.jp/sega/atp/news/news2001/jpnews0208.html}} The closure occurred in the midst of a restructuring at Sega, which also partially led to several other Joypolis venues as well as the overseas [[SegaWorld London]] and [[Sega World Sydney]] going defunct, a scrapping of the plans for 100 theme parks across the world, and the eventual discontinuation of the Amusement Theme Park concept, with managerial problems and cashflow issues cited.{{ref|https://www.vrfocus.com/2020/07/the-virtual-arena-blast-from-the-past-the-vr-1/}} Whilst some of its auxiliary facilities continued trading,{{ref|https://web.archive.org/web/20010629222429/http://www.sega.co.jp/sega/atp/yokohama/home.html}} the space the main building formerly occupied subsequently became warehouse storage again, and its former grounds have more recently been redeveloped to house an apartment complex.{{ref|https://www.google.com/maps/place/1-ch%C5%8Dme-14-18+Shinyamashita,+Naka+Ward,+Yokohama,+Kanagawa+231-0801,+Japan/@35.4409022,139.6562886,3a,75y,50.99h,90t}} | ||

Latest revision as of 21:47, 3 December 2022

- Back to: Yokohama Joypolis.

Background

As far back as 1965, Sega had been opening and maintaining numerous "game corner" amusement facilities in Japan.[1] Yokohama's Golden Center Game Corner, opened in 1968, was among their earliest and largest.[2] Operations of these were initially small-scale, often involving rented locations, however they had seen boosts in the 1970s by the popularisation of video and medal games.[1] By the time of the mid 1980s, several well-established companies in the Japanese amusement industry including Sega were creating directly managed and branded chain stores, re-evaluating long-term ambitions, and creating larger machines in the midst of the rise of the Taikan games and "3K" cleanup campaign.[1] Spearheaded by Hayao Nakayama, Sega of Japan's operations divisions began working towards opening increasingly bigger venues that would broaden the appeal of game centers, increase customer bases, and strengthen their position in industry.[3]

Initial work on this trajectory was undertaken with the En-Joint concept in the early 1990s and the creation of the prolific Sega World suburban game centers.[3] When opening these, Sega executives quickly realised that due to their lack of similar produce, operations managers were frequently relying on large equipment sourced from other manufacturers to characterize the appeal of the facility.[4] Though a small amount of amusement pieces by other companies were allowed in Sega facilities, its own were strictly prioritised, thus now necessitating the need for a research and development division that produced such work.[4]

Off the back of the previous Sega Super Circuit and the in-progress R360, Sega AM5 was specifically formed to fulfil this purpose and commence development on a number of high-end interactive attractions for family entertainment.[5][6] However, inspired by the success of Disney's theme park business and in a technological arms race with Sega, competition soon came from Namco, with the launch of their indoor Plabo Sennichimae Tenpo in November 1991[7] and outdoor Wonder Eggs theme park in February 1992.[8] Both contained the highly-successful Galaxian 3 ride developed by the company.[9]

In response to this and as part of wider aspirations to grow on a level comparable to Disney,[10] Sega announced its intent to build a theme park business during October 1992, assembling the Amusement Theme Park concept and Amusement Theme Park Division[11] for the opening of a tentative first facility in Osaka.[12] The parks were to play into Sega's focus on "High-Tech Interactive Entertainment", utilising the large and mid-size attractions development efforts of the AM5 division. After a number of early works released in small quantities, its popular Virtua Formula and AS-1 simulators launched the following year in the now-numerous larger Sega game centers, with new openings like the urban Roppongi GiGO[13][14] and Sega World Hakkeijima Carnival House in Yokohama's Hakkeijima Sea Paradise aquarium theme park becoming more complex.[15][16]

Development

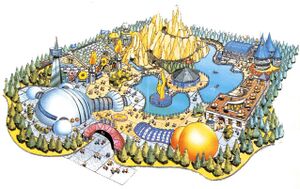

Concurrent with the indoor Osaka pilot facility, a larger theme park project was also being conceptualised by amusement facility planner Yoshiyasu Takada.[17] Provisional artwork and registered patents dated in the 1992-1993 period depict the concept of an outdoor Disneyland-like theme park,[12][18] containing enclosure buildings for many of its attractions to effectively follow the same steps as Namco's aforementioned indoor Plabo venue and outdoor Wonder Eggs park.[9] This concept and the original iterations of rides were discarded for unclear reasons, with Sega instead choosing to secure a plot of vacant land in Yokohama, Yamashita Park, where it could build an indoor complex; however, some ideas such as ghost trains and minecart rollercoasters would carry through into the finished park's attractions, planned by the likes of Hiroshi Uemura and Tokinori Kaneyasu.[5][19]

Though the principal planning and development of the park and its attractions were largely carried out by AM5, other Sega amusement R&D teams pitched in and collaborated on some aspects. During its initial inception, AM2 and AM3 had worked with AM5 to feature their software/3DCG works in the Virtua Formula, AS-1 and VR-1 simulators it designed, respectively. AM4 developed debuting attraction Mad Bazooka, with AM2's Takenobu Mitsuyoshi composing its music;[20] fellow department musician David Leytze also arranged "Independence", an original piece made to be played over the park's exterior sound system on opening day.[21] Additional background music for the facility and rides were composed by the likes of Koichi Namiki,[22] Hiroshi Kawaguchi,[23] Keisuke Tsukahara,[24] and Kazuhiko Nagai.[25] Mie Kumagai, a company newcomer at the time thanks to a successful job interview with Tetsuya Mizuguchi, produced a 3DCG film for the entrance, which would notably become her first completed work for Sega.[26]

Publicly, Sega gave little indication of the park's existence, keeping its progress tightly under wraps and non-disclosure agreements. [4] AM5 developer Hironao Takeda affirmed its forthcoming opening to close his 1993 public lecture on the company;[4] similarly, Hayao Nakayama gave short acknowledgement to the plans in his 1994 new year party speech.[27] Mentions also started to appear in some press coverage,[28] as Nakayama revealed the full extents of his plans for the Amusement Theme Park concept - the facility following Osaka was to be the first full-scale example, setting a template for what Sega intended to follow across the world in at least 100 locations by 2000.[10] In the midst of this, high-level negotiations were formed by Sega with their aspirational enterprise, Disney, however these would fail, with the latter borrowing design cues from ATP development team AM5 for the DisneyQuest venture.[29]

Opening

Three months after the launch of an initial pilot Amusement Theme Park venue, Osaka ATC Galbo,[30] Yokohama Joypolis was opened to the public on 20 July 1994 after a press preview on the 18th.[31][32] Located on a 11,946m² plot of land in the Yamashita Park area of Yokohama, its site encompassed a main 8,250m² indoor theme park building ran by Sega, three additional facilities housing other businesses, and two visitor parking lots, making it the first full scale "ATP" location.[30] The park charged ¥500 and ¥300 entry fees through a card system, with individual attraction fees costing between ¥100 and ¥800;[33] this model was followed by subsequent Joypolis parks and retooled for the overseas Sega World locations.

At launch, the main building was largely dedicated to the park's seven major attractions located throughout most of its floor space, a carousel, and over 200 arcade machines,[34] many of which were stationed on and underneath a mezzanine sub-level between the first and second floors. Mad Bazooka, VR-1, and Rail Chase: The Ride made their public debuts at the park on opening day - due to their large sizes, the construction of all three and the complex's other facilities alongside each other would not have been feasible at any other location opened by Sega up to that point in time.

Alongside the three new attractions were a further four that had already debuted at large amusement venues in the previous months, including former Osaka ATC Galbo exclusives Astronomicon and Ghost Hunters. Supplementing these attractions in the main theme park building were an aforementioned roster of assorted video, carnival, and medal game arcade machines, a SegaSonic & Tails souvenir shop, and a Café Blanca restaurant. Two McDonalds franchises and a licenced bar counted as being part of the park were situated in three separate buildings, but could still be accessed on the same complex site.[35]

Initial reviews of Yokohama Joypolis appear to have been mixed to positive, with some reviewers claiming some of the touted technological feats of the attractions did not meet their expectations, though several praised VR-1.[36][37] After the launch, Sega took advantage of the venue's large size and capacity for organised events to hold numerous examples, including notable Virtua Fighter[38] and Sega Rally Championship[39] tournaments. These officially-held events were communicated through magazines handed out inside of the park, including SegaJack and Sega Magazine, and would become a key aspect of subsequent Joypolis centres. A Skate GSJ skateboarding meet was also held at the park in the following months.[40]

Operation

On October 8th, 1994[41], Yokohama Joypolis hosted the Japanese invitational tournament for the Sonic & Knuckles tournament Rock the Rock. Known as the World Championship Japan Tournament and attended by Yuji Naka himself[42], it was won by Hitoshi Kobayashi, who was promptly dressed in prison attire and flown to San Francisco, California for the next step of the tournament.[43]

Demise

Projected to make ¥3.6 billion and attract 1.2 million visitors in its first year of operation,[44] Yokohama Joypolis exceeded this, surpassing expectations by generating roughly ¥4 billion[45] and drawing in 1.75 million visitors.[46] However, the park's flagship status was soon superseded by Tokyo Joypolis in 1996, and the venue appears to have subsequently struggled to create similar numbers. One factor attributed to this was the fact that the park, situated away from the central districts of Yokohama, was a fifteen-minute walk from the nearest subway station, something later rectified in 2004.[47]

After a period of downtime, the park reopened under the new name of Joypolis H. Factory Yokohama on 25 July 1999,[48] with its ground floor level undergoing a partial refurbishment in the process. Its operations were now assisted by media personality and businessman Hiromi Kozono, who at the time was developing several sports-themed leisure centres in Japan.[49] A small number of new leisure attractions, such as go-kart tracks,[50] were added to support the main Sega-developed examples in place since 1994, which had since received software and theming updates.

Yokohama Joypolis closed permanently at the end of February 2001,[51] changing admission fees to ¥15 and ¥10 to scrap payments for its attractions and arcade machines in its final weeks.[52] The closure occurred in the midst of a restructuring at Sega, which also partially led to several other Joypolis venues as well as the overseas SegaWorld London and Sega World Sydney going defunct, a scrapping of the plans for 100 theme parks across the world, and the eventual discontinuation of the Amusement Theme Park concept, with managerial problems and cashflow issues cited.[53] Whilst some of its auxiliary facilities continued trading,[54] the space the main building formerly occupied subsequently became warehouse storage again, and its former grounds have more recently been redeveloped to house an apartment complex.[55]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 http://shmuplations.com/akiranagai/

- ↑ Billboard, "July 6, 1968" (US; 1968-07-06), page 44

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 File:SegaEnJoint JP Flyer.pdf

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 https://blog.goo.ne.jp/lemon6868/e/e813708f83b15c080885839bed6a7ad0 (Wayback Machine: 2021-10-10 18:53)

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Beep! MegaDrive, "October 1994" (JP; 1994-09-08), page 96

- ↑ Sega Saturn Magazine, "1996-09 (1996-06-14)" (JP; 1996-05-24), page 144

- ↑ Game Machine, "1991-11-01" (JP; 1991-11-01), page 1

- ↑ Leisure Line, "March 1996" (AU; 1996-xx-xx), page 51

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Game Machine, "1992-04-01" (JP; 1992-04-01), page 1

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Press release: 1993-07-04:Sega Takes Aim at Disney's World

- ↑ Famitsu, "1992-10-30" (JP; 1992-10-16), page 11

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Game Machine, "1992-11-15" (JP; 1992-11-15), page 16

- ↑ Game Machine, "1992-11-15" (JP; 1992-11-15), page 10

- ↑ Game Machine, "1992-11-01" (JP; 1992-11-01), page 11

- ↑ Beep! MegaDrive, "July 1993" (JP; 1993-06-08), page 34

- ↑ Game Machine, "1993-06-15" (JP; 1993-06-15), page 8

- ↑ https://koushihaken.jp/trainer/profile/507 (Wayback Machine: 2021-04-10 14:30)

- ↑ https://astamuse.com/ja/patent/published/person/5433477?queryYear=1994 (Wayback Machine: 2021-07-01 19:25)

- ↑ https://astamuse.com/ja/patent/published/person/6476097?queryYear=1996 (Wayback Machine: 2021-07-10 16:10)

- ↑ http://backup.segakore.fr/hitmaker/game/SOUND/SITE/member02.html (Wayback Machine: 2020-12-13 12:13)

- ↑ https://soundcloud.com/mandalazu/independence (archive.today)

- ↑ http://sound.jp/namiki/works/index.html#5 (Wayback Machine: 2005-01-09 04:02)

- ↑ @Hiro_H10th on Twitter (Wayback Machine: 2021-06-28 23:31)

- ↑ https://media.vgm.io/albums/86/4768/4768-1191149488.jpg (Wayback Machine: 2021-06-03 03:08)

- ↑ https://sbtransr02.wixsite.com/kazuhiko-nagai/my-works-1 (Wayback Machine: 2021-04-10 08:56)

- ↑ https://www.redbull.com/jp-ja/game-producer-mie-kumagai (Wayback Machine: 2021-07-11 20:12)

- ↑ https://mdshock.com/2020/06/16/sega-president-hayao-nakayamas-new-year-speech-1994/ (Wayback Machine: 2020-06-17 11:44)

- ↑ Press release: 1994-02-21:Sega!

- ↑ https://www.vrfocus.com/2017/07/the-virtual-arena-the-virtual-theme-park-part-1/ (Wayback Machine: 2021-01-19 12:56)

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 Game Machine, "1994-09-01" (JP; 1994-09-01), page 14

- ↑ Beep! MegaDrive, "August 1994" (JP; 1994-07-08), page 31

- ↑ Game Machine, "1994-08-15" (JP; 1994-08-15), page 1

- ↑ http://www.sega.co.jp/sega/atp/yokohama/guide.html (Wayback Machine: 1997-02-15 21:02)

- ↑ http://www.sega.co.jp/sega/atp/yokohama/data.html (Wayback Machine: 1996-12-24 10:53)

- ↑ http://www.sega.co.jp/sega/atp/yokohama/data.html (Wayback Machine: 1996-12-24 10:53)

- ↑ https://archive.org/details/sim_japan-times_august-08-14-1994_34_32/page/n9

- ↑ https://www.vrfocus.com/2020/07/the-virtual-arena-blast-from-the-past-the-vr-1/ (Wayback Machine: 2021-02-27 06:54)

- ↑ File:VirtuaFighter2EternalBattle VHS JP Box.jpg

- ↑ File:Yokohama Sega Rally Time Attack Festival.jpg

- ↑ https://www.flickr.com/photos/gijon/albums/72057594101098549

- ↑ Sega Visions, "December/January 1994/1995" (US; 1994-xx-xx), page 6

- ↑ File:RocktheRock YokohamaJoypolis YujiNaka.png

- ↑ File:MTV'SRocktheRockSonic&Knuckles1994 US Video.mp4

- ↑ Press release: 1994-08-15:Shisetsu-nai Inshoku Tenpo Shirīzu 'Joiporisu' 120 Man Hito o Shūkyaku e

- ↑ https://archive.org/details/contemporarybusi00boon/page/184

- ↑ File:Segaworld Trocadero '96 Promo Video.mp4

- ↑ http://www.sega.co.jp/sega/atp/yokohama/access.html (Wayback Machine: 1996-12-24 10:53)

- ↑ http://www.sega.co.jp/sega/atp/news/news994/jpnews990725.html (Wayback Machine: 2000-04-10 21:21)

- ↑ Dreamcast Magazine, "1999-25 (1999-08-13,20)" (JP; 1999-07-30), page 7

- ↑ http://www.sega.co.jp/sega/atp/news/news2000/jpnews0308_2.html (Wayback Machine: 2001-02-10 03:45)

- ↑ http://www.sega.co.jp/sega/atp/yokohama/home.html (Wayback Machine: 2001-02-11 15:34)

- ↑ http://www.sega.co.jp/sega/atp/news/news2001/jpnews0208.html (Wayback Machine: 2001-06-29 22:24)

- ↑ https://www.vrfocus.com/2020/07/the-virtual-arena-blast-from-the-past-the-vr-1/

- ↑ http://www.sega.co.jp/sega/atp/yokohama/home.html (Wayback Machine: 2001-06-29 22:24)

- ↑ https://www.google.com/maps/place/1-ch%C5%8Dme-14-18+Shinyamashita,+Naka+Ward,+Yokohama,+Kanagawa+231-0801,+Japan/@35.4409022,139.6562886,3a,75y,50.99h,90t